[ad_1]

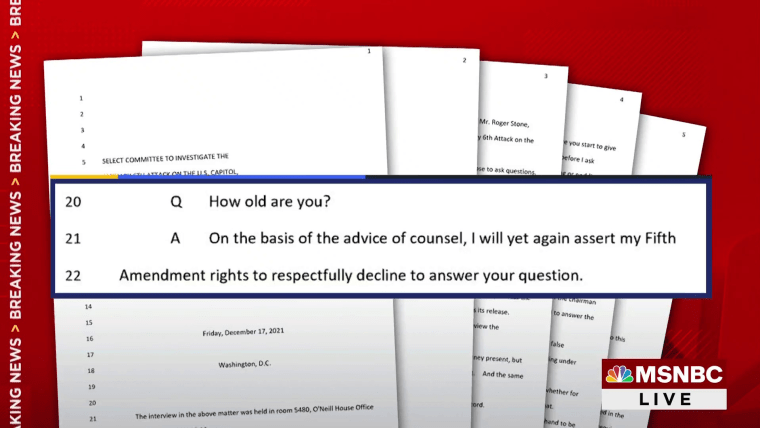

Following the release of dozens of transcripts, the public now knows that several advisers and associates of former President Donald Trump took the Fifth Amendment when questioned by members of the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. Political commentators have already suggested that pleading the Fifth confirms the guilt of these individuals. After all, as Trump himself once noted, “The mob takes the Fifth. If you’re innocent, why are you taking the Fifth Amendment?”

This erroneous perspective of the right against compelled self-incrimination forgets a lot of history.

Too many Americans believe that a person invokes the Fifth only when they are hiding something — usually criminal behavior. This erroneous perspective of the right against compelled self-incrimination forgets a lot of history and ignores the amendment’s true purpose. The right not to incriminate oneself, often called the “privilege,” traces its origins to the 12th century. The right became controversial in 15th and 16th century’s British proceedings when persons were summoned to testify about their religious or political beliefs. Persons compelled to testify invoked the Latin maxim nemo tenetur prodere se ipsum, meaning no one should be required to accuse himself.

In the 1950s, Sen. Joe McCarthy, R-Wisc., accused many persons, without proof, of being members of the Communist Party. At that time, being a communist was a crime. When these persons refused to testify before McCarthy’s Senate committee, he called them “Fifth Amendment Communists.” As a result of McCarthy’s actions, many politicians and even much of the public railed against the Fifth Amendment and wanted it abolished.

Over two decades later, in 1986, Sen. John Glenn, D-Ohio, criticized Lt. Col. Oliver North for invoking the Fifth during congressional hearings investigating the Iran-Contra scandal. “I can’t think of anything that is going to polarize Capitol Hill more or make this into a political football any more than people taking the Fifth or stonewalling it and preventing all the information from coming up,” he said. Despite Glenn’s ire, North legitimately invoked his constitutional right not to testify.

Finally, consider Lois Lerner’s 2013 experience before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. Lerner was the director of the Internal Revenue Service’s Tax-Exempt and Government Entities Division during the Obama administration. Lerner’s office had been accused of delaying the approval of applications from certain politically conservative groups. The inspector general of the Treasury Department eventually concluded that, while some employees working under Lerner had acted inappropriately, there was no evidence to support Republican congressional members accusations that Lerner’s office was motivated by political concerns. Nonetheless, Lerner was subpoenaed to testify before Congress.

On May 22, 2013, Lerner appeared before the committee. Lerner made an opening statement claiming her innocence. She then invoked the Fifth Amendment and refused to answer any questions from members of the committee.

Republican members of the committee were furious. They argued that by making an opening statement in which she professed her innocence, Lerner had waived her Fifth Amendment rights. Eventually, the committee voted to hold Lerner in contempt of Congress.

Top analysis related to the Jan. 6 investigation

Despite the indignation of Republican members of Congress, there was no inconsistency between Lerner stating that she had done nothing wrong and her taking the Fifth. Nor had Lerner waived her right to silence. Twelve years earlier, in Ohio v. Reiner, the Supreme Court stated: “[W]e have never held … that the privilege is unavailable to those who claim innocence. … [T]ruthful responses of an innocent witness, as well as those of a wrongdoer, may provide the government with incriminating evidence from the speaker’s own mouth.”

Yes, the Jan. 6 committee is not a criminal court, and the Supreme Court has ruled that an adverse inference of guilt can be drawn in civil proceedings when a witness invokes the Fifth. But the distinction between criminal and civil proceedings misses the point. The Fifth Amendment applies in any legal proceeding. (Trump invoked the privilege nearly 100 times during his 1990 divorce proceeding when questioned about “other women.”) And there is no inconsistency between claiming one’s innocence while invoking the Fifth, so said the Supreme Court in Reiner, when it noted that “the privilege protects the innocent as well as the guilty.”

And indeed, there are many perfectly legitimate reasons why people, including the individuals called to testify before the Jan. 6 committee, plead the Fifth. Most often it is because their lawyers advised them to do so. When testifying before Congress, a person might say something that could harm their legal interests in a criminal matter. The transcripts recently released reveal that congressional investigators had a lot of information regarding the activities and conversations of witnesses subpoenaed to testify. No competent lawyer would let his or her client to testify about matters that could later be used against the person in a criminal trial or be the basis for a perjury prosecution.

If Congress wants individuals to testify about what they knew or did before, during and after Jan. 6, 2021, it has means to obtain that information. Congress can go to federal court to ask that the witnesses be granted immunity. With an immunity grant, these witnesses can be compelled to answer congressional questions, knowing that their answers and any derivative evidence from their answers cannot be later used against them in a criminal trial. That’s the appropriate and constitutional way to proceed. Proceeding in this way, protects the Fifth Amendment rights of individuals and gives Congress the information it wants.

[ad_2]

Source link