[ad_1]

To mark the 40th anniversary of the release of the first Swatch watch line-up, we revisit Richard Benson’s long-read on the rise of The Swatch Group from the Big Watch Book 2017.

“The thing about Switzerland,” says Carlo Giordanetti, the impeccably dressed and very Italian creative director of Swatch watches, “is that it values tradition. I mean, really values it. And Swiss watchmakers never set out to just fill up small containers with mechanisms. They set out to make things that have souls. They believe the mechanical movement of a watch has a soul, because it is a living thing with an emotional connection to you, because you’re the one who gives it energy by winding.”

Giordanetti — tailored mid-blue jacket and pocket square, tasteful spectacles, fervently demonstrative — is explaining the existential nature of the “quartz crisis” that led to the creation of the revolutionary Swatch brand in 1983. The basic business story — Far East manufacturers almost eradicate Swiss counterparts with cheap quartz wristwatches in the Seventies; maverick businessman Nicolas Hayek saves day by reinventing Swiss watch as fashion accessory — is well known. But, says Giordanetti, there was more to it than business.

The question was never, “Can you make a Swiss quartz watch to compete with Citizen and Seiko?” but rather, “Is it possible to make a cheap, mass-manufactured product that inspires the personal attachment and ‘soul’ associated with handcrafted equivalents?”

As he points out, the answer formulated by the Swiss and expressed in the form of kooky-looking plastic would exert a profound influence not only on wristwatches, but on the way businesses think about brands, technology and customers. And this year it has been enjoying renewed interest from a new generation of watch-watchers.

In 2017, Swatch means more than the single original brand whose first modestly sized range of 12 watches was launched in spring 1983. In 1998, it gave its name to the conglomerate from which it originated, and today the Swatch Group owns 18 watch brands; super-high-end names like Breguet, Blancpain and Longines and more affordably priced lines such as Rado, Tissot, Mido, Calvin Klein and Flik Flak, with Omega said to generate the most revenue.

The group owns 17 movement and component producers, including ETA, Switzerland’s largest supplier of mechanical and quartz movements. Like all Swiss manufacturers, the Swatch Group has been losing ground recently; in 2016, sales were down 10.6 per cent to 7.5bn Swiss Francs (£5.9bn), with profits falling 44.5 per cent to CHF805m (£635m). In 2017, however, two developments have prompted excited talk among commentators of a Swatch-led revival for the whole sector.

Firstly, CEO Nick Hayek reported an upturn in sales and predicted an increase of up to nine per cent by the end of 2017. Second, he announced the group was working on its own smart watch operating system to compete with Apple’s watchOS and Android Wear when it is released in a Tissot in 2018. This is a bold and important move, given that non-Swiss smart watches have taken substantial sales from Swiss manufacturers’ mid- and lower price ranges.

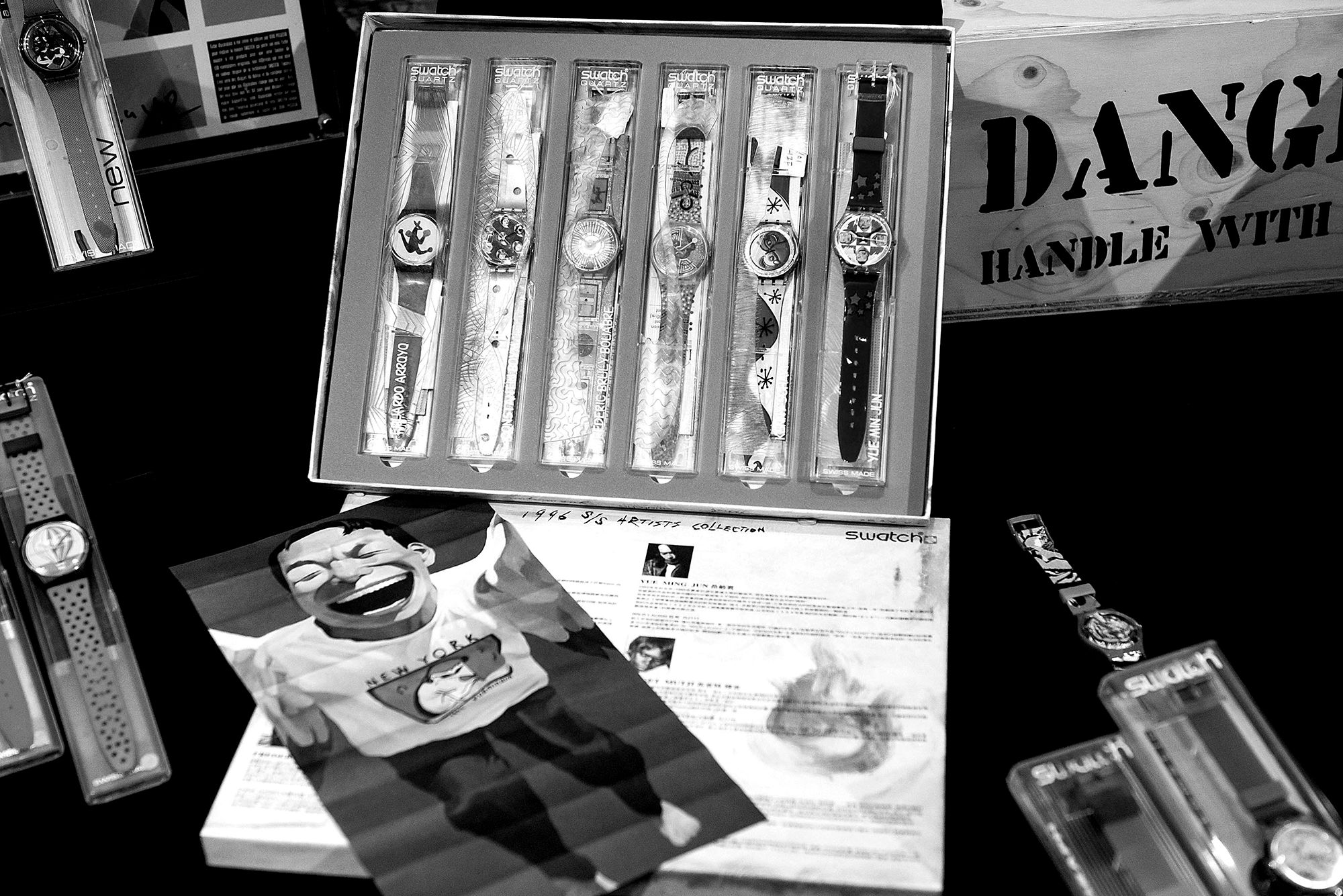

The buccaneering spirit inherent in the independent Swatch OS rather recalled the early years of the brand, with its new watchmaking paradigm and pioneering experiments with electronics (old-timers may remember the Beep pager watch of 1991, for example, or the groovy Musicall, with embedded Jean Michel Jarre track, in 1993). It kind of helped that the company had been in the news a couple of years earlier, when, in spring 2015, Sotheby’s sold the largest collection of Swatches ever auctioned, a 5,800-piece lot amassed by European collector Paul Dunkel, for $6m (£4.5m), five times the estimated price (the buyer was an unnamed “European institution”). In autumn that year, the auction house sold another collection, this time of more than 4,000 pieces owned by Swatch designers Marlyse Schmid and Bernard Muller, for almost $1.3m (£980,000).

When we meet at the Swatch Lab where Swatch’s creative and planning work is done — a somewhat secretive, low-rise converted bank in central Zurich, marked only with a discreet nameplate at the door — Giordanetti allows me into the basement to look at Swatch’s archives, which contain versions of many of the models sold in the auctions. It’s incredible, a sort of pop-art version of the Crown Jewels. To see these tiny, Fisher-Price-toy-coloured plastic treasures together is to marvel at how memorable so many of them are, but also to wonder at the magic that gave them so much value and, indeed, soul.

Dunkel called his sale, “A true testament to the universal appeal of Swatch,” and no one could argue. Down here among the art and the plastic, it’s easy to see why, as the company that once saved Swiss pre-eminence faces a new challenge, the world may once again look to Swatch for inspiration.

The story of Swatch begins with Switzerland’s quartz crisis, and the story of the quartz crisis begins in the Fifties. In World War II, Switzerland’s 2,000 or so watchmakers had prospered because their nation’s neutrality meant they could carry on watchmaking while their foreign competitors were contributing to war efforts. Consequently the Swiss dominated the post-war watch market, and enjoyed a near 50 per cent share of global sales.

The watches in question were mechanical, powered by hand-winding; or automatic, powered by the movement of the wearer’s wrist, with the energy converted by a rotor. Starting in the Fifties, there was interest among watchmakers in making timepieces that might use a battery as a source of power, as this would make the watch more accurate, and cheaper. When you wind a mechanical watch, you essentially stretch a spring which, on contracting, turns a tiny wheel (the balance wheel), converting the energy into a regular movement. Engineers realised that the spring-balance wheel could be replaced by a tiny quartz crystal, because when quartz vibrates at high speed, it produces electricity at a very precise, regular frequency. Make quartz vibrate with an electrical signal from a battery, and it will drive a cheap mechanism that does what

a spring wheel does, but more accurately.

Through the Fifties and Sixties, Swiss, American and Japanese watch and electronics companies competed to perfect a quartz wristwatch. There were several attempts and in 1967 the Swiss Centre Electronique Horloger, funded by major Swiss manufacturers, presented a fully developed Swiss quartz movement for a wristwatch. The major Swiss manufacturers then more or less ignored it while the Japanese and Americans seized their opportunity.

In December 1969, Japan’s Seiko released the Astron, the world’s first commercial quartz watch, and a couple of years later Hamilton of the US put on sale its Pulsar, the first electronic digital model. Other Far East and US companies such as Citizen and Texas Instruments began converting production lines. In Switzerland, Omega made a few, but really that was about it. When you ask people in the Swiss industry today why the old guard were so slow off the mark, they get a bit conflicted. Suggest it was because of a noble attachment to the old ways, and they’ll say no, they were just being typically insular. (“Switzerland is very self-contained, surrounded by mountains, and one of the issues in this market is that a lot of people tend to think this is the world,” says Giordanetti. “The quartz phenomenon was growing outside the borders of Switzerland, and until it really came into the market, it didn’t hit them.”) But say the old guys seemed to be stuck in the past, they’ll answer, well, yes, but you have to understand.

“Those [cheap imported quartz] watches were just stainless steel containers — sometimes not even stainless steel!” says Giordanetti, making a contemptuous flourish with his right hand, as if the idea is a personal affront to him. “They were just containers with a chip inside. There was no soul.”

Souls and mountains notwithstanding, once the Americans dropped out of the race in the late Seventies, cheap quartz watches from the Far East inflicted on the Swiss watchmakers the sort of decline that we in the UK associate with shipbuilding and coal mines. By the early Eighties, the Swiss had fallen from first to third in the international sales league, behind Japan and Hong Kong. Between 1977 and 1983, their share of the world market went from 43 per cent to 15 per cent, and the workforce declined from 90,000 to around 40,000. About 1,000 brands, including venerated companies such as Cortébert, Marvin and Enicar, disappeared, while others desperately amalgamated to try to survive.

In 1979 (some sources say 1980 but official Swatch history suggests it must have been earlier), the banks that were effectively keeping the Swiss watchmakers afloat brought in Nicolas G Hayek as chief advisor, the founder and CEO of Hayek Engineering, a management consulting firm based in Zurich.

Hayek, a charismatic Lebanese businessman then in his early fifties, had founded Hayek Engineering in 1963, and earned a reputation for reviving European corporations. This time he was essentially charged with writing a report about the disposal of the remains of the industry, and his response would go down in business lore as one of the great examples of successfully ignoring a brief.

Hayek believed that if the businesses were rationalised and the brands reinvigorated, the industry could be saved. The precise dates and details of what happened are extremely difficult to pin down because of conflicting accounts; some (including Swatch itself) say he was directing developments that led to the creation of Swatch from 1979, while others like the Harvard Business Review report that he didn’t take control until 1985.

What is clear is that his chief concerns were two companies, the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG, or ASUAG, and the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH). ASUAG owned, among other companies, Longines, Rado and Eterna, and SSIH had Omega, Tissot and Hamilton. Rather than file a report explaining how best to sell off their brands to the Japanese, Hayek oversaw their amalgamation into a new company (Société Suisse de Microélectronique et d’Horlogerie, or SMH), took a controlling stake himself and brought in a consortium of new investors.

Once in charge, he quickly moved SMH’s famous brands such as Omega and Longines upmarket, increasing their retail price and adding the words “Swiss” or “Swiss Made” to the pieces’ dials to emphasise the heritage. However, what he really needed was a mountain of ready cash, and a gentle move upmarket was not going to generate that.

“You have to understand, they were in deep shit,” says Giordanetti, who joined the company in 1987. “It needed to turn around fast. Yes, they could have made watches in stainless steel and sold more, but they needed to sell huge numbers, so many that they would create enough cash to transform the whole system of making and selling Swiss watches. So, how do you make and sell a volume product in large numbers? You lower the price. How do you lower the price? The easiest way was to reduce the number of components. But watch movements are complex, even in a quartz watch. So how could this be done?”

The answer lay with a small group of engineers at ETA who, since the late Seventies, had been locked in a nerdy, unofficial competition with counterparts at Seiko to create the world’s thinnest watch. It had become known as the “Delirium Tremens” project, after one them referred to the quest as “un delirium très mince” (“a very thin delirium”). The ETA team had won, getting below 2mm by placing some components on the case back — effectively doing away with the case as a separate, thickness-boosting element, making it a part of the movement. It was made of gold, the only acceptable material with the necessary strength and flexibility, and put in a Concord-branded “case”, priced at $10,000, and launched in 1979, whereupon it enjoyed decent but unspectacular sales in the US.

Noticing the Tremens project soon after it launched, Hayek gave the engineers a new brief. They were to design a watch that was cheap enough to compete with the Far East; had fewer components, but didn’t compromise Swiss quality; could be adapted to a range of products; was tough and waterproof, and was profitable. As Frank Edwards, author of Swatch: A Guide for Connoisseurs and Collectors, says, Hayek knew “that these criteria made it impossible to solve the problem by conventional watchmaking methods”. The point was to force them into coming up with “a completely new solution” that would change the paradigm of Swiss watchmaking.

The project was led by a manager and Hayek lieutenant called Ernst Thomke, with two young engineers, Elmar Mock and Jacques Müller, working under him in the ETA office. Mock and Müller hit on the solution after about 12 months, referring back to the Tremens. Their case would have every immobile part of the quartz movement attached to it, reducing the usual 100-odd components to 51. As they couldn’t use gold, they asked what other materials could provide the necessary flexibility, workability and strength to make such a case. The answer was wood and plastic, and they chose the latter, specifically an injection-moulded thermoplastic specially created with chemical engineers from one of Switzerland’s many chemical companies.

“The case is the real innovation Swatch was built on,” says Giordanetti. “It changed the whole paradigm of watchmaking, because with conventional watches, you begin by assembling the movement. With this, you began with the case. It was the opposite of what anyone had ever done before. That and the plastic meant it could have a low price and the low price helped drive the sales.”

Swiss feelings about said plastic may be revealed by the project’s initial name of Delirium Vulgare, but Hayek approved. According to Swatch’s official history, it was he who saw the potential for a “second watch”, a watch that would not be the heirloom piece of Swiss tradition, but “a new, fascinating way to say who you are and how you feel”. He ordered prototypes to be made, and the first arrived at ETA in mid-1981, now under the name “Delirium Popularis”.

Initially — and, it seems now, incredibly — the idea was to follow ETA’s usual model and supply unadorned watches to someone else who would brand and sell them. This strategy idea was abandoned after a trial distributing the watches in Texas in 1982 turned into, as Giordanetti says, “the biggest failure ever! They sold hardly any. After that, they realised that Texas and Middle America was not the target market, and this needed to be a product for customers who understood lifestyle and the evolution of taste.”

Which is how the Swatch brand came to be invented. According to The Innovation Factory, a book co-authored by Elmar Mock and academic Gilles Garel, the man with the greatest influence on the branding was a Swiss marketing consultant called Franz Sprecher, who had been brought in by Thomke. According to Mock, it was Sprecher who came up with the name, after spotting people in the company’s US ad agency SSC&B Lintas abbreviating “Swiss Watch” to “Swatch” (some sources claim it was intended as a portmanteau of “Second” and “Watch”). It was Sprecher, too, who devised the strategy of marketing the watch as if it were a fashion item, with two new collections of watches a year, to be supplemented by occasional “specials”.

The idea of collections to be augmented by one-off limited editions was a marketing paradigm-changer to match the engineering innovation of the case. Up until the early Eighties, the practice of limiting an edition of a consumer durable had existed only in the world of premium, luxury goods. Swatch would take the idea and, as Giordanetti says, “make it democratic and fun, taking the language of luxury and applying it to plastic. It was a part of how we created ‘fashion watches’ as a new category in the market. Until then, no one had found the courage to say that watches could be about fast consumption, trends and fashion.”

The design was by a network of freelancers coordinated by a Swiss designer, Jean Robert, and the first collection of 12 models launched in Switzerland, Germany and the UK in March 1983. But it was not quite the confident finished article. The colours were conservative, having been chosen, in a last-minute attack of nerves, to match Swiss military uniforms in the hope the government would buy them for the armed forces if the project bombed. Most of the models had serial numbers rather than the later, famous poppy names, and prices ranged from CHF39 to CHF49.90; only later in the year did someone realise that selling them all at a universal CHF50 (£50 in the UK) would enhance their appeal.

“The price was very important,” says Giordanetti, being “psychological, not rational. They have always offered more value per Franc than many luxury watches whose brands don’t actually make the movements.” Crucially, with a production cost of only CHF10, there was a margin that could, potentially, generate the Matterhorn of cash Hayek needed to sort out the whole group.

The most significant of the early Swatches was not in the first collection, but was the first Special, launched in summer 1983. The Jelly Fish had a transparent strap and case, so that you could see the internal workings. It was the first such use of clear plastic, and felt very contemporary at a time when references to industrial machinery had become fashionable (Ben Kelly’s Haçienda, Neville Brody’s cogs and wheels in The Face, bands such as Einstürzende Neubauten and Test Dept). It was a huge hit, sold out within weeks, and these days original Jelly Fish in good condition have been reported to achieve upwards of $6,000.

According to Giordanetti, the Jelly Fish “was revolutionary because at the time the world was moving towards a dictatorial approach to design and good taste. With this, there was no design or decoration, because it was clear. Swatch had agreed that it would not reproduce designs, but the demand was so high they did it in the next collection, with slight changes. After that, the design team fought hard not to keep producing it, knowing that way it would become a cult. Hayek thought they were crazy, but in the end he listened, and that’s what led to the phenomenon of Swatch collecting.”

Contrary to myth, he says, Hayek wasn’t really a savvy marketer when he set out. He became one by knowing when to listen. Thanks in no small part to the Jelly Fish, and a more adventurous second collection in the autumn, Swatch hit the 12-month sales target of one million three months early, in December 1983. “Zeitgeist is an abused word, but not in this case,” the British design critic Stephen Bayley once wrote of Swatch’s impact. “Swiss quality entered the mass market, not as a bit of craft-produced, hand-me-down eternity, but as a fashion accessory you might change weekly. It had a great name, strong advertising and… suddenly, buying a watch was amusing.”

In design terms, Swatch really hit its stride in 1984, when the colours and faces and packaging became more adventurous (this was the year of the iconic, none-more-Eighties Don’t Be Too Late and Grey Memphis models, now worth around $600 (£460) and $1,200 (£920) respectively) and sales worldwide hit 2.4m. If there was a challenge now, it was to establish a seriousness that would prevent the brand being seen as a fashion fad and in 1985 it pretty much achieved that with launch of the Swatch & Art category.

Swatch & Art watches, created in collaboration with artists and designers, have since been designed by hundreds of creatives including Keith Haring, Vivienne Westwood, Robert Altman, Akira Kurosawa, Pedro Almodóvar and Joana Vasconcelos. The first, in 1985, was France’s Kiki Picasso (real name Christian Chapiron), whose Kiki design was produced in an edition of 140, all slightly different. Today, the Kiki is the single most valuable Swatch, worth around $20,000 (£15,300), although according to Frank Edwards, a pristine 1986 set of four Keith Harings in the acrylic display will fetch between $60,000 and $80,000 (£46,000–£60,000).

Swatch would launch many more categories, or “families”, but if any single one captures the brand’s achievement, it is probably the Art line. Giordanetti thinks artists were attracted by the mission (Swatch had said one of its aims was to bring art into everyday life) and “the duality of being extremely democratic but also extremely desirable. If we hadn’t kept that duality, the Art would not have worked.” Art & Swatch had shifted the whole idea of value; it wasn’t about materials and craftsmanship and age, but about ideas and Getting It. It had brought watches into pop culture and pop into watches. Andy Warhol collected them. In 1986, Sotheby’s held the first Swatch auction in Geneva. By 1992, SMH had sold 100m Swatches, making profits of more than CHF400m.

There have been many, many significant developments in design and technology after that, of course. Bringing in more Italian designers, and then moving the design to a Milanese studio in the late Eighties boosted Swatch’s fashion-consciousness. (Giordanetti points out that Switzerland’s proximity to Italy, and Italians’ love for Swatches, means there has been a strong “Italian” feel to the brand.)

In the Nineties, the brand opened a New York design studio that brought in a reinvigorating edginess and awareness of online culture. There have been phones, sunglasses, the Mercedes car project, giant Swatches, steel Swatches and, in 2014, the Sistem 51 — a previously unthinkable Swatch mechanical watch with entirely automated assembly. Jay Deshpande, former editor of WatchTime, wrote on the Slate website that the invention of an affordable Swiss mechanical was potentially as revolutionary as the Apple Watch.

Not everything has been successful, concedes Giordanetti, but one advantage of releasing multiple collections and editions every year means you get to cover your tracks quickly. (Could he be thinking, one wonders, of 1998’s hubristic attempt to reinvent time itself with the Swatch Beat, which divided the day into 1,000 “beats”, and used Swatch HQ in Biel as its meridian?) Anyway, different things sell in different markets. In France, they like “a certain kind of green, a certain kind of purple, a certain kind of blue”. In the US, “you have to do white and pastel watches,” but Swatches still don’t really sell in Middle America. Russians like a “lot of our more crazy stuff”.

China, meanwhile, changed “almost literally overnight, in 2013. It had previously been a very bling-bling market. You could put a diamond on top of anything and it would sell three times more. It was great! But in 2013, China’s government passed laws banning officials receiving — and using public money to buy — luxury goods as gifts. Around the same time, wealthy Chinese people were beginning to travel more, and they started to learn that you can express luxury through other things.”

The big difference now, he adds, is that as people do travel more, they buy more things outside their own country, so retailers in each country need to offer ranges with wider international appeal. It’s one reason why a modern UK shopper might see more watches and gadgets with, say, an American or Middle-Eastern look than in the past.

Nicolas Hayek stepped down as chief executive in 2002, and was succeeded by his son Nicolas Jr, who remains as company head. Hayek Sr died in June 2010 at the age of 82. Today, the Swatch Group’s brands sit across the full range of prices and demographics from fun to financier, though in reality, says Giordanetti, the research and expertise is spread through to the different territories of the empire. “The power and strength of the group lies in having a vision developing and regrouping research, know-how and expertise that all the brands can benefit from. Every brand is responsible for coming up with concepts and ideas to be developed, challenging the technical R&D departments, and for seeing the potential in the ideas being developed within other companies in the group.”

As for Swatch, the brand that gave the group its name, what is the lasting legacy, beyond the economic foundation? Nicolas Hayek used to say he thought it was showing that one could set up and run a successful global manufacturing business in Europe at a time when the prevailing wisdom said cheaper costs in the Far East had made that impossible. Giordanetti thinks it is to have changed the paradigm of watchmaking, “taking an object associated with the world of luxury and achievement and bringing to it the opposite qualities. Having the courage to say watches could be about fast consumption, trends and fashion.”

It’s surely necessary to add that Swatch also brought us the idea that an everyday consumer item could be a beautiful, even artistic, object and a means of self-expression; Apple iPhones, Nike trainers and Starbucks coffee among others all owe it some measure of debt.

It certainly had soul in the end, says Giordanetti. “This is the beauty of this project, that we were able to bring soul to the product at that low price through the stories it tells and through design.”

I ask him if he really believes in the soul stuff, and he looks rather like the Archbishop of Canterbury might were he asked to confess to a secret atheism. He talks again about the early days in the mid-Eighties, when he was living in Italy and Swatch launched there.

“We were the last market Swatch launched in, but Italy very quickly became the biggest market worldwide, because Swatch was an ideal product for Italians: you change it very often, it doesn’t cost much, and it hits our passion for fashion and looks. It also had what we call a little bit of snob appeal, meaning it was super-cool to be a rich guy who owned a boat and a Ferrari and wore a Swatch because it showed he had nothing to demonstrate any more. Because, you see, you don’t always need a gold watch to show that you’ve made it.”

[ad_2]

Source link