[ad_1]

MEXICO CITY — Mariantonela Orellana spent nine days in the dangerous Darien Gap jungle in the Colombia-Panama border, and she described her nightmarish ordeal.

She crossed four rivers and nearly drowned; had a nervous breakdown, she said, because for hours she couldn’t find one of her children; saw corpses of other migrants rotting on the trails; and as if that weren’t enough, had to scare away some jaguars that began to stalk their makeshift camp in the thick jungle.

“You have to mentally prepare yourself and really want to forge ahead, because it’s very difficult to continue,” said Orellana, 35, who left the economic and political turmoil of her home country, Venezuela, in 2019. She first lived in Ecuador before embarking north toward the U.S.

“I’m here because of my daughters who told me, ‘Mom, you have to continue.’ That was what motivated me, but we went through hell, and we still haven’t arrived.”

The most recent official data from the International Organization for Migration states that nearly 250,000 migrants crossed the dangerous Darien jungle in 2022, a historic figure that far exceeds the 133,726 people who crossed in 2021 and the 8,594 in 2020.

Venezuelans like Orellana have become a constant presence in various capitals of the continent, as is the case in Mexico City, where public and private shelter operators are overwhelmed and many migrants sleep on the street — as was the case in front of the Venezuelan Embassy in the neighborhood of Polanco.

Due to this, the number of people arriving at the shelters greatly exceeds their capacities, like at Cafemin, where a staff of 15 to 20 people attends to the needs of 500 migrants, although its actual capacity is only 80 to 100 people.

Though the final destination for many Venezuelan migrants is the U.S., many have been turned away at the U.S. border through Title 42, the Covid-era measure that is still in place. Now back in Mexico, migrants wrestle with whether to try to stay in Mexico, keep trying to seek asylum in the U.S. or return to Venezuela.

“Many Venezuelans who made that long itinerary from South America to the United States and who were expelled to Mexico were left without resources because they had to pay the coyotes, and the corrupt authorities of some countries, so they decide to request protection here,” Andrés Ramírez Silva, general coordinator of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, (Comar), told Noticias Telemundo.

‘The American dream became a nightmare’

Orellana is part of a group of Venezuelans who are immersing themselves in a collective catharsis to help heal memories of their painful journey through borders and thousands of miles.

They’re participating in a production of William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” adapted by the Non Gratos theater company in Mexico City, which usually works with migrants and people who are displaced.

“This makes me able to continue,” Orellana said. “When I return to the shelter, I remember everything again.”

According to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, more than 150,000 Venezuelans entered U.S. territory through Mexico during the last fiscal year. According to Department of Homeland Security data, the flow of Venezuelan migrants to the U.S. increased by almost four times compared to the year prior.

Mexico was the world’s third most popular destination for asylum-seekers in 2021, after the U.S. and Germany, according to the United Nations.

Almost 13,000 Venezuelans requested political asylum in Mexico in the first 11 months of 2022, 39% more than the total for the prior two years. Mexican authorities approved 61% of asylum applications from January to November, including at least 90% of approvals for Hondurans and Venezuelans.

By contrast, the U.S. authorization rate was 46% in the fiscal year ending Sept. 30.

“The American dream became a nightmare for us, but we still want it,” said Angela Carolina Carvajal, a 41-year-old Venezuelan migrant who’s participating in the play. She said she felt she was “treated like garbage” in the U.S. once she crossed the border before being expelled, but she said she’s too afraid in Mexico and she was almost kidnapped. “I’m going to try to go up again, although we don’t have a sponsor or anyone to help us there, but God is great. And I want my children to have a better future, a better education and good food.”

The bitter return to the homeland

“I was crossing a large avenue, and I was carrying my child; I was very tired from walking all day, without resting, and a motorcycle ran over us and I was knocked unconscious, which is why I have a fracture in my right leg,” said Rosailys Lugo, 23, who was sleeping on the sidewalk in front of the Venezuelan Embassy in mid-December. “My son Luciano was in intensive care — his brain was inflamed.”

“Because of everything that happened to us, we decided to return to Venezuela, and we’re going to stay on the streets until we can take the government’s flights back to my country,” she said as she watched her son, who was sleeping wrapped in blankets on the cold concrete.

It’s estimated that a total of 2,060 migrants have returned to Venezuela as of December through the Plan Vuelta a la Patria (Back to the Homeland), a Venezuelan government program to facilitate the return of citizens to the country.

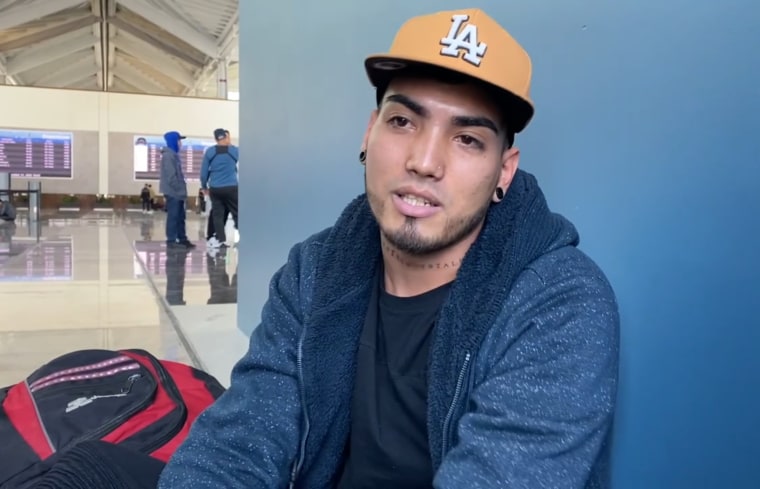

Johan Torres was waiting for a flight to return to Venezuela. Sitting on the shiny floor of Mexico’s new Felipe Angeles International Airport in November, he said there were two images of his treacherous journey north that he couldn’t get out of his head. The first was how a person who resisted a robbery in Mexico was killed with a machete; the other happened in the jungle, when he saw a man leave behind his young daughter, waist-deep in mud.

“He left her there, lying in the mud and crying. And I couldn’t do anything because I was dying of exhaustion. But I can’t forget that,” he said with tears in his eyes.

According to the Venezuelan government, more than 30,000 Venezuelans have returned to the country in the last four years. However, that figure pales in comparison to the more than 7.1 million Venezuelans who have left the country in recent years, according to United Nations data.

On the same day that Torres was waiting for his flight, Jefferson Ontiveros, 25, also wanted to take a return flight.

“I left Venezuela because the discrimination against the LGBT community is terrible; we are trampled on and attacked every day. We came looking for that dream of freedom to be able to have a future, but the circumstances were not favorable,” he said. “I leave with a wounded heart from all the abuses, the bribes I had to pay on the trip and the difficulties.”

By mid-December, Torres was already in Maturín, his hometown. He said that as soon as he got to his house, he fell into a state of exhaustion and he slept for five days. He said he still had nightmares of immigration officials speaking in English and Spanish, and it startles him.

“I hope to arrange my papers again and make plans, because, if given the opportunity, I’ll go again. I have to get a good job, and here that is almost impossible,” Torres said.

By the end of December, Ontiveros had gone to Venezuela, but he only stayed a few days, catching up with his relatives before leaving again, this time to Lima, Peru. He said jobs, transportation and other things were just too hard in Venezuela. In Caracas, “there are no opportunities.”

‘Justice came into my life’

Dec. 20 was a great day for Ángel Sucre. He got up early and tried to focus on his chores, but he kept looking at his phone. Finally, he received the call he had been waiting on for months: He heard from U.S. authorities that he had received asylum.

“I still can’t believe it. It was like my gift from baby Jesus,” he said in late December from his home in Kansas City, Missouri.

However, Sucre’s case is an exception; data from Syracuse University’s TRAC program shows that about 1.6 million asylum applications are pending in U.S. immigration courts and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, the largest number ever recorded.

“I arrived before the whole wave this year and I was a political prisoner in Venezuela, so my case is different. The truth is that after all the persecution I suffered in my country, justice came into my life,” he said.

Sucre has become an involuntary guide for dozens of Venezuelans who have taken to the roads of South America and are trying to cross into the U.S., despite tougher asylum policies that were recently implemented.

As of Oct. 12, Venezuelan applicants must possess a valid passport, have a financial sponsor within the United States, finance their own travel, pass a review, and not have been expelled from the U.S. in the last five years. In addition, they must not cross the borders of Panama, Mexico or into the U.S. without authorization. This program has a limit of 24,000 people.

“The main thing is that people do not lose faith and that they continue fighting for their goals, for their dreams and for their peace of mind. I know that many people must feel very bad right now, but they have to try to comply with everything legally,” said Sucre.

Meanwhile, Non Gratos continues to work in Mexico City with migrants. The staging of “The Tempest” allows those who have been displaced to immerse themselves in the spells of the sorcerer Prospero and his island while they re-create a work that Shakespeare wrote in 1611.

“The arts allows you to build a community with resilience and self-esteem,” said theater director Marco Guagnelli. “They also give many tools to be able to connect with emotions and memories that are often contained and don’t have the possibility of finding a space where they can be expressed.”

For Carvajal, the momentary oblivion provided by the play is a blessing. She said it allows her to continue dreaming of a good future for her family.

“Life changes us because we have all suffered and all have different stories. It’s as if we forget the world and we’re only here. We laugh, play and cry, but it is very beautiful,” she said. “Thank God this reminds me that I am alive.”

An earlier version of this story was first published in Noticias Telemundo.

[ad_2]

Source link