[ad_1]

Background

This report, produced by the Travel Health and International Health Regulations (IHR) team in the Clinical and Emerging Infections Directorate, UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), summarises case numbers of selected travel-associated infections reported in England, Wales and Northern Ireland between 2015 and 2022. Case numbers were previously reported through ECDC between 2015 and 2019 for chikungunya, cholera (Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 or O139), dengue, yellow fever and Zika. The data presented in this report supersedes any other case numbers previously reported.

Detailed information is included on the trends of chikungunya, cholera, dengue, leishmaniasis, rickettsial infections, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminth infections and Zika in 2022. An infection summary and key findings are provided for filariasis, Japanese encephalitis, trypanosomiasis and yellow fever. Data presented here is derived from a variety of sources and may be subject to limitations in completeness due to various factors, including underreporting.

Detailed annual reports are available elsewhere for

imported malaria cases in the UK and

travel-associated enteric fever cases in EWNI.

Data sources

Data for cases of chikungunya, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, rickettsial infections, yellow fever and Zika was obtained from the Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory (RIPL), UKHSA Porton. Case definitions used for these infections are as follows:

- confirmed: molecular detection (PCR, other molecular amplification test or sequencing) and/or positive virus isolation and/or seroconversion between acute and convalescent samples and/or 4-fold rise in antibody titre

- probable: IgM and IgG positive and compatible clinical syndrome

Data for confirmed cholera cases was obtained from the UKHSA Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU). A confirmed case is a person with Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 or O139 confirmed by the GBRU.

Data for cases of filariasis, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminth infections and trypanosomiasis was obtained from the UKHSA Second Generation Surveillance System (SGSS) (formerly LabBase2) (1). SGSS is a voluntary national surveillance database and a live laboratory reporting system; therefore, numbers may fluctuate, and travel and species information are limited. In addition, method of diagnosis is unavailable for most cases and therefore it is unknown whether they are diagnosed by serology, microscopy or other methods. Cases reported in SGSS are diagnosed by NHS or local independent laboratories and are defined as probable cases.

For all cases, specimen collection date was used where available to conduct analysis. In cases where this information was not available, laboratory receipt date was used. Case numbers presented in this report include both confirmed and probable cases, gathered from multiple sources, including confirmed cases from GBRU, probable cases from SGSS, and both confirmed and probable cases from RIPL.

Data for UK residents and UK overseas visitors was obtained using the International Passenger Survey (IPS) data provided to the Travel Health team by the Office of National Statistics (ONS). Further information and analysis for travel trends seen in 2022 were obtained from the ONS website (2).

World regions of travel were assigned based on the United Nations world region classifications (3).

Changes in travel to and from the UK in 2022

Data on travel to and from the UK was obtained from the Office of National Statistics International Passenger Survey. In 2022, UK residents made 71.0 million visits abroad, a 4-fold increase compared to 2021 (19.1 million). There were 31.2 million visits made by overseas residents to the UK, a 5-fold increase compared to 2021 (6.4 million). These increases can be attributed to the easing of COVID-19 travel restrictions at the end of 2021. However, travel to and from the UK in 2022 remained below pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels in 2019 (Figure 1) (4).

For both UK visits abroad and overseas visits to the UK in 2022, seasonal travel trends returned to pre-COVID-19 travel patterns, with most travel in occurring during the summer and a peak in August. The most popular reasons for travel for UK residents in 2022 were holidays, with 45.6 million visits, followed by visiting friends and relatives (19.0 million) and business travel (4.8 million). The top 5 most visited countries were Spain, France, Italy, Greece and Portugal. Holiday travel was also the most popular reason for overseas residents visiting the UK in 2022, followed by visiting friends and relatives and business travel. This is a change compared to 2021 when visiting friends and relatives was the most popular reason for travel to the UK. Residents of the USA, France, Republic of Ireland, Germany and Spain represented the highest numbers of overseas residents visiting the UK (2).

Figure 1. Visits to and from the UK from 2013 to 2022

Travel-associated infections 2015 to 2022

Table 1. Travel-associated infections in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (EWNI): 2015 to 2022

| Disease (Organism)* | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chikungunya | 101 | 155 | 90 | 59 | 100 | 33 | 17 | 31 |

| Cholera (Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 or O139) | 15 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Dengue | 424 | 464 | 441 | 416 | 790 | 91 | 97 | 448 |

| Filariasis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 17 |

| Japanese encephalitis | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Leishmaniasis | 13 | 17 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 36 | 24 | 51 |

| Rickettsial infections | 51 | 33 | 42 | 39 | 39 | 12 | 4 | 31 |

| Schistosomiasis | 43 | 42 | 38 | 65 | 48 | 40 | 66 | 123 |

| Soil-transmitted** helminth infections | 63 | 61 | 51 | 58 | 142 | 93 | 171 | 262 |

| Trypanosomiasis | 1 | 4 | 1 | – | 2 | – | 2 | 1 |

| Yellow fever | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Zika | 4 | 275 | 21 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

*Only includes confirmed and probable cases

**This includes Trichuris spp., Ascaris spp., Strongyloides spp., Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale

Table 1 presents reported travel-associated infections in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland from 2015 to 2022. Dengue remains the most frequently reported infection, with the highest number of cases (790 cases) reported in 2019. While most of these infections have returned to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels, case numbers for others including cholera, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, filariasis and leishmaniasis have exceeded these. The reasons for these trends are not always clear and could reflect changes in ascertainment, testing patterns as well as the burden of disease. In addition, data for schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, filariasis and leishmaniasis comes from SGSS and is subject to limitations, therefore these trends should be interpreted with caution.

Chikungunya

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne infection transmitted by the bite of an infected female Aedes mosquito and is caused by a virus from the Flaviviridae family. It is characterised by a sudden onset of fever usually accompanied by joint pain (arthralgia); however, symptoms vary in severity. Serious complications are uncommon, but, rarely, in older people the disease can contribute to the cause of death, particularly if there is other underlying illness. Chikungunya mainly occurs in Africa, Asia and specifically in Southern Asia, although there have been cases reported in parts of Europe and North America (5).

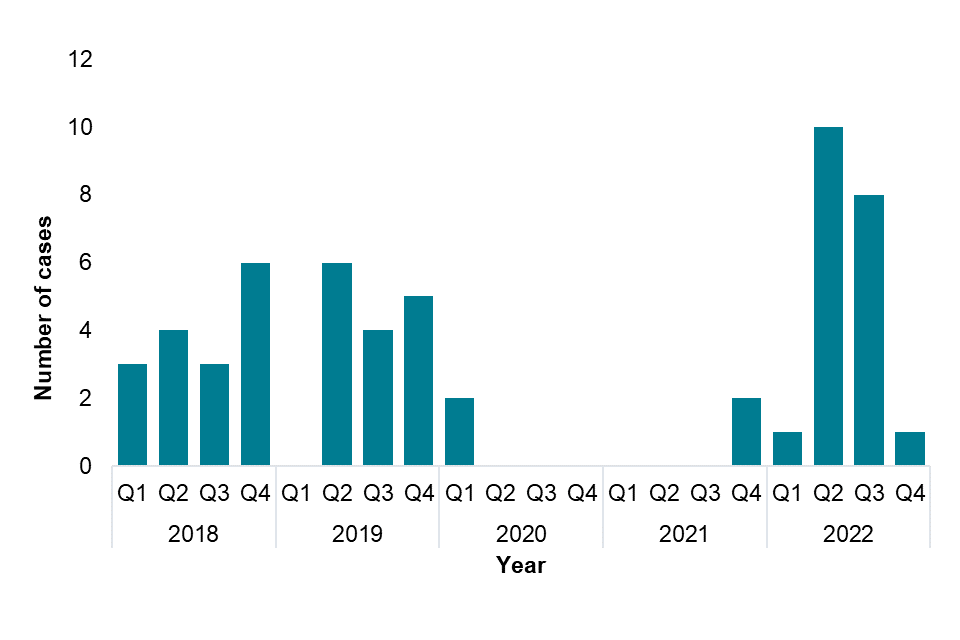

In EWNI there were 31 chikungunya cases reported in 2022, all of these from England. Of these, 11 (35%) were confirmed cases and 20 (65%) were probable cases. This represents an 82% increase compared to 2021 (n=17) but remains lower than the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 101 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019. Case numbers were low in the first three quarters of 2022 (n=3, n=3, n=6) and the majority of cases (n=19) were diagnosed in the fourth quarter (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cases of chikungunya by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

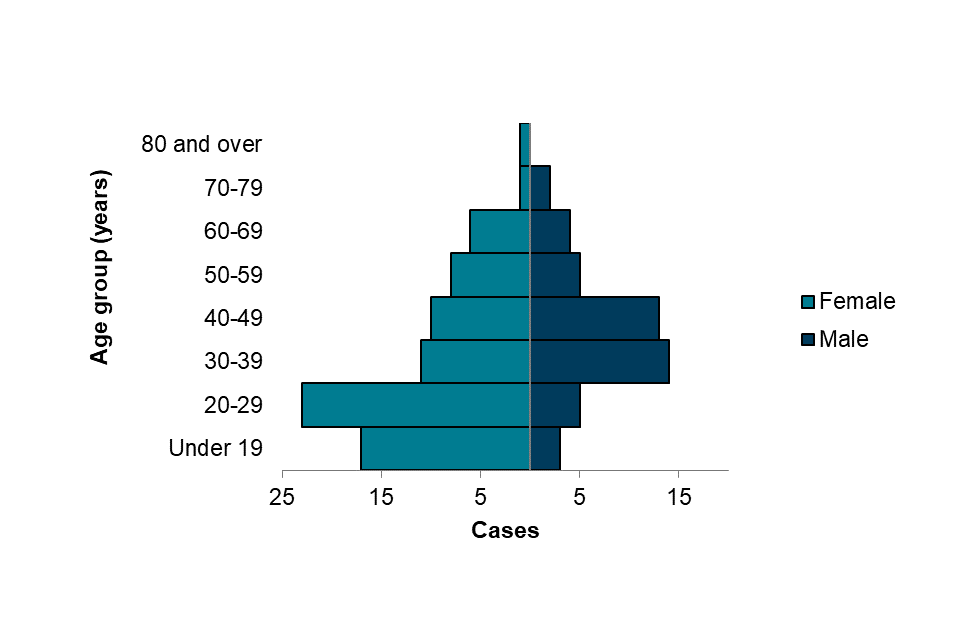

In 2022, 11 cases (36%) were female (aged 25 to 82 years, median=44) and 19 (61%) were male (aged 26 to 70, median=49, Figure 3). Sex was not recorded for 1 case.

Figure 3. Cases of chikungunya by age group and sex, 2022 (n=30)

In 2022, travel history was known for 30 out of 31 cases, with the majority of these reporting travel to Southern Asia (15, 50%) and Western Africa (8 cases, 27%), similar to 2021 (Table 2). The most frequently reported country of travel was India (15), followed by Ghana (3) and Nigeria (3). Cases who travelled to India reported travelling to a number of regions including Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and West Bengal. India reported a 20% increase in chikungunya cases (confirmed and suspected) in 2022 compared to 2021 (6), including in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal where EWNI cases reported travelling to.

Table 2. Cases of chikungunya by region of travel, 2022

| Region of travel | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Southern Asia | 15 |

| Western Africa | 8 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 4 |

| Eastern Africa | 2 |

| Middle Africa | 1 |

| Not stated | 1 |

| Total* | 31 |

*Some cases travelled to more than one region; all regions are included here so the total may be higher than the actual number of cases.

Cholera (Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 or O139)

Cholera is caused by infection of one of 2 serogroups of the Vibrio cholerae bacteria, serogroups O1 and O139.

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal disease caused by ingestion of contaminated food or water. A vaccine is available but is only recommended for some travellers. Cases of cholera may be asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, including acute, profuse watery diarrhoea (‘rice water stools’) and vomiting, leading to dehydration. Some infections may progress to severe disease, and in extreme cases may result in death if untreated (7). Cholera cases were reported in 35 countries in 2021 and the disease occurs mainly in Africa and Asia, but sporadic cases have also been reported in other regions (8).

Between 2015 and 2019 there were an average of 15 cases each year in EWNI, with a peak of 17 cases in 2018. There were 20 cholera cases reported in 2022, all of which were reported in England. This was a large increase compared to 2021 where 2 cases were reported. Case numbers were highest in the second and third quarters (n=10 and n=8) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cases of cholera by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

In 2022, 9 cases (45%) were female (aged 1 to 78 years, median=34) and 11 (55%) were male (aged 1 to 72 years, median=43) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Cases of cholera by age group and sex, 2022 (n=20)

In 2022, travel history was known for all cases, with the majority of these reporting travel to Southern Asia (17, 85%) (Table 3). The most frequently reported country of travel was Pakistan (10), followed by Bangladesh (4), India (2) and Iraq (2). The high number of cases reporting travel to Pakistan reflects ongoing floods and heavy rain reported in Pakistan in 2022 during the rainy season, which has led to increased cholera cases reported in flood affected regions (9). Since 2022, 30 countries across Africa, Asia and the Caribbean have reported cholera cases or outbreaks, with many countries reporting higher cholera case numbers and case fatality ratios (10).

Table 3. Cases of cholera by region of travel, 2022

| Region of travel | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Southern Asia | 17 |

| Western Asia | 2 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 1 |

| Total | 20 |

Dengue

Dengue is a mosquito-borne infection transmitted by the bite of an infected female Aedes mosquito. It is caused by a virus from the Flaviviridae family and has 4 main serotypes: DEN-1, 2, 3 and 4. Illness is characterised by an abrupt onset of fever often accompanied by severe headache and pain behind the eyes, muscle pain, joint pains, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and loss of appetite; however, symptoms can range from mild or non-existent to severe. Severe dengue is rare in travellers. Dengue is endemic in over 100 countries across Africa, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific, with sporadic cases occurring in some other countries in Europe (11).

In EWNI there were 448 dengue cases reported in 2022 (427 in England, 16 in Wales and 5 in Northern Ireland), of which 410 (92%) were confirmed cases and 38 (8%) were probable cases. This was a significant increase compared to the 97 cases reported in 2021, though it remains lower than the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 507 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019. Case numbers were low in the first 2 quarters of 2022 (n=36, n=54) and the majority of cases were diagnosed in quarters 3 and 4 with 174 and 184 cases respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Cases of dengue by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

In 2022, 189 cases (42%) were female (aged 2 to 85 years, median=37) and 259 (58%) were male (aged 3 to 90, median=37, Figure 7).

Figure 7. Cases of dengue by age group and sex, 2022 (n=448)

In 2022, travel history was known for 388 out of 448 cases (87%), with the majority of cases reporting travel to Southern Asia (248, 64%) and South-Eastern Asia (52, 13%) (Table 4). The most frequently reported countries of travel in Southern Asia were India (n=106), Pakistan (n=57) and Nepal (n=47). Many Southern Asian countries have reported a surge in dengue cases in 2022 compared to 2021, including India which reported its highest case numbers since 2017, with 233,251 reported dengue cases (12). Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan have also reported increased case numbers, due to unprecedented heavy rains and flooding that coincided with monsoon seasons (13, 14, 15). Current global reports on dengue cases indicate a rising trend, due to factors including climate change, rising temperatures and flooding (16).

Table 4. Cases of dengue by region of travel, 2022

| Region of travel | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Southern Asia | 248 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 52 |

| Caribbean | 24 |

| Eastern Africa | 23 |

| South America | 20 |

| Central America | 15 |

| Western Asia | 8 |

| Western Africa | 3 |

| Middle Africa | 2 |

| Western Europe | 1 |

| Northern America | 1 |

| Not stated | 60 |

| Total* | 457 |

*Some cases travelled to more than one region; all regions are included here so the total may be higher than the actual number of cases.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by protozoan parasites from more than 20 Leishmania species. These parasites are transmitted to humans by the bite of 30 different types of sandflies (17). The disease has 3 main forms: cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), visceral leishmaniasis (VL), and mucosal leishmaniasis (ML) (18), and can cause skin ulcers, organ enlargement, and mucous membrane destruction. Leishmaniasis affects millions of people globally, with VL likely to be fatal if untreated. The disease is prevalent in parts of Africa and Asia, the Americas, the Mediterranean basin, and the Middle East (19).

In 2022 there were 51 leishmaniasis cases reported, all from England. This represents a 113% increase compared to 2021 (n=24), and an increase from the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 18 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019. While the exact reason for the peak in 2022 remains unknown, it is worth noting that these cases were reported in SGSS, which has data limitations. Case numbers were highest in the first quarter of 2022 (n=16) compared to later quarters in the year (n=13, n=10, n=12) (Figure 8). Of all cases in 2022, parasite species was only known for 18% of cases (n=9), and all of them were identified as Leishmania donovani complex, which unlike other species can cause visceral leishmaniasis.

Figure 8. Cases of leishmaniasis by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

In 2022, 13 cases (25%) were female (aged 2 to 82 years, median=26) and 38 (75%) were male (aged 1 to 76, median=26) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Cases of leishmaniasis by age group and sex, 2022 (n=51)

In 2022, travel history was only known for 1 case, who travelled to Belize in Central America.

Rickettsial infections

Rickettsial infections are a group of bacterial infections of the genera Orientia and Rickettsia, which are transmitted by different arthropod vectors, including ticks, mites, lice and fleas, to animals such as humans, dogs, cats and cattle. In general, the incubation period is between 6 to 14 days post infection and symptoms vary but may include fever, myalgia, headache, dry cough and rash (20, 21, 22).

Human rickettsial infections are classified into 3 main groups: spotted fever group, typhus group and scrub typhus group. Spotted fever group infections are caused by over 30 Rickettsia species such as Rickettsia africae, Rickettsia conorii sp., and Rickettsia rickettsii. They are transmitted by ticks and have a wide geographical distribution. Typhus group infections are caused by Rickettsia typhi and R. prowazekii and are transmitted to humans through louse and flea faeces mostly in Asia, Africa and the Western Pacific. Scrub typhus infections are mainly caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi and transmitted through the bite of infected mite larvae. They are endemic across Asia, the Western Pacific, South America and Africa and causes an estimated 1 million cases per year (21, 22).

In 2022 there were 31 cases of rickettsial infections reported in EWNI (30 in England and 1 in Wales), Of these, 17 (55%) were confirmed cases and 14 (45%) were probable cases. This represents a large increase compared to 4 cases reported in 2021, and slightly lower than the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 41 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019. Case numbers in 2022 were the highest in quarters 2 and 3 (n=10 and n=9) (Figure 10). Of reported cases there were 20 cases (65%) in the spotted fever group, 6 cases (19%) in the scrub typhus group and 5 cases (16%) in the typhus group.

Figure 10. Cases of rickettsial infections by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

In 2022, 10 cases (32%) were female (aged 17 to 68 years, median=45) and 21 (68%) were male (aged 21 to 76 years, median=48) (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Cases of rickettsial infections by age group and sex, 2022 (n=31)

In 2022, travel history was known for 29 out of 31 cases. Of these, the majority of spotted fever cases reported travel to Southern Africa (13, 57%) and Eastern Africa (4, 17%). All scrub typhus cases reported travelling to Southern Asia (6) and half of typhus group cases reported travel to Middle Africa (3, 50%) (Table 5). For all cases of rickettsial infection, the most frequently reported country of travel was South Africa (13), followed by India (3) and Cameroon, Mozambique, Eswatini and Sri Lanka, with 2 cases reporting travel to each.

Table 5. Cases of rickettsial infection by region of travel and rickettsial group, 2022

| Region of travel | Scrub typhus | Spotted fever | Typhus group | 2022 total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Africa | – | 13 | – | 13 |

| Southern Asia | 6 | – | – | 6 |

| Eastern Africa | – | 4 | – | 4 |

| Middle Africa | – | – | 2 | 2 |

| Western Asia | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Caribbean | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Central America | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Northern America | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Southern Europe | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Not stated | – | 2 | – | 2 |

| Total | 6 | 23 | 6 | 36 |

Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis can be an acute or chronic parasitic infection caused by trematode worms of the genus Schistosoma. Infection occurs when larval forms of the parasite, which are released into water by freshwater snails, penetrate skin when in contact with the contaminated water. There are 2 main forms of schistosomiasis, intestinal and urogenital, caused by multiple Schistosoma species, of which the most common are S. mansoni, S. japonicum and S. haematobium.

Symptoms are predominantly caused by the body’s reaction to eggs which are released by adult worms in the body. Clinical symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhoea, blood in the stool, haematuria (blood in the urine), anaemia and stunting. There may also be organ damage of the liver with portal hypertension in advanced cases, the urinary bladder, and other long-term consequences such as infertility. Schistosomiasis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, mainly in agricultural and fishing communities. It is estimated that 90% of people requiring treatment for schistosomiasis are resident in Africa (23).

In EWNI there were 123 schistosomiasis cases reported in 2022, all of these from England. This represents an 86% increase compared to 2021 (n=66), and an increase from the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 47 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019. Case numbers were highest in the first quarter of 2022 (n=42) compared to later quarters in the year (n=26, n=22, n=33) (Figure 12). Of all cases in 2022, parasite species was known for 17% of cases (n=21) with 14 cases infected with Schistosoma haematobium and 7 cases infected with Schistosoma mansoni.

Figure 12. Cases of schistosomiasis by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

In 2022, 77 cases (63%) were female (aged 15 to 82 years, median=29) and 46 (63%) were male (aged 17 to 73, median=41, Figure 13).

Figure 13. Cases of schistosomiasis by age group and sex, 2022 (n=123)

In 2022, travel history was only known for 7 out of 123 cases. The majority of these cases reported travel to Africa, with 3 cases (38%) reporting travel to Northern Africa and 2 cases (25%) reporting travel to Eastern Africa (Table 6). The most frequently reported countries of travel for these cases were Ethiopia (2) and Sudan (2).

Table 6. Cases of schistosomiasis by region of travel, 2022

| Region of travel | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Northern Africa | 3 |

| Eastern Africa | 2 |

| South America | 1 |

| Southern Asia | 1 |

| South-Eastern Asia | 1 |

| Not stated | 116 |

| Total* | 124 |

*Some cases travelled to more than one region; all regions are included here so the total may be higher than the actual number of cases.

Soil-transmitted helminth infections

Soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) are among the most common infections worldwide. They are transmitted via consumption of contaminated food or by walking barefoot in infected areas with worm eggs or larvae in soil (24, 25). The main species that infect humans are roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) and hookworm (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale), and together these account for the major burden of disease globally. These STH infections are all diagnosed by microscopy (there is no serological test for them), whereas Strongyloides stercoralis, the predominant Strongyloides species, requires charcoal culture of stool plus serology. Furthermore, microscopy is insensitive for this parasite, so for this reason it is frequently not identified. Unlike other STHs, S. stercoralis can reproduce within the human host and may be fatal in immunocompromised individuals. Symptoms from STH infections vary depending on the intensity of infection, and include intestinal manifestations, malnutrition, impaired growth and physical development. STH infections are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas, with the greatest burden occurring in sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas and Asia (24).

In EWNI, there were 262 cases of soil-transmitted helminth infection reported in 2022 (259 in England and 3 in Wales). Of these, 237 (90%) were identified as strongyloidiasis, 17 (7%) as ascariasis and 8 (3%) as trichuriasis. There were no cases of hookworm in 2022. This represents a 53% increase in STHs compared to 2021 (n=171) and is also significantly higher than the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 75 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019. Case numbers were highest in the first and last quarters of 2022, with 42 and 33 cases respectively (Figure 14). The exact reason for the increase in case numbers is unclear, however it is difficult to interpret trends in cases reported in SGSS due to data limitations. Additionally, the proportion of STH diagnosed as strongyloidiasis in EWNI differs from the global picture, where ascariasis generally has a higher burden globally compared to strongyloidiasis (26, 27). There is significant uncertainty surrounding the global burden of strongyloidiasis, which may reflect global patterns of testing and diagnosis.

Figure 14. Cases of soil-transmitted helminth infections by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

Figure 15. Cases of soil-transmitted helminth infections by age group and sex, 2022 (n=257)

Table 7. Cases of soil-transmitted helminth infections by region of travel, 2022

| Region of travel | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Eastern Africa | 1 |

| Northern Africa | 1 |

| Southern Africa | 1 |

| Not stated | 259 |

| Total* | 262 |

*Some cases travelled to more than one region; all regions are included here so the total may be higher than the actual number of cases.

Zika

Zika is a mosquito-borne infection transmitted by the bite of an infected female Aedes mosquito. It is caused by a virus from the Flaviviridae family. Less commonly, transmission can occur through sexual contact, congenitally from a pregnant woman to her foetus and though blood transfusion (28). The majority of people with Zika infection do not develop symptoms. Those that do often have mild symptoms which can include fever, headache, malaise, joint and muscle pain, a rash, itching, conjunctivitis and swollen joints (29). Serious complications are uncommon, however an infection with Zika is a cause of congenital Zika Syndrome (characterised by microcephaly and other congenital anomalies) and neurological complications such as Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

During 2015 to 2016, there was a large outbreak of Zika virus infection in the Americas and the Caribbean, leading to the first imported Zika cases in the UK. As of 2022, 89 countries across Africa, Europe, the Americas, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific have reported autochthonous Zika cases (30).

In 2022, there were 8 Zika cases reported, all of these from England. Of cases reported in 2022, 7 (88%) were confirmed cases and 1 (13%) was classified as a probable case. Case numbers were consistent across all 4 quarters of 2022 (Figure 16). This represents a large increase compared to 2021, when only 1 case was reported. However, this remains lower than the pre-COVID-19 pandemic average of 25 cases reported per year between 2015 and 2019.

Figure 16. Cases of Zika by quarter, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

Figure 17. Cases of Zika by age group and sex, 2022 (n=8)

Table 8. Cases of Zika by region of travel, 2022

| Region of travel | 2022 |

|---|---|

| South-Eastern Asia | 6 |

| Southern Asia | 1 |

| Not stated | 1 |

| Total* | 8 |

*Some cases travelled to more than one region; all regions are included here so the total may be higher than the actual number of cases.

Other travel-associated infections

Filariasis

Filariasis is caused by various species of filarial worms (nematodes) transmitted by mosquitoes and flies. Filariasis encompasses several different diseases, including lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, loiasis, and mansonellosis, each of these with different geographical distributions. Lymphatic filariasis is widespread across Asia, Africa, the Western Pacific, the Caribbean and South America (31).

Onchocerciasis predominantly affects 31 African countries, with 2 countries in South America and Yemen also affected (32). Loa loa parasites are found in Western and Central Africa, primarily in specific rain forests (33) and mansonellosis occurs in Africa, Central America, South America, and parts of the Caribbean (34).

In 2022 there were 17 filariasis cases reported, all of these in England. Three cases (18%) were identified as Loa loa, and the remaining 14 (82%) were unspecified filarial species. Sixty-five percent of cases were male, and the median age of cases was 56 years old. Travel history was not known for any of the cases. To note, filarial serology is very cross-reactive, including with non-filarial nematodes. However, the diagnosis method for cases is unknown due to data limitations with SGSS; the above data should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Japanese encephalitis

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a vaccine preventable mosquito-borne infection transmitted by the bite of Culex species mosquitoes. It is a flavivirus from the Flaviviridae family and is transmitted via mosquitoes to humans from pigs and water birds. Japanese encephalitis is found in 24 countries in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific, mainly in settings where humans live in close proximity to pigs and water birds. A vaccine is available; however this is only advised for travellers at increased risk of infection. Most people with JE do not develop symptoms but for those who do symptoms may include fever and headache or vomiting in children. Less than 1% of people develop severe disease, which is characterised by encephalitic symptoms such as disorientation, seizures, coma and paralysis and approximately 30% of these cases are fatal. For cases who survive, approximately 30% suffer long term cognitive, behavioural or neurological complications (35, 36).

There were no cases of Japanese encephalitis reported in EWNI in 2022. The most recently reported case in EWNI was in 2017 in a traveller who had visited Thailand.

Trypanosomiasis

Human trypanosomiasis is caused by Trypanosoma parasites. There are 2 main types: Human African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness), which is caused by T. brucei species and is transmitted by tsetse flies; and American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease), which is caused by T. cruzi and transmitted primarily by triatomine insects commonly known as ‘kissing bugs’. Both can lead to severe complications or be fatal (37). Human African trypanosomiasis is endemic in 36 sub-Saharan African countries, with the 2 subtypes found in different regions of Africa. American trypanosomiasis, once limited to the Americas (not including the Caribbean) is now increasingly detected in migrants to several European, African, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific countries, but is not endemic in these regions (38).

One case infected with the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite, which causes Chagas disease, was reported in 2022. The case was a female in the 20 to 29 age group. Travel information was unknown for this case.

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is a vaccine preventable mosquito-borne infection transmitted by the bite of multiple species of infected mosquitoes, including Aedes and Haemogogus species. Yellow fever virus is a flavivirus from the Flaviviridae family. Yellow fever is endemic in all or parts of 47 countries in Africa and Central and South America. The virus incubates in the body for 3 to 6 days post infection. Many people do not develop symptoms but for those who do, these may include fever, headache, nausea or vomiting, muscle pain (often with backache), and loss of appetite. Most people will make a full recovery after 3 to 4 days, however a small number (approximately 15%) will progress to a second phase of the infection and go on to develop jaundice, abdominal pain, renal failure and haemorrhage (bleeding). Up to half of infections in cases who develop severe symptoms may result in death. Yellow fever is rare in international travellers as there is a safe and effective vaccine available. Although the vaccine is safe, there have been reports of rate adverse events associated with its use (39).

Data for cases of Yellow fever was obtained from RIPL, UKHSA Porton.

In EWNI there were no cases of yellow fever reported in 2022. The most recently reported case in EWNI was in 2018 in a traveller who had visited Brazil.

References

1. UKHSA. ‘Notifiable diseases and causative organisms: how to report’ (updated 31 May 2023)

2. ONS. ‘Travel trends: 2022’

3. UNSD. ‘Methodology’

4. ONS. ‘Travel trends estimates: overseas residents in the UK and UK residents abroad’

5. WHO. ‘Chikungunya’ (updated 8 December 2022)

6. NCVBDC. ‘Chikungunya Situation in India’

7. WHO (2017). ‘Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper’

8. WHO (2021). ‘Cholera Annual Report 2021’. Weekly Epidemiological Record: volume 97 (37), pages 453 to 464

9. WHO. ‘Pakistan Floods Situation Report’

10. WHO. ‘Cholera – Global situation’ (updated 11 February 2023)

11. WHO. ‘Dengue and severe dengue’ (updated 17 March 2023)

12. NCVBDC. ‘Dengue Situation in India’

13. WHO. ‘Dengue – Nepal’ (updated 10 October 2023)

14. WHO. ‘Dengue – Pakistan’ (updated 13 October 2023)

15. WHO. ‘Dengue – Bangladesh’ (updated 28 November 2023)

16. Mondal N (2023). ‘The resurgence of dengue epidemic and climate change in India’. The Lancet: volume 401, issue 10378

17. ECDC. ‘Facts about leishmaniasis’

18. WHO. ‘Leishmaniasis’ (updated 12 January 2023)

19. NaTHNaC. ‘Leishmaniasis’

20. Premaratna R (2022). ‘Rickettsial illnesses, a leading cause of acute febrile illness’. Clinical Medicine Journal: volume 22, issue 1

21. Blanton LS (2019). ‘The Rickettsioses: A Practical Update’. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America: volume 33, issue 1

22. Warrell CE, Osborne J, Nabarro L, Gibney B, Carter DP, Warner J, Houlihan CF, Brooks TJG, Rampling T (2023) ‘Imported rickettsial infections to the United Kingdom, 2015–2020’. Journal of Infection: volume 86, issue 5

23. WHO. ‘Schistosomiasis’ (updated 1 February 2023)

24. WHO. ‘Soil-transmitted helminth infections’ (updated 18 January 2023)

25. NaTHNaC. ‘Parasitic worms (soil-transmitted helminths)’

26. Holland C, Sepidarkish M, Deslyper G, Abdollahi A, Valizadeh S, Mollalo A, and others (2022). ‘Global prevalence of Ascaris infection in humans (2010–2021): a systematic review and meta-analysis’. Infectious Diseases of Poverty: volume 11, issue 1

27. Buonfrate D, Bisanzio D, Giorli G, Odermatt P, Fürst T, Greenaway C, and others (2020). ‘The global prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis Infection’. Infectious Diseases of Poverty: volume 9, issue 6

28. WHO. ‘Zika virus factsheet’ (updated 8 December 2022)

29. PHE. ‘Zika virus: symptoms and complications guidance’ (updated 2 August 2017)

30. WHO. ‘Zika epidemiology update – February 2022)’

31. WHO. ‘Lymphatic filariasis’ (updated 1 June 2023)

32. WHO. ‘Onchocerciasis’ (updated 11 January 2023)

33. Whittaker C, Walker M, Pion SDS, Chesnais CB, Boussinesq M, Basáñez MG (2022). ‘Loa loa: More than meets the eye?’. Trends in Parasitology: volume 34, issue 4

34. CDC. ‘Mansonellosis’

35. WHO. ‘Japanese encephalitis’ (updated 9 May 2019)

36. Yun SI, Lee YM (2013). ‘Japanese encephalitis: the virus and vaccines’. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapuetics: volume 10, issue 2

37. WHO. ‘Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness)’ (updated 2 May 2023)

38. PAHO. ‘Chagas disease’

39. WHO. ‘Yellow fever’ (updated 31 May 2023)

[ad_2]

Source link