[ad_1]

Sounds echoed throughout the building as workers scurried about preparing the fruits and vegetables for processing. Women talked among themselves, exchanging gossip and anecdotes while watching over their children, who were scurrying about underfoot.

Older children, though legally underage to work, were assisting their parents by peeling heated tomatoes, snipping of the ends of snap beans, or halving peaches. Parents were commonly paid by the number of cans produced so all help in providing extra income was appreciated.

By the early 1900s, most smaller towns in Arkansas had one or more canning factories which preserved and sold local produce.

Generally, a group of businessmen would put up money as loans to local banks who would then contract out buying the racks, trays and boilers and putting up a canning shed or building.

Initially, these were small-time operations where local families would work during harvest season to make extra money. Men generally received about 10 cents an hour for processing the produce, while women were paid by the bushel to prepare the tomatoes, beans or fruit.

The product would be poked through holes at the top of the can, water and salt were added, and then the can was patched with a piece of metal and soldered. The cans were then placed in a boiler where the product was cooked and harmful bacteria killed.

Some of the largest packing companies were found in Northwest Arkansas. In 1886, Springdale Canning became one of the first large commercial canneries. It employed up to 100 people during its busy season and contributed to the economy of the entire area by buying area products. By the 1930s, the Springdale plant could process as many as 3,500 cases of beans, greens, spinach or tomatoes in a 10-hour day.

Welch’s began a grape juice factory in 1923 to take advantage of the large area grape harvest and the Springdale area plant continued operating until 1978. Smaller towns like Ozark, Clarksville, Atkins, Lowell and Pettigrew had canning facilities that catered to one product, but they began to fade away as federal food regulations, coupled with expensive new technology, forced consolidation.

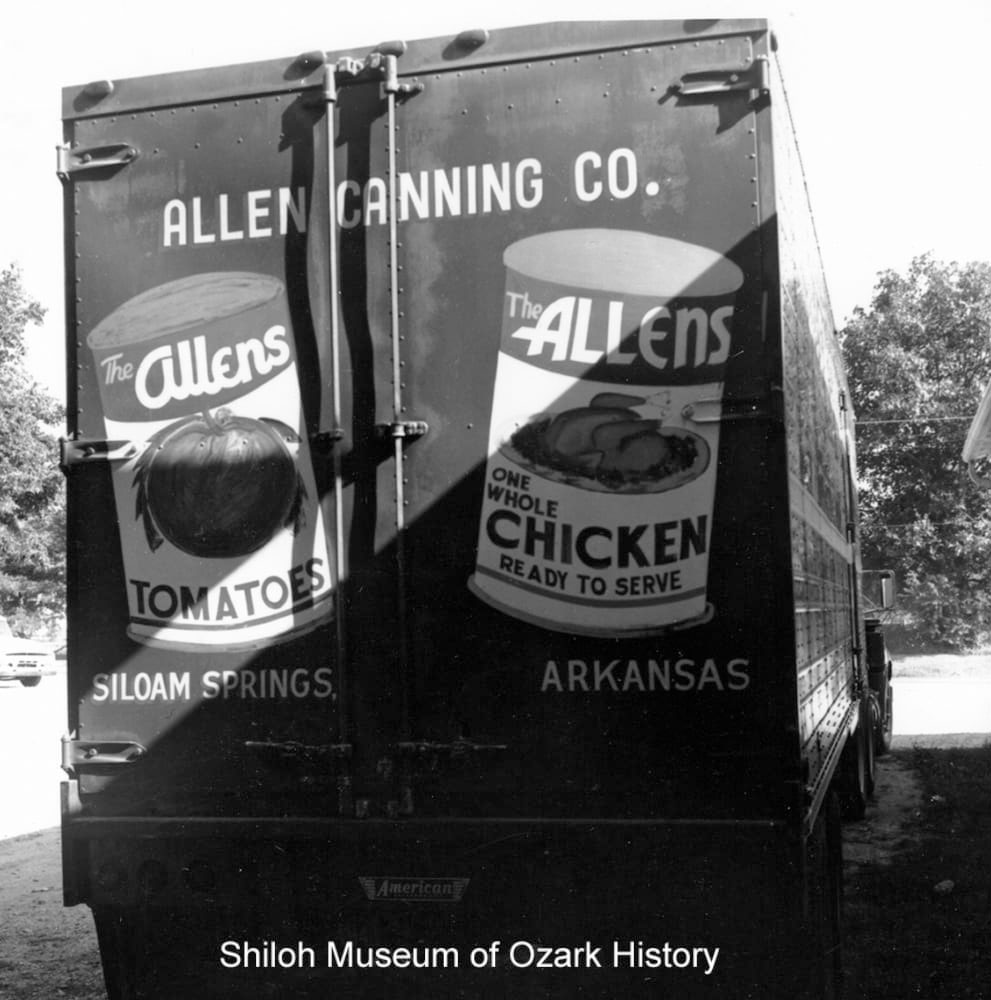

Two of the big names to emerge from the process was nationally known brands Atkins Pickle Company and the Allen Canning Company.

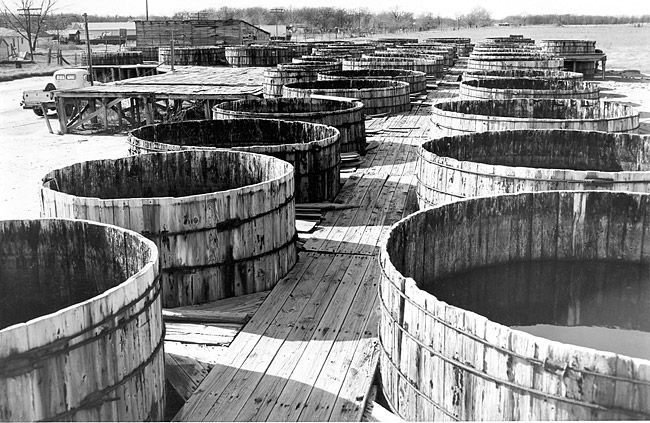

For more than 50 years, Atkins Pickles was the choice name brand in America. During its early years, the factory produced specialty items such as tomolives, pickled okra, peppers and onions, but eventually concentrated only on pickles.

In 1983, the plant employed 500 people and sales reached $40 million dollars. Visitors to the state capitol were given gift packs of Atkins products to showcase items produced in state. Several consolidations into national conglomerates later, an organization known as the Suiza Foods Corporation purchased the company and closed the Atkins brand.

Allens Incorporated began in Siloam Springs as a local canning company. In 1976, Allens was the world’s largest independent food processor and was one of the top ten canneries in the world. The company claimed the ability to pick the vegetables in the morning and have them ready to ship by night.

By 2013, Allens employed more than 1,000 people nationally and produced canned and frozen vegetables under 11 brand names. Alma laid claim to being the spinach capital of the world as a result of the spinach canned at the local Allens cannery under the brand name of Popeye spinach. A large statue of the character was erected as a symbol of the city.

Like other businesses that preceded it, Allens, Inc. suffered from declining markets and large corporate consolidation. After several sales to increasingly larger corporations, Allens closed its production unit and the business closed.

Passing through the small towns, one sees the empty enclosed plants, the boarded up windows, and the corporate “for sale” signs hanging on the fences. The jobs are gone, the young have moved on and the only noise within the canneries are the sounds of silence.

In 1976, Allens was the worlds largest independent food processor and was one of the top ten canneries in the world. (Courtesy photo)

In 1976, Allens was the worlds largest independent food processor and was one of the top ten canneries in the world. (Courtesy photo) Atkins Pickles waas the choice name brand in America for fifty years. In 1983, the plant employed 500 people and sales reached $40 million dollars. Visitors to the state capitol were given gift packs of Atkins products to showcase state-produced items. (Courtesy photo)

Atkins Pickles waas the choice name brand in America for fifty years. In 1983, the plant employed 500 people and sales reached $40 million dollars. Visitors to the state capitol were given gift packs of Atkins products to showcase state-produced items. (Courtesy photo) Initially, canning companies were small-time operations where local families would work during harvest season to make extra money. Men were paid by the hour and women were paid by the bushel to prepare the tomatoes, beans or fruit. (Photo of tomato pickers courtesy of Shiloh Museum of Ozark History)

Initially, canning companies were small-time operations where local families would work during harvest season to make extra money. Men were paid by the hour and women were paid by the bushel to prepare the tomatoes, beans or fruit. (Photo of tomato pickers courtesy of Shiloh Museum of Ozark History)[ad_2]

Source link