[ad_1]

In response to criticism for not disclosing its Scope 3 emissions as part of its net-zero pledge, Malaysia’s national oil company Petronas says that it will first need regulatory support to mandate emissions reporting across its value chain.

“What we do not want is for (our vendors and customers) to start capturing data on their Scope 1 and 2 emissions …just because that’s what Petronas wants them to do,” said the company’s chief financial officer Liza Mustapha. “It’s got to be something regulated, something that (they) feel is the right thing to do.”

Speaking at a dialogue with international media last month, Liza explained that Petronas did not want to foster a system in which third parties rely on the oil giant to incentivise or compensate them for reporting their carbon emissions. Scope 1 and 2 refer to direct emissions and indirect emissions from energy purchased, respectively, while Scope 3 covers all other indirect emissions, including those related to the use of its products.

In other words, Petronas’ Scope 3 emissions must account for the Scope 1 and 2 emissions of its customers and suppliers.

“It’s not that we’re ignoring Scope 3 because we do understand that it is important. The challenge is understanding how to measure someone (else’s) utilisation of your product and … not being able to control how they use your product,” said Liza.

Environmental activists in Malaysia have criticised Petronas’ failure to include Scope 3 emissions targets as part of its aspiration to achieve net-zero by 2050. In July, Malaysian environmental watchdog Rimbawatch also questioned the accuracy of Petronas’ reported emissions, pointing out that although the company said it was as yet unable to fully measure its emissions, they had in fact reported their Scope 3 in their 2022 integrated annual report based on the emissions of the companies they have stakes in (known as the equity share approach) and can control (known as the operational control approach).

“Can we trust Petronas’s emissions disclosures in general, noting that they have not received independent third-party verification, and that having this verification process is a standard practice by companies disclosing their emissions worldwide?” Rimbawatch asked in an open letter to the media. Petronas said that it is planning to get its Scope 1 and 2 emissions under the equity share approach assured by a third party beginning this year, with no fixed timeline for verifying Scope 3.

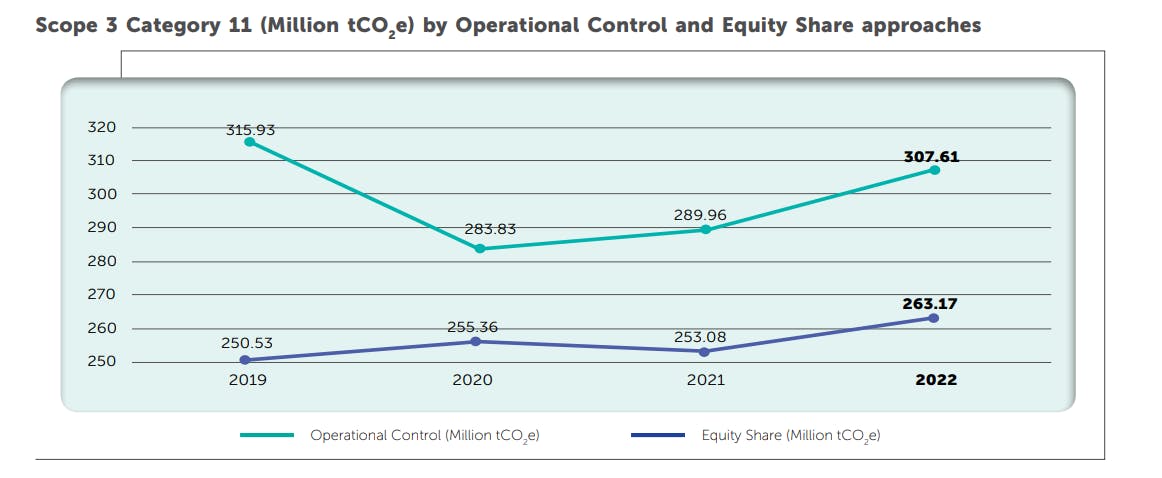

Petronas said that it has started to calculate and disclose its Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions for Category 11: Use of Sold Products. They attributed the increase in 2022 emissions to higher energy demand post-Covid 19. Image: Petronas Integrated Annual Report 2022

Petronas said in the same report, published in March, that it has “plans to validate its Scope 3 methodology and conduct external verification in subsequent years.” Representatives of the oil major in April said that the group was taking a “progressive” or “stepped” approach towards measuring Scope 3.

When asked by Eco-Business, however, Liza acknowledged that it was difficult for the company to commit to a timeline for reporting Scope 3 as it depends on when its partners are able to report their Scope 1 and 2. “When [we can do it] is not up to Petronas,” she said.

Reporting challenges

Petronas is not the only company struggling to secure accurate emissions data for Scope 3 reporting. “While most organisations can cover upstream emissions (from suppliers or vendors), collecting data for downstream emissions (from customers and product users) poses a significant challenge. This task requires extensive data on consumer product use and disposal,” said Komathi Mariyappan, director of climate advisory firm, Climate Era Consulting.

For practicality, organisations are advised to report third-party emissions beginning with their suppliers and vendors, and then to gradually extend their coverage to include client and consumer emissions in subsequent years, she told Eco-Business.

Based on the GHG Protocol Guidelines, there are several options to account for Scope 3 emissions. The preferred choice involves obtaining primary data directly from suppliers or vendors which corresponds to their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, said Komathi. An alternative is using secondary data from published sources. However, using industry average carbon emissions factors from studies or other databases risks yielding inaccurate results, she said.

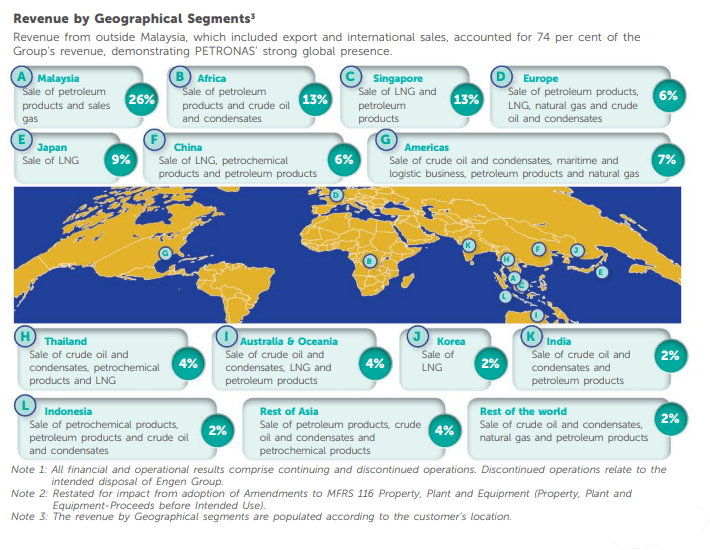

There is an additional geographic challenge to reporting the emissions of multinational corporations. Although some 70 per cent of Petronas’ production assets are located in Malaysia, its income by geographical region tells a different story: more than 70 per cent of Petronas’ revenue in 2022 came from outside Malaysia, with Singapore being the largest single-country buyer at 13 per cent. The neighbouring country has proposed to make reporting emissions mandatory for non-listed companies starting 2025.

Although the bulk of Petronas’ production takes place in Malaysia, its consumers are globally distributed, potentially increasing the challenges of reporting its downstream emissions. Image: Petronas Integrated Annual Report 2022

In Malaysia, there is no requirement yet for all companies to report their emissions. However, local stock exchange operator Bursa Malaysia has recently required that public-listed companies report their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, as well as a few categories under Scope 3, such as business travel, staff commuting and waste management, said Komathi.

“In the case of multinational corporations, it is common for companies to adhere to the sustainability mandates of their parent company or the country of origin. The parent company then extends these targets to its subsidiaries,” Komathi told Eco-Business, adding that Malaysian companies are often obliged to align with or support their parent company, without much room for alternative options.

Petronas is one of several large Malaysian corporations that have agreed to collaborate with stock exchange operator Bursa Malaysia to help drive the adoption of environmental, social and governance standards via Bursa’s Centralised Sustainability Intelligence Platform. The platform, which is being developed by Bursa in partnership with the London Stock Exchange Group, is aimed at enabling Malaysian corporations and their suppliers to calculate their carbon emissions impact.

Petronas has also signalled to its contractors in the oil and gas services and equipment industry that they need to start accounting for Scope 1 and 2 emissions, said chief executive officer Tengku Muhammad Taufik.

“We hope that with all the drives [to encourage emissions reporting] in Malaysia, insofar as making sure everyone is realising that they need to report and measure (emissions), that might hasten the journey (towards Scope 3 reporting for Petronas,” said Liza.

Greenwashing allegations

Petronas was the first Southeast Asian oil company to set a net-zero target, which it announced the pledge in October 2020. However, its Net Zero Carbon Emissions 2050 (NZCE) pathway sets emissions reduction targets only for only Scope 1 and 2, which at 47.9 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) pales in comparison to the 307 (MtCO2e) of Scope 3 emissions using the operational control approach, Rimbawatch highlighted.

“The fact that Scope 3 accounts for the majority of Petronas’s total emissions and that Petronas’s NZCE 2050 does not include plans to reduce Scope 3 emissions, are not communicated clearly by Petronas in their net-zero marketing materials,” the watchdog said.

Rimbawatch added that as a global oil and gas company and therefore a global polluter responsible for a significant share of the world’s emissions, Petronas should not be leaving Scope 3 out of its net-zero targets. “Petronas’ NZCE and associated marketing materials are exemplary of what the United Nations High-Level Expert Group has defined as greenwashing,” said Rimbawatch.

At the media dialogue, Petronas’ Taufik acknowledged the criticisms levelled against the company. “I know that the intent is pure. In fact, I laud the insights from these non-governmental organisations (NGOs),” he said. “But I think we need to engage in a more practical, open and realistic manner to actually have the solutions in place.”

Petronas’ answer to its Scope 1 and 2 emissions primarily hinges on its carbon capture and storage (CCS) initiatives, the most prominent of which is the Kasarawri CO2 Sequestration project offshore Sarawak, designed to sequester 3.3 million tonnes of emissions. Rimbawatch, however, pointed out that this represents just 0.9 per cent of Petronas’ total 2022 emissions.

“Wouldn’t re-directing the RM4.5 billion invested in the Kasawari project to the expansion of renewable energy capacity instead create more credible emissions reductions in Malaysia?” asked the watchdog.

Petronas has acknowledged that it needs to pivot towards renewable energy in the long run, but that its core business of hydrocarbon production is still needed for energy security. Last year, the oil company established a renewable energy arm, Gentari, which is pursuing opportunities in renewables, hydrogen and green mobility. But the group is still at an “investing stage” in renewables, said Taufik, and the operation has yet to generate significant enough earnings to attract potential partners.

“We already know consciously that in order to sustain Petronas, at some point we will transcend molecules, go into electrons, and become a superstore that has both,” said Taufik. “But that is a capital-intensive exercise.”

The company is also pursuing decarbonisation via “low-hanging fruit” like cutting methane emissions and improving energy efficiency. Petronas has previously invested in carbon credits via the Bursa Carbon Exchange, but paying for carbon offsets is viewed as a last resort, said Taufik.

“[Concerning] offsets, it’s a bit nebulous right now. We see challenges around accreditation of those credits beign applied uniformly,” he said, describe the carbon offset market as “a bit of a Wild West”.

[ad_2]

Source link