[ad_1]

The name Chidester Stage Company may not have the ring to it that Wells Fargo or the Butterfield Stage has, but still it had much more import in Arkansas than either of the other two.

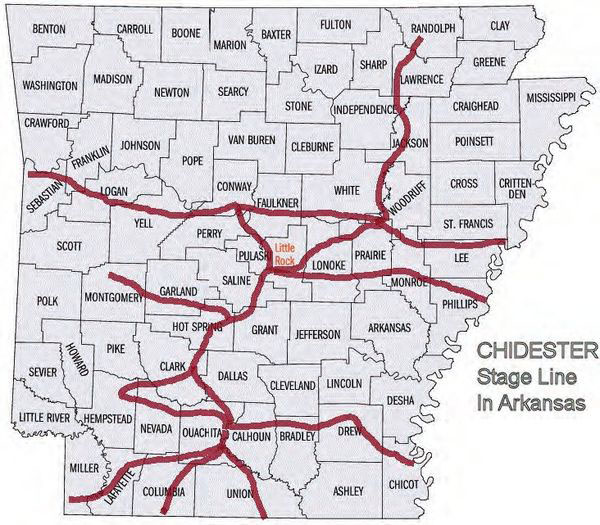

Chidester stages connected the small towns and villages across the state as feeder lines to the larger stages, as well as to river ports allowing long-distance travel.

John Chidester, a man with experience in freight and the handling of horses, arrived in Arkansas at just the right time. Mail routes, previously operated by the government, began contracting work to private companies during the 1850s.

Chidester arrived in Camden in 1857 and quickly saw the opportunities available to an enterprising gentleman. He began by obtaining the bid on the mail routes, a move that ensured his passenger business was profitable.

In 1858, he purchased the McCollum mansion in Camden and set up headquarters in the town. Chidester established an intricate web of stage routes with stages running to Hot Springs, Little Rock and over to Memphis. He sub-contracted with Butterfield Stage to establish the route from Memphis to Fort Smith. Butterfield’s northern stage route would then connect with the line into Fort Smith and continue west to California.

Other Chidester lines connected Magnolia, Pine Bluff and even ran into Texas and Louisiana. At its peak, the line employed 300 men, 2,000 horses, and 60 Concord wagons. His stages, pulled by four-horse teams set record travel times between towns and were noted for their efficiency.

John Ferguson’s diary described one of his journeys as, “delightful moonlight, run all night with some sleep, jostle, jolt, thump and bump. Arrived at Gaines Landing hot, wearied, tired, worn out, full of dirt and dust.”

During the Civil War, Chidester, a known Southern sympathizer, was suspected of pilfering through the mail on his stages to obtain state secrets which he supplied to the Confederacy.

In the spring of 1864, Federal troops occupied Camden. General Frederick Steele commandeered the Chidester home and used it for his headquarters during the engagement at Poison Springs. Later, hearing that Chidester had pilfered through the mail and obtained secrets, Union troops were sent back to the home to arrest Chidester.

Hearing of his eminent arrest, Chidester hid himself in a small upstairs closet. Union troops fired shots through several of the rooms and walls, unsuccessfully seeking to discover his hiding place. The holes in the walls still remain in the building today. Escaping, he fled to Texas where he remained for the duration of the war. He was later provided amnesty for his alleged war crimes.

After the war, Chidester established the country’s longest stage route. The line ran west from Camden, through Fort Worth and then on to Yuma, Ariz. The Camden house was the center of the Chidester empire, an empire run by a shrewd businessman who knew how to stay one step ahead of the expanding railroad system.

The Chidester mansion served as the central mail station for his expanding business. The horses and coaches were kept in a large two-story barn on the west side of the house. Two of the upstairs rooms were used for stage drivers and for overnight passengers traveling on the line.

Gradually, the railroads connected the various smaller towns serviced by the stage lines, the mail routes were taken over by the faster trains and stage service was no longer required.

Today, the beautiful Chidester mansion has been converted to a museum. The elegant furniture shipped in for use by the wealthy Chidester family still occupies rooms that also contain the photographs, books and jewelry owned by the family.

Leah Chidester’s china, silver, linens and even her 1851 sewing machine are still located in the home, all a memorial to the once powerful stage magnate that provided vital transportation needs in early Arkansas.

[ad_2]

Source link