[ad_1]

An old cliché popularized by former President Bill Clinton says that Democrats want to fall in love with their political leaders while Republicans just fall in line. The chaos unfolding in the new Republican-controlled House shows that analysis, if it was ever true, certainly doesn’t hold today.

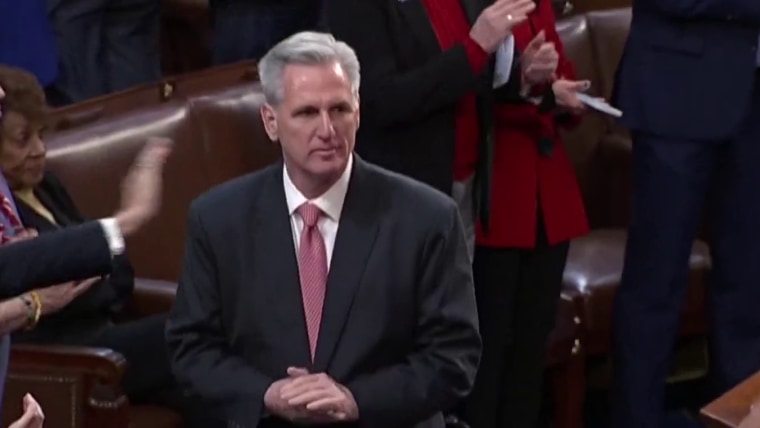

Since the new Congress began Tuesday, every time Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., has called a vote to be elected speaker, he has gotten no closer to the gavel. At the same time, his critics from the Republican Party’s right flank so far lack a viable alternative. People are becoming restless as the business of Congress is frozen. President Joe Biden has described the standoff as “embarrassing.”

The alternative is making deals behind closed doors, like the Democrats have done, preventing the public from having any insight into what’s being done

But the drama over the speakership is in many ways healthy, not dysfunctional or dangerous or inane or whatever else the critics call it. There are different schools of thought in the GOP, because it represents almost a third of the country — and it’s appropriate that the party have representatives of different factions competing to be the speaker rather than automatically operating in lockstep with power brokers.

That competition is best done out in the open. The alternative is making deals behind closed doors, like the Democrats have done, preventing the public from having any insight into what’s being done while neutralizing the leverage of party members who would like to see change.

Though there is no shortage of backroom deal-making going on among House Republicans, either, the public nature of the leadership fight means many of the concessions McCarthy is offering have been announced by his opponents. And the concessions themselves are a sign that dissenters can’t simply be steamrolled.

This process is part of an important ideological debate the GOP has been waging for decades over how far to the right to take the party. Much of the dispute over the speakership is about holding party leaders — who were too long afforded great deference — accountable to the will of the grassroots.

That doesn’t mean the Freedom Caucus and other legislative coalitions far to the right should determine the results — their demands aren’t always feasible or desirable or supported by anyone other than extremists. If they overreach, they risk an outcome that would set their constituents back even further.

But as crucial as it is for the House to eventually make a decision so it can proceed with important business, it’s a good thing that it’s not just a cakewalk for McCarthy. The point of representation in the legislature is to reflect the interests of different groups, not to increase the centralized power of the person at the top.

Large swaths of the conservative activist base have long expressed little faith in the GOP’s governing class, believing it is unserious about keeping campaign promises to control spending, repeal various liberal policies or secure the border. Instead of taking bold action that could upset the status quo, establishment Republicans are perceived to be more interested in protecting their jobs and ties to the elite.

As Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla., one of the leaders of the anti-McCarthy charge, told reporters Tuesday, there is “very little difference” between McCarthy and former Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.

This antagonism isn’t unique to McCarthy. The RealClearPolitics polling average finds Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky with a 23.3% favorability rating, to McCarthy’s 22.8%. This is among all voters, but it suggests a lot of GOP dissatisfaction, too.

“Mitch McConnell would much rather lose races than have America First senators in the Senate because he’s petty, he’s vindictive and he despises the base,” conservative advocate Ned Ryun told Fox News’ Tucker Carlson before the midterm elections. “He would prefer to be in the minority” than to see GOP candidates he dislikes succeed.

This tussle over the heart of the party has been going on for years, because the Republican leadership has failed to adequately respond to this criticism. Back in 1995, Newt Gingrich nudged aside longtime House Republican leader Bob Michel of Illinois to become the first Republican speaker of the House in 40 years after President George H.W. Bush raised taxes in violation of a campaign promise, helping fuel Gingrich’s rise. In less than four years, though, conservatives who thought Gingrich was getting too loose on spending helped push him out.

When Bush’s son George W. became president, his attempt to work with Democrats on immigration reform incensed many Republicans. That helped oust House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, in 2015 and then his successor, Paul Ryan, R-Wis., once a conservative darling.

Economic policy also played a role in the shakeups. The tea party, which a decade ago promoted a series of successful Republican primary challenges, adamantly opposed the bank bailouts begun under the younger Bush in the aftermath of the housing crisis. And there have been a series of federal spending plans, most recently the $1.7 trillion omnibus package, that have passed with Republican votes over conservative opposition.

The trust deficit between GOP leadership and conservatives might be the party’s most intractable problem. Can anyone close it?

Sometimes Republicans haven’t had the political power to do what the grassroots have asked. Sometimes they’ve simply broken their promises. And other times, as with the attempted repeal of Obamacare, it’s been a little of both.

In the face of these disappointments, disaffected conservatives have proven they can punish Republicans who don’t govern as they would like. At the same time, they don’t speak for all of the party, so they, too, face checks on their ambition. They also have less of a track record of governing effectively, which is rightly an impediment to their calling all the party shots.

Republicans talk a great deal about the federal budget deficit, especially when they are out of power. But the trust deficit between GOP leadership and conservatives might be the party’s most intractable problem. Can anyone close it? The answer is important not just to the right wing, but also to representative government.

[ad_2]

Source link