[ad_1]

Some low-income households who were electronically robbed of the funds they use for food and denied reimbursement may soon get their stolen benefits reinstated.

In recent months, thieves using hidden “skimming” devices have targeted a growing number of participants of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP.

The majority of states have declined to reimburse SNAP skimming victims. The U.S. Agriculture Department has said it does not keep a state-by-state list of skimming claims, but in Massachusetts alone, more than $1.6 million in SNAP benefits was stolen from over 5,000 households from June to November, according to the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance.

If Congress’ massive $1.7 trillion funding package passes, a provision tucked inside it would require states to replace SNAP benefits stolen in October or later.

SNAP participants receive monthly benefits for groceries deposited onto electronic benefits transfer, or EBT, cards. Advocates applauded the federal provision, pointing out that other consumers have long enjoyed stronger protections than EBT cardholders if their credit or debit card information is stolen.

“It is never your responsibility to be at a loss for those funds. Your credit card company will reimburse you,” said Ashley Burnside, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP). “So it is inequitable and unfair that if you’re using a different card solely because you’re a recipient of SNAP benefits, that if you fall victim to the exact same thing, that is your fault.”

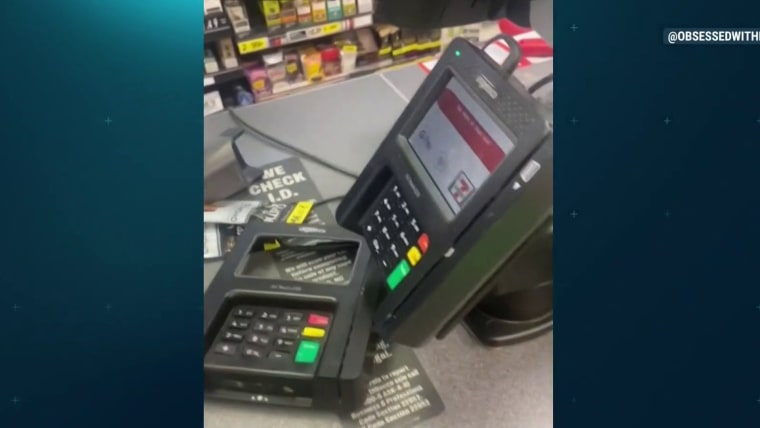

The theft typically happens when skimmers place devices on card-swiping machines at cash registers. The devices are often plastic keypad overlays that look nearly identical to the card reader terminals themselves. (See a picture of the skimming overlays here.)

When customers swipe their cards into machines, the skimming devices capture card data, along with PINs that have been entered, enabling skimmers to produce cloned cards.

It’s unclear who is behind the rise in SNAP skimming and precisely how they are spending the funds, which can only be used at designated retailers. The omnibus provision also calls on the Agriculture Department to issue guidance on SNAP skimming prevention and to collect data from states to determine the scope of the problem.

While skimming is not unique to EBT cards, security measures such as contactless payments and embedded microchips have combated it in the credit card industry. No SNAP state agency uses cards with chips, according to the Agriculture Department.

Betsy Gwin, a senior attorney at the nonprofit poverty law and policy center Massachusetts Law Reform Institute, said she was pleased by the federal government’s proposed reimbursement solution in the omnibus, which legislators are racing to pass in the coming days.

But the provision has limitations. It would only cover people whose benefits were stolen from Oct. 1, 2022, through Sept. 30, 2024. And it would only allow for a maximum of two months’ worth of SNAP benefits to be reinstated, even if a household was robbed of more.

Gwin’s organization filed a class-action lawsuit against the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance in early November on behalf of skimming victims seeking to have their stolen benefits restored. Because many of those represented by the lawsuit had benefits stolen before the time frame that the federal provision covers, she said the lawsuit will still proceed.

The provision also does not provide a long-term commitment to reimbursement, said Rep. C.A. Dutch Ruppersberger, D-Md., who introduced a bill last month to help SNAP skimming victims get their benefits reinstated. His bill, which has bicameral support and bipartisan backing in the House, is awaiting hearings.

“This is a temporary fix and my bill is a permanent fix once and for all,” he said. Still, he added, the fact that some victims would be receiving help as part of the omnibus bill was “a gift for many Americans who are struggling.”

“We’re calling it a Christmas miracle,” Ruppersberger said. “I’m surprised and delighted.”

Why reimbursement has been withheld up until now

SNAP, formerly known as food stamps, is a far-reaching public assistance program: More than 41 million people across the United States participated in August, according to Agriculture Department data. Households with children account for 65% of participants, department data collected pre-pandemic shows. While the program is federally funded, it is administered by states.

Even if there is evidence that EBT card data was used thousands of miles away, just a handful of states, including California, Wisconsin and Michigan, will use state dollars to reinstate skimmed SNAP benefits, according to the American Public Human Services Association, which represents state and local human service agencies. Washington, D.C., also reimburses SNAP skimming victims.

In the rest of the country, where states have not committed to using state funding, skimming victims have no recourse because federal dollars had not been an option either. Current regulations prohibit federal funds from being used to replace stolen SNAP funds, according to the Agriculture Department.

Ruppersberger’s bill aims to do away with those regulations permanently.

Gwin said her group receives reports of new skimming claims every few days and said she is hopeful that she’ll soon be able to tell victims that they can get their funds back.

“We hear from another family, another individual, who is shocked and angry and upset to discover that they have lost their SNAP benefits and they don’t know where to turn for help,” she said. “I’m really relieved and happy that we will be able to tell them that some relief is coming for them.”

[ad_2]

Source link