[ad_1]

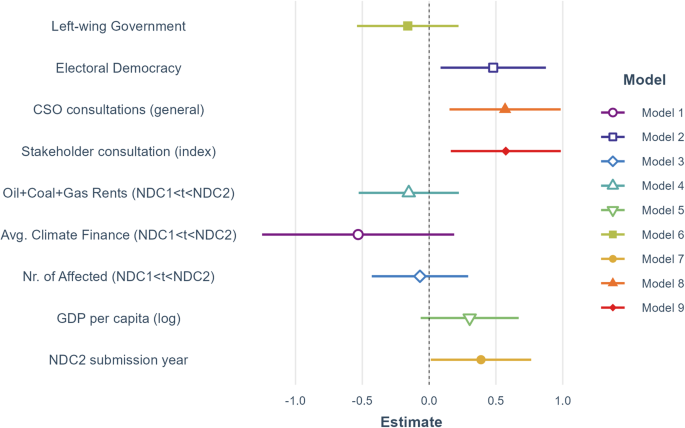

Figure 1 shows the results of the quantitative models for all political, economic, and structural factors included. Separate models are presented in Supplementary Table 1. First, we investigate the role of political institutions. Electoral democracy from the University of Gothenburg’s Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) database has a statistically positive relationship with the enhanced NDC targets at the 0.05 level (Fig. 1 and Table 1), meaning that countries with more democratic political institutions are more likely to enhance their NDCs. In models (2) and (3) of Table 1, we can also see that this relationship is independent of the level of economic development (GDP per capita) and the year in which the updated or revised NDC was submitted. In model (3), the least democratic countries (i.e., Qatar and Saudi Arabia, with an electoral democracy score of ~0.08) are ~34% likely to enhance the emission targets in updated or revised NDCs. Countries ranked low on the electoral democracy index (~0.5), such as Albania and Kenya, have a ~54% probability of enhancing their NDC mitigation pledges. Lower-ranked democracies (electoral democracy score ~0.75), such as South Africa, are 65% likely to improve on their initial NDC emissions, while highly democratic countries (i.e., electoral democracy score ~0.9 on the level of New Zealand and the United States) are 71% likely to enhance their pledge. However, partisanship was not statistically significant (We also test corruption in Supplementary Fig. 3).

The dependent variable is the dichotomous enhancement of the updated NDC (reduced total GHG emission estimate by 2030). Fossil fuel rents (oil+coal+gas), receipt of climate finance, and the number of people affected by climate hazards are taken as an average value between the submission of the first and the updated/revised NDC for each country. All other variables are measured from the year of the submission of the updated NDC (NDC2). Point estimates are coefficients from individual bivariate logistic regression models and are presented in terms of logged odds (the logarithm of the ratio of probabilities). Horizontal lines are uncorrected 95% confidence intervals.

We construct a new “CSO consultation index” that merges two pre-existing indicators into a single variable, namely: (1) Climate Watch’s indicator of whether stakeholder consultations were mentioned in the NDC; and (2) V-Dem’s CSO consultation indicator based on an expert survey28 (see Methods for a justification). In Table 2, we analyse the role of civil society consultation and find that countries where CSOs are commonly consulted, were more likely to enhance their NDCs. Countries that rank low on our CSO consultation index, such as North Korea (−1.96) and Nicaragua (−1.85), have a ~27% probability of enhancing their NDC pledges. Meanwhile, medium-ranked countries of our CSO consultation index, such as Paraguay (0.003) and Jordan (~0.1), which mention stakeholder consultations but rank relatively low on V-Dem’s CSO consultation indicator, are ~54% likely to enhance their NDC. Countries that score the highest (2.4) on the CSO consultation index, such as the United States and Switzerland, which mention stakeholder consultations as part of their NDC update and rank high on V-Dem’s CSO consultation indicator, are 71% likely to enhance their pledge.

The estimates for the economic and structural factors were statistically indistinguishable from zero. This supports the null hypothesis that fossil fuel rents, the receipt of climate finance, the number of people affected by climate hazards, and national income (GDP per capita) do not affect the enhancement of NDCs. While the aforementioned factors do not appear to matter for change in ambition (i.e., enhancement of NDCs), they may well influence static levels of climate ambition. For instance, although prior research has shown the adverse effect of fossil fuel rents on initial NDC targets, we find a negative but not statistically significant role for NDC enhancement7. Hence, fossil fuel rents do not seem to restrict NDC enhancement—at least not for the first round of updates and revisions. This may be the case because countries with substantial fossil fuel rents already exhibit overall lower baseline commitment to climate action—ceteris paribus—in their initial NDCs. GDP per capita, taken on its own, exhorts a positive but statistically insignificant effect on NDC enhancement.

We also analyse the individual effect of the submission year (2019–2021) of the updated NDC on enhancement (Fig. 1). The result is positive and statistically significant, meaning that the later the NDC update was submitted, the more likely parties were to enhance their NDCs. This result may be due to increased awareness of climate change due to the climate movement or better access to scientific knowledge, such as improved global and national 2030 emission trajectories. The positive role of improving scientific knowledge has also been shown in the case of the Montreal Protocol29. In addition, this finding supports the performance of the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet mechanism”30. This lends credibility to the general expectation that governments are inspired by the positive examples of prior NDCs and tend to continually improve their targets.

Case studies

We complement the large-n study with illustrative case studies, which expand on the mechanisms behind political institutions, the economy, and structural context31. When conducting qualitative country case studies, it is crucial to be mindful of the danger of selection bias and strive for a representative sample of cases. We strategically choose two cases that display variation in explanatory variables, such as government ideology, types of democratic institutions and public consultation, receipt of climate finance, fossil fuel production, and climate hazards (see Methods)32. This is to ensure we can make more confident inferences about the range of variation in the overall sample, as opposed to random selection, which is prone to bias with small sample sizes. Both countries are important substantively as major economies or significant emitters of GHGs and members of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) group, with similar levels of economic development.

Brazil

Brazil submitted the first NDC update during the Jair Bolsonaro government in December 2020. The updated NDC reaffirms the target of the initial pledge—to unconditionally decrease GHG emissions by 43% in 2030 (Table 2). The target was significantly less ambitious in the updated NDC since the 2005 baseline GHG emission level was raised ex-post to allow for higher emissions33. The updated NDC also “considers achieving carbon neutrality in 2060” and may even consider “a more ambitious long-term objective in the future, having as a time horizon, for instance, the year 2050”. However, very little information is provided about the measures to achieve it. The development of both the first and the updated NDC was entrusted to the Ministry of Environment, while the Ministry of Mines and Energy, Foreign Affairs, and the Office of the Chief of Staff of the Presidency were involved as well (interviewees #4 and #6).

The role of political institutions and the ideology of the President have been crucial for Brazil’s climate action. Climate change has been a thorny political topic in previous years34. Bolsonaro promised during his election campaign to withdraw Brazil from the 2015 Paris Agreement and open up the Amazon to increased deforestation35. While the government did not pull out from the Paris Agreement, the hostility of his administration to further climate action has been clear as it abolished the Secretariat for Climate Change and Forests, the agency responsible for action on climate change (interviewee #5).

According to interviewees, the 2021 updated NDC was developed behind closed doors without the explicit involvement of the scientific community and civil society (interviewees #1 and #5). The updated NDC was developed in an opaque manner, as the government restricted and underfunded the Brazilian Forum on Climate Change for stakeholder involvement. While the stakeholder consultations of the Brazilian Forum on Climate Change played a key role in informing the initial NDC, members of the Forum were not consulted for the updated NDC36. Overall, the decline in transparency in the NDC development process is consistent with general democratic backsliding during Bolsonaro’s tenure37. Hence, due to Bolsonaro’s absence of political determination to tackle climate change, combined with the exclusion of civil society and academia, the updated NDC did not enhance the GHG emission target of the first NDC. A lack of transparency and engagement with stakeholders allowed the government to submit a non-enhanced NDC with not even inconsequentially stronger GHG emission targets than the first NDC. Interviewee #1, who was involved in the first NDC development process that consulted CSOs, noted that stakeholder consultations could tilt the conversation to greater ambition due to greater national ownership.

Economic and structural factors did not appear to play a major role in the lack of enhancement of Brazil’s NDC update. With regard to fossil fuel dependence, although Brazil has oil reserves, it generates electricity mainly from hydropower (66%), natural gas, and wind38. According to interviewees, the most contentious mitigation issue during the NDC development process pertained to agriculture and deforestation (interviewees #2 and #4), given that land use, land-use change, and forestry and agriculture are two of the biggest sources of CO2 emissions in Brazil (66% in 2020)39. The bancada ruralista—a cross-party political caucus of federal deputies and senators who promote the interests of agribusinesses in congress—gained influence under Bolsonaro’s administration (interviewee #3). Also, Brazil is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as wildfires, temperature changes, and sea-level rise40,41. Nevertheless, although our Brazilian interviewees commented on the impacts of recent extreme weather events, they did not think the threat of climate change had played a role in the development of the NDCs.

Based on the document analysis and expert interviews, we find that one of the key changes was the obstruction of meaningful stakeholder consultation in the development process of the updated NDC compared to the initial NDC. The lack of stakeholder engagement was politically driven by the ideological change in government and represents a strategic decision since Bolsonaro’s administration was aware that more transparent engagement processes could have led to more public scrutiny and potential pressure from both local and international CSOs. Non-enhancement did not appear to be significantly affected by other economic and structural factors.

South Africa

South Africa submitted its updated NDC in September 2021, during the Presidency of Cyril Ramaphosa. The updated South African NDC set a more ambitious GHG target than the initial NDC by the Jacob Zuma administration in November 2016 (interviewees #7 and #8). The upper end of the target range for the year 2030 was reduced by 32%, and the lower range by 12% compared to the initial NDC (398–614 MtCO2eq by 2030) (Table 2). The development of both the initial and updated NDC was led by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, along with the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy and the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). The process involved technical analysis, consultation within government, broader stakeholders, provincial public stakeholder workshops, and finalisation in government and cabinet42,43.

In terms of political factors, climate change has not been a major electoral issue in South Africa. Rather, climate policy has been the result of deliberations within African National Congress party leadership, bureaucracy, and key stakeholders (interviewees #7–#9)44. However, the development of the updated NDC was more open to stakeholders than the development of the initial NDC (interviewee #11). In February 2021, Ramaphosa established the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC), which brought together 22 commissioners from government, business organisations, civil society, organised labour, and the scientific community to review the draft of the NDC update42,43. The PCC consultations played a key role in shifting the balance in favour of target enhancement compared to more sceptical government institutions, such as DIRCO and the Department of Trade and Industry (interviewees #7–#9)45.

Economic factors played a significant role during stakeholder consultations amid concerns about unemployment and economic decline as South Africa’s economy contracted by 6.4% in 202045,46. Labour organisations and big emitters opposed the closure of coal-fired power plants (interviewee #8). Particularly, mining and metalworkers’ unions were unwilling to team up with environmental organisations47. The Congress of South African Trade Unions has been reluctantly supportive of the energy transition out of concern over substantial job losses adding to the already high unemployment48,49 and supported the emphasis on a just transition, which was fully integrated into the NDC update (interviewees #8 and #10).

Historically, climate action has been impeded by South Africa’s high dependence on coal-fired power through the state-owned company Eskom, which is a central political actor along with the oil company Sasol50. However, Eskom has been immersed in a crisis due to spiralling prices and unreliability, while the cost of renewable energy has been falling51. Cheap domestic solar energy has rendered it a competitive alternative to coal and a potential solution to the crisis48. Stakeholders part of the PCC agreed about reducing overreliance on fossil fuels but disagreed about the specific measures and targets. All interviewees noted that by the time of the NDC update, the stance of the big emitters had shifted from obstruction to restrained collaboration, which was supported by fundamental changes in the cost of renewable energy technology (interviewees #7 and #9)44. Furthermore, the enhanced targets of the NDC were regarded as helpful for attracting more international climate finance (interviewee #10), although it was felt that further international financing was needed to achieve the climate targets, according to a business representative (interviewee #9).

Based on the presented evidence, we find that the main changes that mattered for the enhancement of the updated NDC target were political and institutional. Interviewees note that the PCC consultations played a key role in the enhancement of NDC targets by counterbalancing more conservative government departments. Transparent stakeholder engagement helped to inform the government of feasible climate targets, despite a challenging domestic and international economic landscape. According to the interviews, rampant disruptions in energy production have reduced confidence in the state-owned coal power producer Eskom. These trends were boosted by cost-effective and innovative renewable energy opportunities, such as the global decline in the price of solar energy.

[ad_2]

Source link