[ad_1]

Remember the rise of the right? First Brexit, then Trump, then a wave of rightwing populism broke over Europe. There were dozens of news articles on the “rising tide of anti-immigrant sentiment”.

Except it turns out that in the west, 2016 was a high water mark for such views. This is true of almost all western countries, but the most dramatic shifts have come in the US, Canada and, in particular, Britain, where the share of people saying there should be strict limits — if not an outright ban — on immigration has more than halved from 66 per cent on the eve of the EU referendum to 31 per cent last year.

These trends may be a direct reaction to the rise of rightwing populism, according to a new paper by political scientists James Dennison and Alexander Kustov. They theorise that the unexpected success of anti-immigration politics may have shocked previously complacent moderates into vocalising their support for diversity.

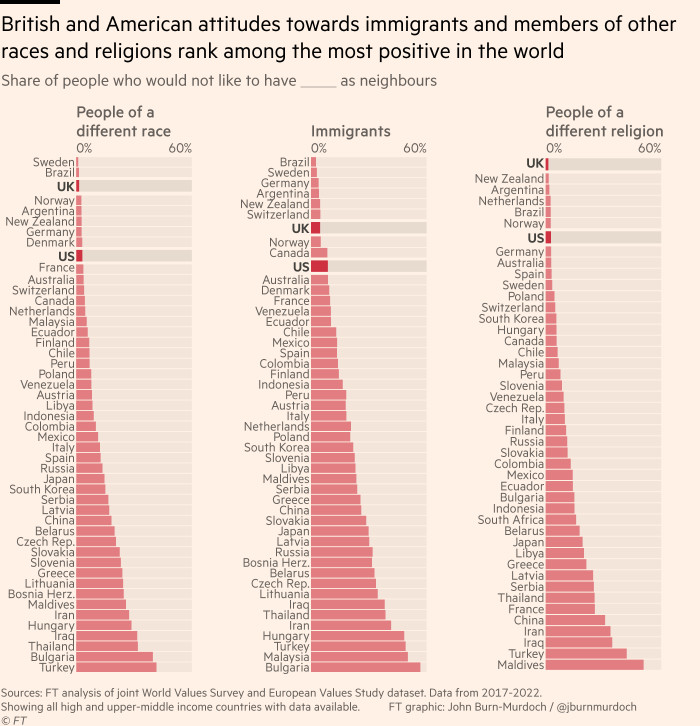

We see similar shifts in the general public’s attitude towards members of other ethnic groups and faiths. Just 3 per cent of Americans and 2 per cent of Britons say they would not want someone of a different race as a neighbour, with only Sweden scoring lower across the developed world. Discomfort with people from other faiths falls to just 3 and 1 per cent in the US and the UK respectively.

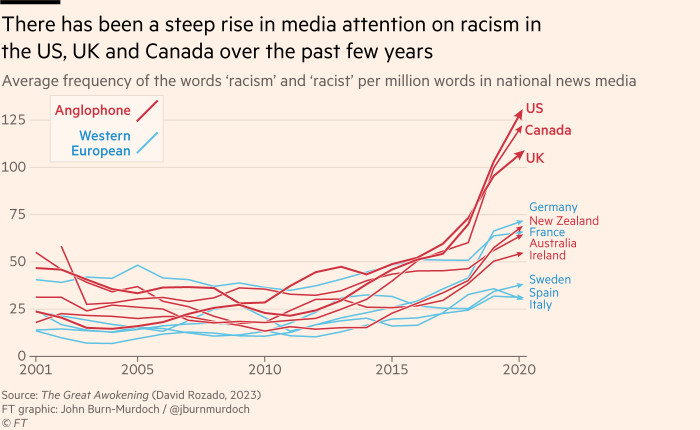

The data paints a picture of countries that are increasingly diverse — and increasingly relaxed about that fact. Yet it can often feel like things are going backwards. Mentions of terms that suggest ethnic prejudice have rocketed in western media over the past six to seven years, according to new research by David Rozado, an associate professor at the New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology.

In the west, concern about racial injustice is rising farthest and fastest in the UK, US and Canada — three countries where prejudice has reportedly fallen farthest and fastest. It’s a progressive paradox: the section of society whose values are clearly winning out remains deeply disquieted.

So why is this progress so rarely and reluctantly recognised?

One likely factor is the link between diversity and resulting solidarity with different racial groups. A 2020 study demonstrated that the more ethnic diversity someone encounters, the more they view people of different races positively. Racial stereotypes and hostility build when someone only encounters people from few, if any, other ethnic groups.

Considering Britain, the US and Canada are among the most diverse countries in the west and have been for some time, the attendant increase in racial solidarity might be why they have seen the steepest increases in concern about racial injustice.

But given that rightwing politicians use inflammatory racial language when diversity is increasing, aggregate levels of tolerance and isolated incidents of intolerance will often rise simultaneously.

Dennison and Kustov suggest that while populist phenomena such as Brexit and the election of Trump led moderates to reassert their support for diversity, they also emboldened the most prejudiced — as measured by spikes in hate crimes.

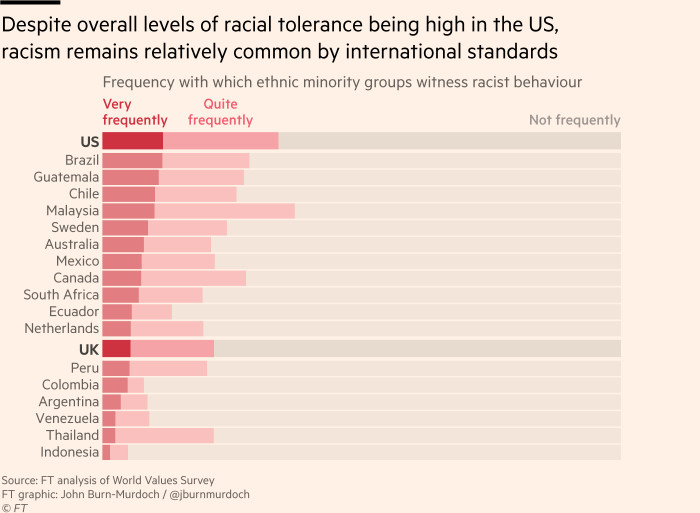

My analysis of the data from the World Values Survey suggests that this may be a particular issue in the US. Despite Americans as a whole ranking among the most comfortable with diversity, 12 per cent of US ethnic minorities say they “very frequently” encounter racist behaviour in their neighbourhood, the highest figure among 19 countries surveyed.

In the UK, that figure is 5 per cent — the lowest in Europe, but still 5 per cent too high.

Statistics like these sum up the progressive paradox. Britain, along with other western nations, has made huge strides and is now one of the most happily diverse societies in the world, but greater racial cohesion brings increased sensitivity to racial injustice. What is sometimes divisively referred to as the “great awokening” is, in fact, a rational response to a positive trend.

john.burn-murdoch@ft.com, @jburnmurdoch

[ad_2]

Source link