[ad_1]

WASHINGTON — President Biden plans to use the bipartisan debt limit deal to pivot back to his shadow reelection campaign, pointing to the achievement to burnish his image with voters as a consensus–builder who’s making strides on his promise to unite the country, advisers tell NBC News.

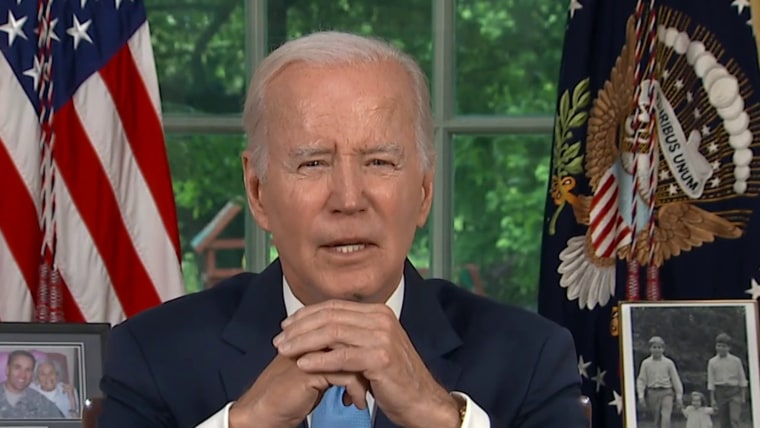

Biden signaled as much in his first Oval Office address Friday, which he began by recalling how skeptics, even in his own party, doubted he could work successfully with Republicans. The budget deal was just one of 350 bipartisan laws he has signed, he noted.

“I know bipartisanship is hard and unity is hard, but we can never stop trying, because in moments like this one — the ones we just faced, where the American economy and the world economy is at risk of collapsing — there is no other way,” he said.

The early phase of Biden’s 2024 campaign aims to showcase him as a drama-free leader who has defied expectations in working across the aisle. On Friday, Biden and first lady Jill Biden will travel to North Carolina to discuss worker training programs in his “Investing in America” agenda, the White House says.

It’s part of Biden’s “return to his previously scheduled programming,” a senior Biden adviser put it. His plan is to pivot from a month that was consumed by the debt standoff in Washington back to talking directly with Americans about his economic agenda, particularly legislation he has signed to fund infrastructure projects and revive domestic manufacturing, as well as outline how he envisions building on those efforts, aides said.

The bipartisan deal Biden signed over the weekend raises the debt limit and reduces federal spending.

The weeks ahead will not be a victory lap on the debt limit deal, aides said. After all, some Democrats strongly oppose several provisions in the legislation, which they view as succumbing to a “hostage-taking” strategy Biden had vowed not to take part in.

The White House counters that Biden was able to protect key legislative initiatives and limit proposed spending cuts as part of the negotiations. But for the White House, the biggest victory may have been something that wasn’t in the text of the bill.

“Clearly the fact that he is able to put together bipartisan approaches to solve problems in this country is a huge strong point for him that we do talk about and will continue to talk about,” a Biden adviser said. At the same time, the adviser cautioned, “this is a bipartisan bill. Campaigns are about contrasts.”

One of the contrasts Biden has sought to make as he campaigns for re-election, and that his advisers believe will be effective with voters, is between a president focused on doing his job and a growing, infighting Republican presidential field that continues to be largely shaped by former President Donald Trump.

A talking points memo Biden’s campaign distributed to key surrogates Friday argued that he was providing “strong and steady leadership after four years of chaos and dysfunction” and that his “wisdom and experience are why he was able to negotiate a deal that protects his administration’s key priorities and historic accomplishments.”

Biden’s re-election campaign was just days old when his treasury secretary warned that the U.S. was weeks away from running out of money to pay its bills. That triggered weeks of ominous economic warnings and fresh reminders of the deep divides in Washington, which Biden himself had acknowledged this year had been harder to repair than he’d hoped.

But the agreement Biden reached with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., which was quickly and resoundingly voted through in bipartisan votes in the House and the Senate, sent a Biden team that had been sharply criticized for ceding the messaging war to the GOP into overdrive to claim credit for what it cast as a major win.

Another Biden adviser said that even with some prominent Democrats opposing the debt deal, the overwhelming majority of House and Senate Democrats supported it, ensuring it made it to his desk.

Rep. Ann McLane Kuster, D-N.H., the chair of the center-left New Democratic Coalition, described part of her call with Biden last week as a “pat on the back for the process working” and said a “pragmatic solution prevailed.” She cast Biden’s style as “governing from the middle out,” pointing to how many swing district members in her coalition endorsed the compromise.

But she also said Biden showed he would fight for his priorities, and she credited him with ensuring changes to Social Security and Medicare were off the table.

Even as advisers tout the bipartisan breakthrough, Biden will continue to highlight the contrasts between the parties that will shape the 2024 campaign. In his Oval Office address Friday, he said he would continue to push for new taxes on the richest Americans, for instance.

“Republicans may not like it, but I’m going to make sure the wealthy pay their fair share,” he said.

While Biden will be able to leave Washington more often in the coming weeks than he was able to during the debt standoff, the events will continue to be considered official, rather than campaign events.

Biden’s campaign organization is still slowly taking shape. But aides are looking to highlight other key issues this summer that they believe would drive turnout among core voting constituencies, including, for instance, a major messaging effort around the first anniversary of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade on June 24.

Advisers have said they expect abortion will be an even bigger voting issue than it was in the 2022 midterm elections, when Democrats defied expectations by limiting losses in the House and even gaining a Senate seat. Biden will visit North Carolina, a battleground he came within 75,000 votes of flipping in 2020, just weeks after the GOP legislature overrode the Democratic governor’s veto of a law banning most abortions after 12 weeks.

Biden’s team also expects him to headline more fundraisers, especially until the end of the quarterly fundraising reporting period on June 30. That deadline will offer the first look at his campaign war chest.

Biden advisers continue to believe that Americans — or at least the key voting groups that they say powered his victory in 2020 — still dread the prospect of a long presidential campaign, especially a potential rematch with former President Donald Trump. Plans for more traditional campaign events are still months away, following the model of former President Barack Obama’s re-election campaign, in which Obama didn’t hold his first rally until May 2012.

[ad_2]

Source link