[ad_1]

Eurozone economists who have spent the past week dusting off their debt-sustainability models for Italy are feeling a slight sense of déjà vu. “All of a sudden, everyone has to have an opinion on Italian debt yields,” said Gilles Moec, chief economist at French insurer Axa. “It reminds me of 2012.”

In an echo of the eurozone debt crisis that erupted 10 years ago, the European Central Bank said on Wednesday it was again preparing to launch a new bond-buying scheme to contain a sovereign debt sell-off that has hit more vulnerable countries such as Italy much harder than more stable ones such as Germany.

However, there are important differences between now and then — when the ECB slashed interest rates and started buying huge amounts of bonds to tame a debt crisis that threatened to tear the eurozone apart.

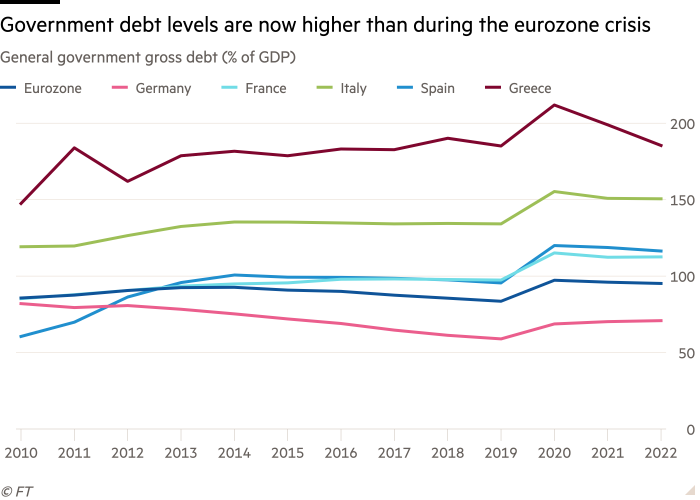

Some of these differences make today’s situation more worrying, such as the much higher debt levels of many eurozone countries, driven up by the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Italy’s government debt is above 150 per cent of gross domestic product — up from 127 per cent a decade ago — while Greece’s debt has risen even further from 162 per cent of GDP in 2012 to 185 per cent last year.

But other factors point in a more positive direction. One is that Europe’s banks are now more a source of strength than weakness. Dozens of undercapitalised lenders had to be bailed out during the 2012 crisis. Since then, most have strengthened their balance sheets, as shown by their resilience despite the deep recession caused by the pandemic.

An equally important change is the EU’s creation of a common fiscal instrument. An €800bn recovery fund set up in 2021 is supporting countries hit hardest by the pandemic with grants and cheap loans.

The recovery fund meant the ECB was no longer the “only game in town”, as had often been the case in previous crisis periods, its president Christine Lagarde said on Wednesday.

Francesco Giavazzi, a senior economic adviser to Italy’s prime minister Mario Draghi, cited the new EU fund as a big reason why he felt investors were being overly pessimistic about his country’s prospects. Those prospects had, he said, been transformed from a decade ago — even if the country’s debts were now much higher.

“What really matters for investors is not the level of debt but the trend in the ratio of debt to GDP,” said Giavazzi. “A little debt rising fast is very worrisome; a large [debt-to-GDP ratio] that is falling is less worrisome.”

Italy’s €200bn EU-funded Covid-19 recovery programme is providing support worth 12.5 per cent of GDP over five years — or 2.5 per cent of GDP in additional demand each year. The scheme requires Italy to undertake wide-ranging reforms to boost competitiveness and efficiency that should raise the country’s long-term growth trajectory.

“The plan helps us at least for the next five years,” said Giavazzi. “It will help in not going back to growth of 1 per cent.”

Though the Ukraine war has hit Italy’s economy hard, Giavazzi said output was still projected to expand by about 3 per cent this year, well above its long-term average of below 2 per cent.

In its most recent projections, Rome forecasted its debt-to-GDP ratio would fall to 147 per cent this year, down from 150.8 per cent last year and 155 per cent in 2020. Italy’s fiscal deficit is also due to drop from 6 per cent of GDP this year to 3.7 per cent next year, according to the IMF.

“The big difference between today and 10 years ago is that then the debt-to-GDP ratio was rising and the economy was falling,” said Giavazzi. “This time, the economy is rising and the debt-to-GDP is falling like a rock.”

The ECB now has more experience in dealing with crises too. Under the stewardship of Draghi, the central bank created a playbook for how to tackle the widening gulf in borrowing costs between member states. It has the potential to be quicker and more effective in its response to contain the risk of another bond market panic.

“We are in a better position to face this crisis from a European and ECB perspective,” said Lucrezia Reichlin, economics professor at London Business School and former head of research at the central bank. “Many taboos have been broken,” Reichlin added, alluding to the difficulties the central bank faced in convincing the political and economic elite in Germany and other northern member states to buy bonds.

A decade on, another big difference is that eurozone inflation is now at a record high of 8.1 per cent.

Inflation makes national debt levels look more manageable because they are measured against nominal GDP, which tends to be higher when price pressures are elevated. Governments also typically collect more tax when prices rise.

However, price pressures are a double-edged sword.

The ECB’s plans, announced on Wednesday, to potentially buy more bonds of weaker eurozone countries would, at first glance appear to contradict the pledge made last Thursday to tighten borrowing costs by raising rates and halting earlier asset-purchase programmes.

The difficulties in explaining this policy mix could weigh on the effectiveness of its strategy to dampen price growth, said analysts.

“In contrast to 2014, [the ECB’s] inflation-fighting credentials are now on the line,” said Anatoli Annenkov, senior European economist at Société Générale, adding that the eurozone’s rate-setters would need to “tread carefully”.

[ad_2]

Source link