[ad_1]

This year, like every year, Hong Kong’s banking circles have been peppered with farewells for senior executives. The glittering bars of Lockhart Road and Lan Kwai Fong have seen many bottles of champagne uncorked, tearful speeches delivered and group selfies taken in a natural cycle of change that starts toward the end of each calendar year as senior rainmakers depart for London, New York, Tokyo or Frankfurt. This year, however, few replacements are flying in.

Most of the banks whose headquarters dot the waterfront of Victoria Harbour have seen a steady erosion of those in the top positions as their functions are transferred elsewhere. The banks insist they are not moving their operations, but headhunters say the hollowing out of important personnel on many desks is being camouflaged by an expansion in wealth management functions tailored to mainland Chinese.

Most blame Hong Kong’s uniquely stringent Covid-19 regulations — arguably the toughest pandemic border controls in the world. These are aimed at synchronising the city with mainland China’s strict zero-Covid policies and have meant brutal quarantine stays of up to three weeks for anyone flying in. But while the goal has been to open up travel with China, so far this has failed. The doors to the mainland have been shut for more than 18 months, and so too is the gate for international travellers into Hong Kong.

The restrictions remain despite the fact that many other regions competing with Hong Kong for the mantle of Asia’s financial centre are lifting travel bans and easing quarantine requirements. Japan this month opened its borders to business travellers for the first time since January, while Singapore has been opening up “vaccinated travel lanes” with several countries, including the US, UK, and Australia, since September, whereby travellers can enter the country and forgo quarantine provided they are fully vaccinated and produce a negative PCR test on arrival.

JPMorgan chief executive Jamie Dimon, who was granted quarantine exemption when he arrived in Hong Kong on November 15 for a 32-hour trip, told reporters that Hong Kong’s Covid-19 rules had made it more difficult to retain and attract talent. He was given his exemption in “the interest of the city’s economic development”, according to Carrie Lam, the city’s chief executive, answering questions the following day.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

Since the handover of sovereignty to China in 1997, Hong Kong’s central role as a business hub has been reinforced by its openness to the outside world and its access to the mainland. Now it has neither, and no public timetable for when these will be coming back.

For many in the business community, the restrictive measures are the last straw and yet another sign that the city — increasingly under the sway of Beijing — has become inhospitable for international business.

The measures follow two years of turmoil that saw citywide protests against the government during 2019. Chinese president Xi Jinping stepped in with a draconian national security law last year that has set the city on a more authoritarian path. Civil servants have had to pledge their loyalty to the city, and free speech has become more restricted as authorities punish protest phrases with imprisonment. A newspaper critical of the government was forced to shut down.

Hong Kong officials urge businesses to be patient; the ultimate appeal of Hong Kong is its access to the mainland. “On the one hand you have the mainland, our biggest trade and investment partner, a lot of cross-people connections [between Hong Kong and mainland China], but then we are also a global financial, shipping, and trade centre,” said Regina Ip, an adviser to the chief executive and lawmaker. “How do we mediate, navigate the two requirements?”

But business lobbies complain that there is still no timetable for free movement with the mainland — and meanwhile, the restrictions mean less business from the outside.

“We don’t know anything about talks happening between [Hong Kong and] mainland authorities, certain criteria need to be met, in order to harmonise the way Hong Kong deals with the pandemic, compared with the mainland,” said Frederik Gollob, chair of the European Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong. “It’s a real headache.”

At some point, business people say, a tipping point will be reached.

“In the past, Hong Kong was the only choice for top Asia-Pacific roles,” said the Asia-Pacific head of markets at a global bank. “Today, we run into several hurdles: from the global heads posing whether we could use the opportunity to pick Singapore perhaps, to risk managers assessing if the role is suitable in Hong Kong, to the prospective bankers themselves asking if they could go elsewhere.”

Priorities and promises

The once freewheeling economy began shutting out non-residents in March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, and has maintained a strict 14 to 21-day quarantine for those coming into the city from China or overseas irrespective of vaccination status, which has successfully stamped out Covid-19 without the need of a citywide lockdown.

Lam, the city’s top official, last month made it clear that China was the priority — it would open to the mainland first. “Of course, international travel is important, international business is important, but by comparison, the mainland is more important,” Lam said in October. Global companies “also have businesses on the mainland, so it is important for them to be able to cross the border to take care of and attend to their businesses. So the most important thing is to open the border.”

But such rules could isolate Hong Kong, sending investment and talent elsewhere. Headhunters say the likely extension of such measures is pushing expats, who make up a tenth of the city’s population of 7.5m and are among its biggest earners, to rethink their stay, while newcomers are reluctant to come.

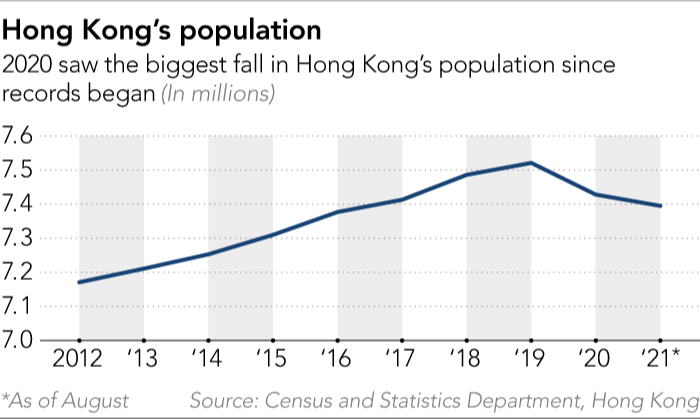

There is a risk of a brain drain; the transformation has provoked a population outflow, declining 1.2 per cent in 2020, the biggest fall since records began in 1960, and the trend is expected to continue this year. School enrolments have dropped, tens of thousands of local residents have fled to the UK, and pension fund withdrawals, which are made possible only when one leaves the city for good, have hit a record high.

In fact, the harsh quarantine policy is only the most visible of a host of efforts to synchronise Hong Kong with the mainland, often to the detriment of the city’s traditional openness to the outside world.

For example, the city’s lawmakers recently pushed through a record number of legislative acts that could create obstacles for foreign commerce. Hong Kong SIM cards will be linked to people’s identity, phasing out the use of prepaid SIMs in what authorities say will assist in fighting crime. Critics say the move, which mirrors mainland China’s policy, will increase government surveillance.

The US in July issued a business advisory warning American companies of the heightened risks. International concerns have also led tech corporations to axe undersea cable projects that would have enhanced telecommunications and made Hong Kong a global data hub.

These changes have also forced media organisations to rethink their stay after authorities began refusing visas for journalists, a common tactic used by Beijing. The New York Times moved its regional bureau to South Korea, while local news outlet Initium Media relocated its main operations to Singapore.

Quarantine in the extreme

Now, the addition of coronavirus restrictions has many questioning the status of “Asia’s world city”. Even the heads of the biggest businesses in the city have had to put up with the restrictions, causing irritation.

Mark Tucker, the chair of HSBC Holdings, the largest lender in Hong Kong, had to spend three weeks in isolation before he could meet staff and clients. Some of HSBC’s other executives, including its divisional head and co-heads of Asia, have all been subject to quarantine as they relocated to the city.

But the frustration often begins even before arriving in Hong Kong. A limited number of government-approved hotels are often sold out within hours of being made available. With demand on the rise ahead of Christmas, the government is to increase the number of rooms to 11,500 beginning December 1, according to an October government statement.

A head of sales at a global financial services manager recently moved to Hong Kong after four years in Sydney, spending more than 35,000 Hong Kong dollars ($4,492) on a 14-day quarantine in a 25 sq m room. He told Nikkei Asia the stress quarantine would put on his children prompted his decision to relocate without his family.

“Two weeks in a room alone with a fair bit of office work is do-able,” said the executive. “But the misery and mental toll it will inflict on children is immeasurable.”

Ben Cowling, a University of Hong Kong epidemiologist who underwent a 21-day quarantine in October upon his return from the UK, questioned whether the final week of the sequestration was necessary, pointing to mainland China’s 14-day hotel and seven-day home quarantine combination implemented in most places but Beijing.

“That’s the area where I question whether it’s justified,” Cowling said. “Because the third week has very limited benefits. According to government data there’s only a very small number of people who are tested positive on the third week.” Cowling added that policies implemented should be “evidence-based”.

The government repeatedly boasts of its anti-epidemic measures, reminding residents that the metropolis has not undergone a lockdown like other cities and countries. Hong Kong has logged fewer than 10 local Covid-19 cases in the past seven months, mostly from arrivals, yet restrictions are tightening to more closely mirror mainland China’s Covid-19 measures, including a mandatory 14-day quarantine for recovered Covid-19 patients, with a view to appeasing Beijing and convincing them to open borders.

“The mainland will be very careful and very strict to deal with this,” said Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, who last month was told not to travel to Beijing for a Chinese government meeting after an airport worker caught coronavirus. He said an app that could track and trace confirmed cases, close contacts and potential infections would have to be implemented. “Without it, the mainland won’t accept it.”

The Chinese government has successfully beaten waves of Covid-19 through its hardline approach, closing its borders and tightly controlling who can enter. Areas are locked down almost immediately and residents tested if a case is confirmed. On October 31, roughly 30,000 people were locked inside Shanghai’s Disneyland after one visitor was reported to be infected after visiting the theme park. Despite stringent measures, an outbreak of the Delta variant across 21 Chinese provinces continues to worsen.

One country, two systems

Current and former government advisers Nikkei Asia spoke to agreed that the administration has had to carefully consider the interests of all parties, navigating “two worlds, two cultures, two systems”, as one official put it. Hong Kong’s one country, two systems model, under which the city retains its own administrative and economic systems, as well as foreign trade relations, has attracted global banks and foreign businesses to set up regional headquarters there.

Officials believe the dissatisfaction or business loss, should there be any, would be short-term, as the government has held a handful of discussions with mainland health authorities. The administration has been tight-lipped on the details, and has repeatedly stressed the exchanges have been “constructive and conducive”.

The officials said Xi had risked Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan international reputation with his determination to tame the city and bring it under control with the national security law. Lam’s decision to open up to the mainland had shown where the government’s loyalty lay, signalling that China would always come first, they said.

“We have to choose which one, and we have decided,” said Jeffrey Lam, vice-chair of the Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong and adviser to the chief executive, referring to the decision between foreign countries and the mainland. “I support Ms Lam, and I think Hong Kong is acting as a gateway in and out. You have to first get that open.”

While foreign corporations have welcomed the news to open borders with the mainland, they point out there is no timetable, and thus no pressure to make good on this promise. Opaque meetings between Hong Kong and mainland health experts and tight control of official information have only added doubt.

Gollob told Nikkei Asia that the restrictions had deterred expatriates from moving to the city. “It is really difficult to convince people at this point in time to relocate to Hong Kong,” he said.

In an open letter in August addressed to Hong Kong’s chief executive, Gollob urged the government to communicate a clear exit strategy, as a continuation of the current situation could pose “a growing threat to Hong Kong’s status as an international business centre.”

Jumping ship

Forty-seven foreign regional headquarters have exited the city this year, according to government data. The regional bases that left were mostly from the US, Japan and France, but the number of mainland China regional offices have increased by 14, offsetting the departures.

“We’re treating Hong Kong like mainland China in terms of risk assessment,” said one senior executive at an international bank that has moved its regional operations out of the city. “We’re looking at other places in the region, perhaps more east.”

More than six global banks and at least four asset managers have relocated their headquarters out of the city, including Germany’s Commerzbank, according to a tally by Nikkei Asia.

Commerzbank did not respond to a request for comment.

Citibank said its “local and global clients continue to be very active in Hong Kong and the priority remains on supporting them. We are thus seeing strong client-led growth in Hong Kong [revenues up double digits year on year] and have hired several hundred in 2021, including in wealth, to support our wealth hub here.”

Hong Kong still maintains its ability to connect mainland China with the world and an increasing push to integrate into the Greater Bay Area will boost its allure, according to the government. But, travel restrictions have caused an “inconvenience”, commerce and economic development secretary Edward Yau admitted.

“The feedback and figures despite this backdrop remains pretty strong. I’m not trying to paint a rosy picture, that’s a constant struggle,” Yau said, referring to Covid-19. “But I can see strong resilience and also a collective picture giving me a sense of comfort that I’m trying to share.”

Across the city, the number of mainland Chinese companies has climbed to 2,080, almost as many as Japanese and US companies combined. A number of Chinese companies have decided to move their listings to the city, and the number of government policies enhancing Hong Kong’s role in the Greater Bay Area has been growing. Yau also highlighted the stable environment that businesses could enjoy.

“I think the presence of mainland companies in Hong Kong is showing Hong Kong’s role beyond just a city within the mainland,” Yau said.

A bankers’ paradise no longer?

But feedback from foreign companies paints a different picture. The Asia Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association (ASIFMA), a lobbying group for financial companies, said 90 per cent of its members who responded to its survey said they had been “moderately” or “significantly” impacted by travel restrictions. Almost three-quarters of the mostly international institutions were experiencing difficulties in attracting and retaining talent, with half contemplating moving staff or functions away from Hong Kong.

“The rest of the world is moving on, and Hong Kong isn’t articulating a plan that gives individuals the certainty they need,” wrote Mark Austen, the chief executive officer of ASIFMA, in an open letter to the government. “Some firms are moving operations, it’s not a huge amount right now. The longer this goes on, the more difficult it is for companies to keep those positions in Hong Kong.”

The liveability ranking of HSBC’s 2021 Expat Explorer Survey showed that Hong Kong plummeted to 40th from 20th last year, and slumped to 41st from 15th in the future outlook ranking. Overall, the city now ranks lower than Thailand and just ahead of the Philippines. Singapore ranked ninth and Taiwan 15th in the global survey.

“It is undoubtedly one of the toughest questions that we are facing at this point,” Nicolas Aguzin, the chief executive of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing and previously the chief of JPMorgan’s Asia-Pacific business, said of the city’s quarantine restrictions. “Everyone that has connections with the outside world, in particular in the financial sector, of course, is very eager to re-engage and to go back to the connections that we’re used to having in person.”

The city’s economy, meanwhile, suffers. It expanded 5.4 per cent during the 12 months leading to this year’s third quarter, lower than the 5.7 per cent consensus expectation of economists, who said a recovery now hinged on reopening.

While the dealmakers themselves may move back to their home base in Europe or the US, the roles are being relocated largely to Singapore, which has opened up and is a financial centre in its own right, and Shanghai, where global banks are busy setting up their fully owned operations. This is despite banks and multinationals postulating that they are committed to the city, and the local administration claiming that Hong Kong remains open for foreign businesses.

Global banks, which for decades have homed in on Hong Kong as the headquarters for their Asia-Pacific ex-Japan operations, are struggling to fill the ranks or attract talent to the city.

A July survey of 190 finance professionals across the Asia-Pacific region by recruiter Selby Jennings showed 69 per cent of those surveyed in Hong Kong were eager to move to Singapore.

The regional rival and neighbour, which has similar tax-friendly policies and ease of setting up a business, has established quarantine-free travel corridors with numerous countries over the past few months, drawing expatriates with families, investors and businesses who often prefer face-to-face meetings.

“With the coronavirus, it triggered [the desire to relocate] and acted like a catalyst,” said Arnaldo Oliveira, founder of recruitment agency Orion Executive Search International.

“Apart from banks and hedge funds, we see industries like retail that are moving out of Hong Kong too,” he said.

But the movement is not all one-way, with the city aiming to become the financial linchpin for Chinese president Xi Jinping’s ambitious Greater Bay Area, which also encompasses Macau, Shenzhen, Guangzhou and seven other Guangdong Province cities in the mainland’s increasingly affluent southern region.

The Greater Bay Area is home to 86m people and boasts a $1.7tn economy, similar in size to Canada. A wealth management connect scheme linking Hong Kong with the region was established in September, adding to the successful stock and bond connect programmes that cement the city’s role as the gateway to the mainland.

The wealth connect scheme promises hundreds of millions of dollars in fees, prompting the likes of HSBC and Citigroup to expand their wealth management staff. HSBC said this year it would add 5,000 wealth planners in Asia, primarily in mainland China, Hong Kong and Singapore, while Citigroup has unveiled plans to add 1,000 employees to support expanded wealth management in Hong Kong.

In a survey of 2,100 businesses in 10 markets from the US to Australia by HSBC in September, three in four respondents said they expected to set a foothold in the Greater Bay Area over the next three years.

Still, the easing of border rules is pivotal for Hong Kong to bounce back and grab some of these opportunities. Despite reassurances from the government that the city will open up as soon as possible, that decision lies not in Hong Kong’s hands, but in Xi’s.

“There are some sacrifices, some people will have to forgo meeting their business partners, but overall the economic performance tells us that it’s a price worth paying,” Yau said. “We’re still moving in the right direction. Hopefully, we’ll get out of the woods soon.”

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on November 17. ©2021 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved.

Related stories

[ad_2]

Source link