[ad_1]

Two separate viral mascara moments blew up on TikTok last week, prompting some to question whether “algospeak” — internet slang to get around harsh moderation guidelines — is as effective as users think.

On one side of the platform, the “mascara trend” featured people discussing previous sexual or romantic experiences they have had by using “mascara” as a code for penises or romantic partners. Elsewhere on the app, beauty enthusiasts were outraged by a seemingly misleading mascara advertisement from influencer Mikayla Nogueira. Meanwhile, people who were not pushed any of these videos before struggled to understand why others were getting so heated over a simple makeup product.

“The problem is that, with TikTok, even somebody that’s really really [online] might not get it because their FYP [For You Page] looks different,” said Nicole Holliday, an assistant professor of linguistics at Pomona College in Claremont, California.

Depending on what your algorithm feeds you, you may find yourself confused about what exactly people are talking about. Or, you may find yourself in a position similar to that of actor Julia Fox, inappropriately engaging with a video for which you have no context.

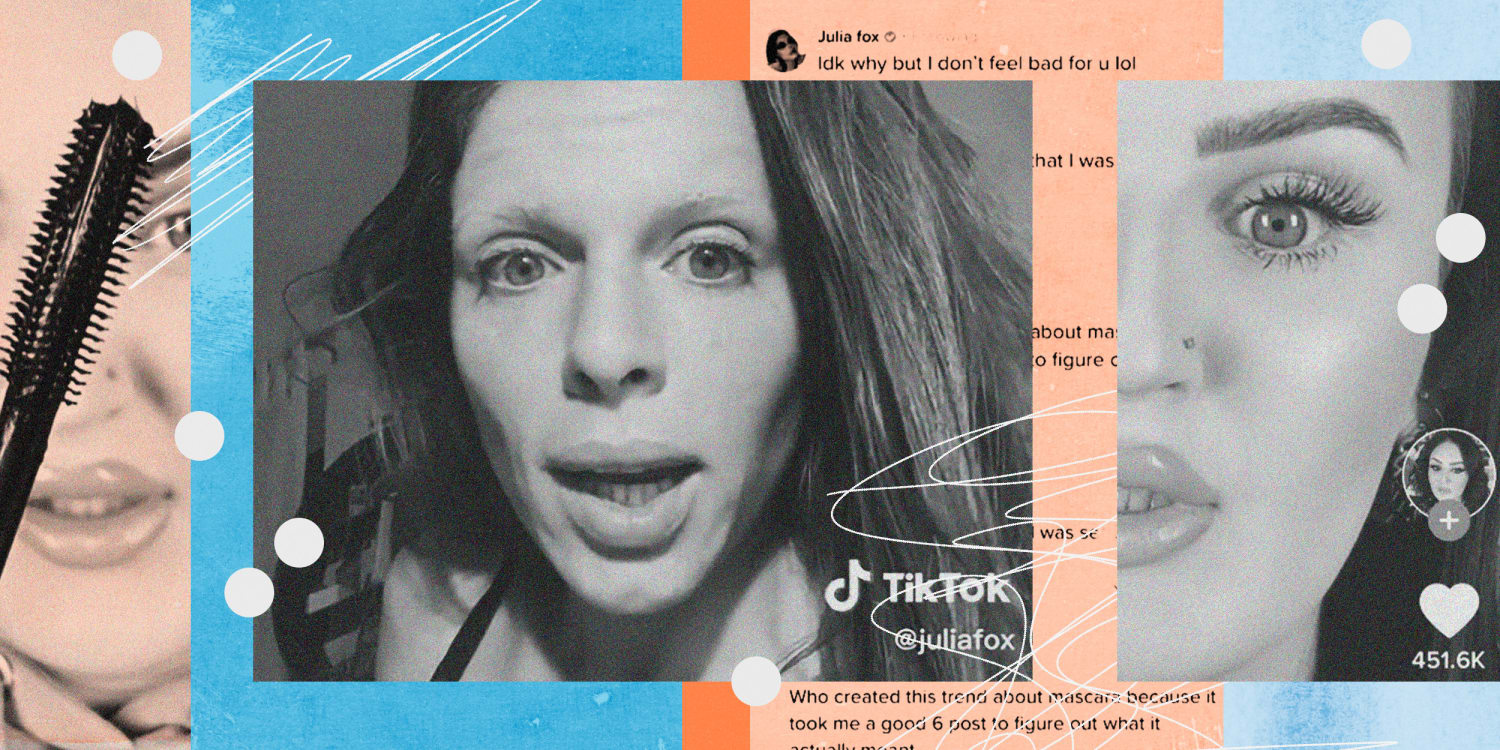

On Thursday, Fox apologized to a TikTok user after she left a comment on his video about his sexual assault, which featured the word “mascara” as code for his body.

“I gave this one girl mascara one time and it must’ve been so good that she decided her and her friend should both try it without my consent,” the TikTok user, Conor Whipple, wrote in the on-screen caption of his video.

“Idk why but I don’t feel bad for u lol,” Fox said in a now-deleted comment. After people started calling out Fox for discrediting a sexual assault survivor, she deleted her initial comment and apologized to Whipple, saying she didn’t know that “mascara” was code for something else.

“Hey babe I’m so sorry I really thought u were talking about mascara like as in make up. I’m sorry that happened to u,” she wrote.

Neither Whipple nor Fox immediately responded to requests for comment.

Whipple was participating in the “mascara trend,” which has encompassed a wide range of videos about sex, sexual assault and relationships. According to Know Your Meme, the trend started after a user posted about losing their “mascara” in a Jan. 12 TikTok. In the caption of the video, the user clarified that her video “isn’t about mascara” and Know Your Meme said the TikTok was actually about a vibrator.

The trend evolved from there, with people using “mascara” as an euphemism for penis size, beloved boyfriends, abusive partners, sex toys and more. On TikTok, users often find new ways to talk about sex, sexuality, violence, abuse, death and other disturbing topics in order to avoid getting censored by the app’s moderation system. These codes and euphemisms are often referred to as “algospeak” because they are used to game fickle algorithms, according to The Washington Post.

As a newer and smaller trend, not every user who came across a “mascara trend” video understood what the TikToks meant right away. And while the algorithm is hyperspecific to each user’s interests, it also has a tendency of dropping people into the middle of viral trends, drama and discourse without context.

Comments under various “mascara trend” posts reflected the mixed reception of the trend among viewers, with some catching on to the euphemism right away and others sharing their confusion. Holliday said that the “multiple meanings” within the “mascara trend” made it difficult to catch on as a slang term. With the threat of moderation, users on TikTok must also constantly innovate when it comes to euphemisms that refer to topics like sex.

“It seems to have popped up out of nowhere last week, but it’s part of a pattern of what we’re seeing with algospeak,” Holliday said. “It’s changing really, really fast because the whole point of algospeak is to avoid censorship. So, as soon as TikTok figures out what people are using as a code word, it gets banned, and then they have to move on to something else. Nobody can keep up with the life cycle of this slang because it’s moving too fast.”

Holliday said it’s “feasible” that Fox was unaware of the “mascara trend” in which Whipple was participating. She added that it’s an “unreasonable expectation for humans” to keep up with every new word that TikTok users introduce. Fox herself said in a TikTok Story on Thursday that she was not aware of the trend when she commented on Whipple’s post.

When news of Fox’s mascara comment reached Twitter, users were even more confused about which mascara drama people were discussing. This is because, amid Fox’s transgression, another mascara scandal was brewing within the beauty community on TikTok.

What is so difficult about TikTok is people are creating for an audience that might be really different than who actually sees it. And so, in that way, people have sort of lost control over meaning.

-Nicole Holliday, assistant professor of linguistics at Pomona College

Mikayla Nogueira, a popular beauty TikToker, was accused of lying about wearing false eyelashes in a sponsored post promoting the L’Oreal Telescopic Life mascara. In the post, she stitched another creator using the mascara and claimed the product “literally just changed my life” and “looks like false lashes.” When a viewer asked Nogueira if she was wearing false eyelashes in the promotion, she said, “Nooo, just three/four coats and my tight liner.”

Representatives for Nogueira and L’Oreal did not immediately respond to request for comment.

Nogueira’s ad was met with backlash and sparked a debate over authenticity in the influencer space. Viewers expressed their disappointment that she may have been dishonest with them. Veteran YouTube beauty gurus such as Alissa Ashley, Jeffree Star and Kathleen Lights also criticized Nogueira and expressed the importance of trust between creators and audiences.

“Stuff like this is why people do not trust influencers and it’s so upsetting,” Ashley said in a TikTok. “Little moments like this are why influencers as a whole get a bad wrap. More specifically, beauty influencers who do product reviews, who do sponsorships, that’s why people are always saying, ‘Oh, we can’t trust them.’”

With these two mascara discourses occurring simultaneously on TikTok, people were having a difficult time distinguishing what kind of “mascara” others were talking about. While some people questioned Fox’s prior knowledge about the “mascara trend,” others argued that the various discussions around mascara — literally and figuratively — made it difficult for anyone to understand what people were trying to communicate.

Holliday said that the meaning of words “only exists in context.” In the real world, when people talk to each other, they negotiate meaning within a conversation and are able to clarify when they feel like they’ve been misunderstood.

“What is so difficult about TikTok is people are creating for an audience that might be really different than who actually sees it,” she said. “And so in that way, people have sort of lost control over meaning.”

While the TikTok algorithm is good at pushing videos according to a person’s preferences, creators often share that their videos landed on the “wrong side of TikTok,” meaning the audience their video reached was not the intended audience of the post. This creates misunderstandings that can result in dogpiling or criticism from viewers outside of the creator’s target community. And when a video goes viral, the sheer volume of people in the comment section of the post can make it difficult for creators to go back and clarify what they mean if people misinterpret their posts.

“People have got to be more patient with each other about meaning and context,” Holliday said. “I hope that people start to be like, ‘This person doesn’t understand what this means because they’re 30 or they’re not chronically online or they’re just in a different community,’ rather than immediately blaming them for not getting it.”

[ad_2]

Source link