[ad_1]

In 2010, Katrina Cox was in Spain on what should have been a dream trip. She was chaperoning a group of her Arkansas high school students who were gleefully taking camel rides through the Iberian peninsula. But as she watched the teenagers – and even the other adults – spryly climb atop the massive animals, she knew it wouldn’t be possible for her.

Cox was overweight. She considered her next move with a mix of horror and embarrassment. “I just didn’t know how I was going to get my butt up there,” she remembers with a chuckle. “I missed out on that adventure.”

But that was 88 pounds ago.

Cox, now 65, is part of a growing cohort of people who have lost dramatic amounts of weight taking a new class of drugs called GLP-1s for short. They help users regulate blood glucose levels and delay gastric emptying, decreasing appetite and promoting weight loss. Officially, in drug company studies, patients lost up to 26% of their body weight. Anecdotally, in social media groups, they’re heralded as “life changing” and “a miracle.”

“All of a sudden riding in an airplane was 10 times better,” Cox says. “I went to Alaska and I rode in a little tiny plane. I went whitewater rafting with no hesitation. I’m just out doing all kinds of physical activities.”

Cox’s story will sound familiar to anyone who has struggled with weight. She says she tried seemingly every diet for 30 years and finally accepted she was overweight.

But now, after taking these new medications, she’s at a healthy weight. And at 65 years old, Cox says she feels like she’s 40. Her energy is up, her mobility is up. And one of the things she’s most excited to do – travel.

“It will help me fulfill my retirement travel dream,” she says. She has a few major trips and a few smaller ones planned for this year. “It’s like freedom.”

Enter BigPharma

Globally, humans started getting bigger and heavier in the 1970s with the rise of ultra-processed foods and fast food. Since 1975, global obesity rates have nearly tripled.

But it hasn’t been without a fight. In the United States, overweight Americans desperate for options spend more than $70 billion each year on diets and other weight-loss treatments.

In the 1980s and 90s, companies like Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig flourished. At the turn of the century, books like Atkins and the South Beach Diet became best sellers.

But for most people, diets usually fail. Over half the world wide population will be overweight or obese by 2035, according to the WHO. There haven’t been any significant mainstream advances in weight management for 50 years – until now.

The Most Profitable Pharmaceuticals in History

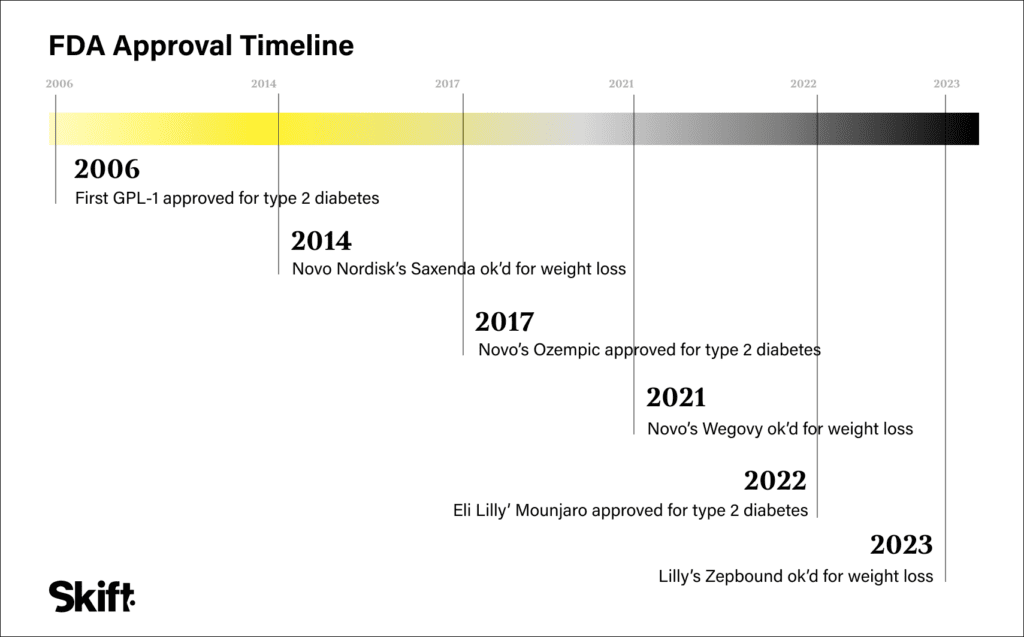

The first GLP-1 was approved by the FDA in 2005 for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. It wasn’t until 2014 that Novo Nordisk released an injectable medication specifically dedicated to weight loss. Novo and Eli Lilly now have weight loss indications for their diabetes drugs Ozempic and Mounjaro, which are also blockbusters. They’re also being studied to treat various other conditions, such as heart disease, alcohol addiction, and Alzheimers.

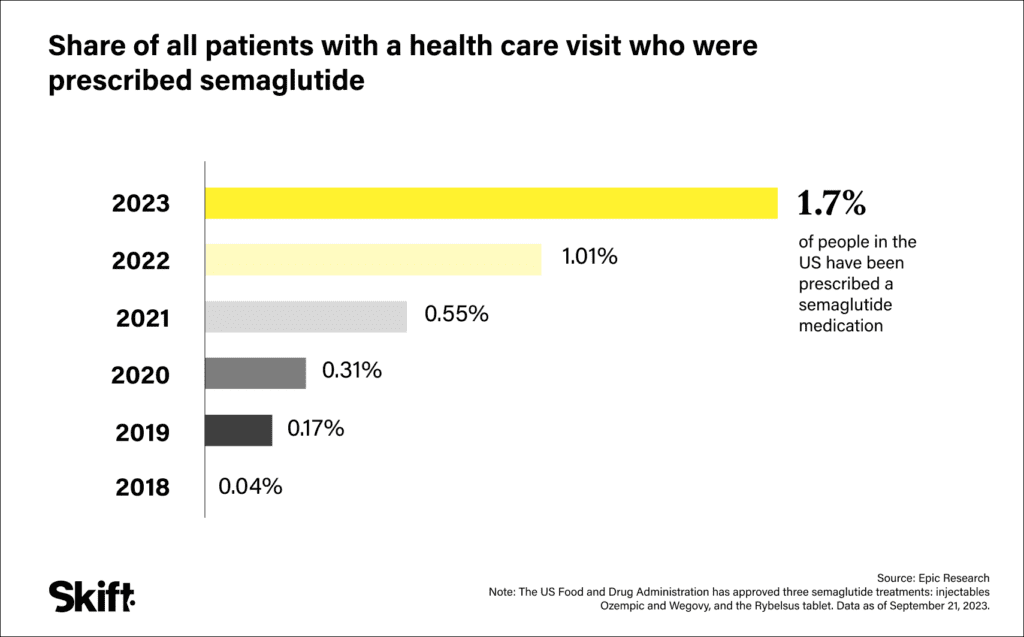

With each iteration, these drugs keep getting better and more effective. Doctors are fielding questions from patients about them non-stop with prescriptions for GLP-1 medications increasing 300% from 2020-2022, according to Trilliant Health.

Goldman Sachs sees a $100 billion market by 2030. That puts GLP-1s on track to be the most profitable class of pharmaceuticals in history.

Tourism Winners and Losers

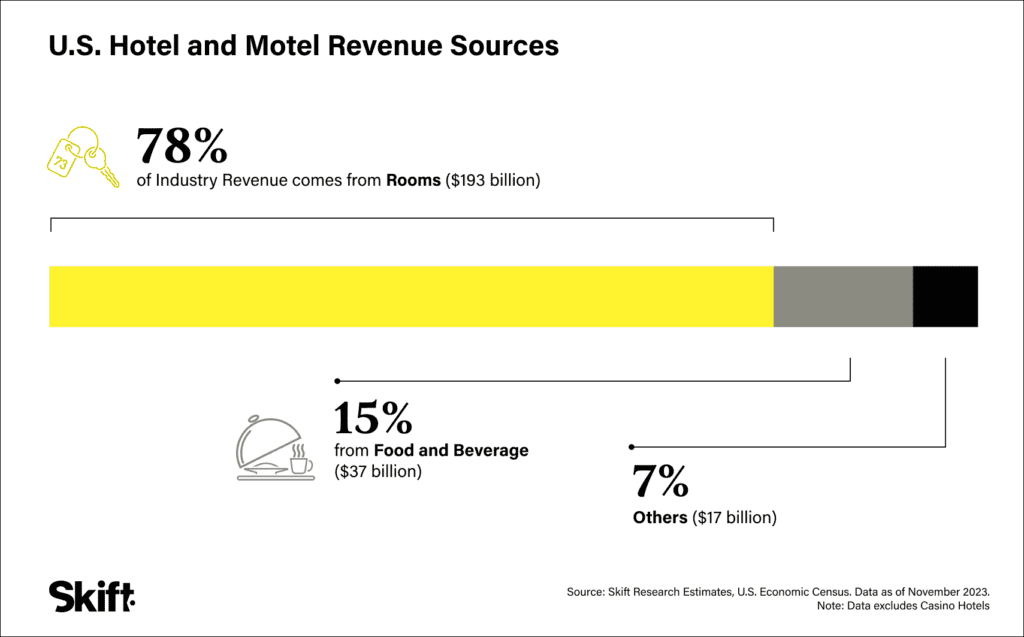

Large companies like Walmart and Conagra say they are already looking at what impact GLP-1s will have on business. For the travel sector, the winners will be those that have food and beverage as a cost. Losers will be those that have it as a revenue generator.

That means the Ozempic Era could be good for airlines, all-inclusive resorts, cruises, experience providers and tour operators. It might be bad for theme parks, hotels, movie theaters, and entertainment venues that rely on food, drinks and concessions.

Take airlines. The more an aircraft weighs – including human passengers – the more fuel it takes to fly it. Fuel sometimes comes in as the airline’s largest expense, often about equal to labor, depending on the airline.

Historically, airlines have been almost comically ruthless when it comes to eliminating excess weight. Seats have become much lighter over time.

They ditched bulky paper manuals for lighter digital ones. And decreased the number of heavy beverage carts. American Airlines famously removed one olive from its dinner salads, trimming both physical weight and reducing the cost of the ingredients.

“If the average passenger lost 10 pounds, this would trim 1,790 pounds from every United flight, implying a savings of 27.6 million gallons a year. At an average 2023 fuel price of $2.89 a gallon, United would save $80 million a year,” Bloomberg reported, citing Jefferies Senior Equity Research Analyst and managing director Sheila Kahyaoglu. “This benefit should be recognized similarly across airlines,” Kahyaoglu wrote. United told Skift it had seen the Jefferies report, but didn’t have a comment.

Experience providers and tour operators will benefit from vacationers losing weight. And it’s already happening.

In 2023, TripAdvisor’s Viator found U.S. bookings for its activities that require above-average physical exertion far outpaced those in 2022. Nature walk excursions were up 55%. Bike tours rose 46% and there was a 52% boost in hiking and camping trips. Skift Research predicts adventure tour operators could make an additional $1.3 billion in revenue because of GLP-1s.

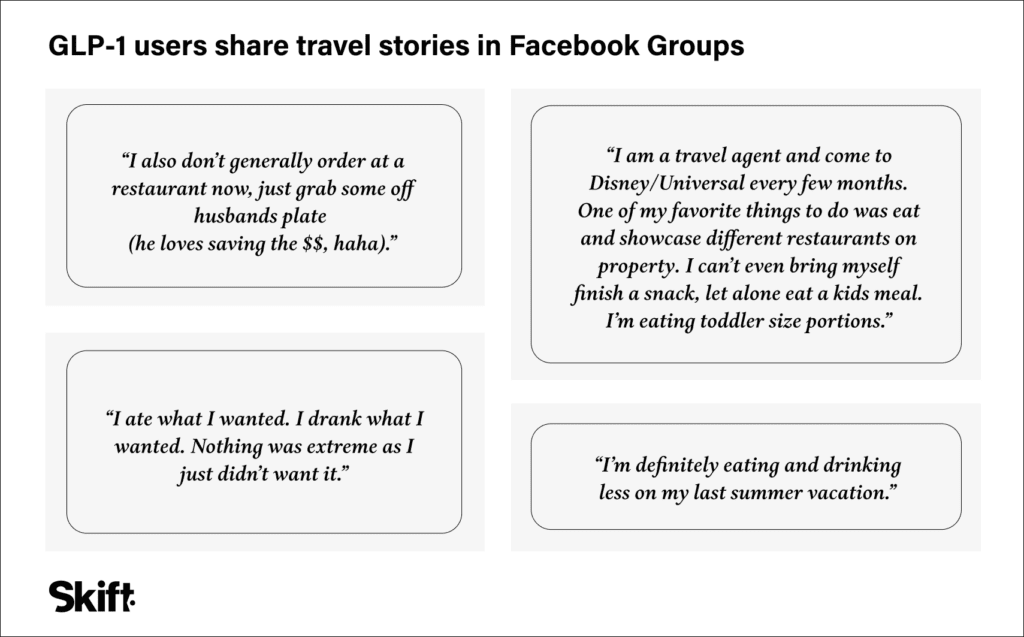

In social media groups where users swap before-and-after photos, they also eagerly post about upcoming travel plans. “I can not wait to take our next vacation,” one user wrote on Facebook. “Last year there were several things I couldn’t do with my children because of my weight – zip line, water slide, and go-karts. I’ve lost 58 pounds now and hope for 20 more.”

Those zipline and go-kart operators may indeed see a stream of newly svelte customers walking through their doors.

Largely, a healthier public benefits the travel ecosystem. But there could be losers.

Restaurants may be one of the most at-risk industries. According to Jefferies, a similar fate may befall alcohol producers, suppliers and distributors, as users of GLP-1s report less of a desire to drink.

Many U.S. consumers wait for travel as an opportunity to splurge on dining out. 13% of all U.S. restaurant spending happens while on vacation, according to Skift Research. That’s a staggering $108 billion each year.

If these medications cause only a 1% decrease in spending on food and drinks while traveling, that’s a $1 billion in the U.S. alone. This could be a huge opportunity. For instance, a traveler on Ozempic might choose to spring for an upgraded airline seat using the savings from a lower restaurant bill.

Katrina Cox, the retired teacher from Arkansas, is using the money saved from sharing meals with her husband for more activities.

“We did a little splurging on that plane ride,” Cox says, describing an excursion she took with her husband to the top of an iceberg – something she says she wouldn’t have done before taking weight loss medications. “We just breathed that beautiful mountain air. And it’s not cheap, that kind of thing. But you can do more of that if you’re not spending as much in the restaurant.”

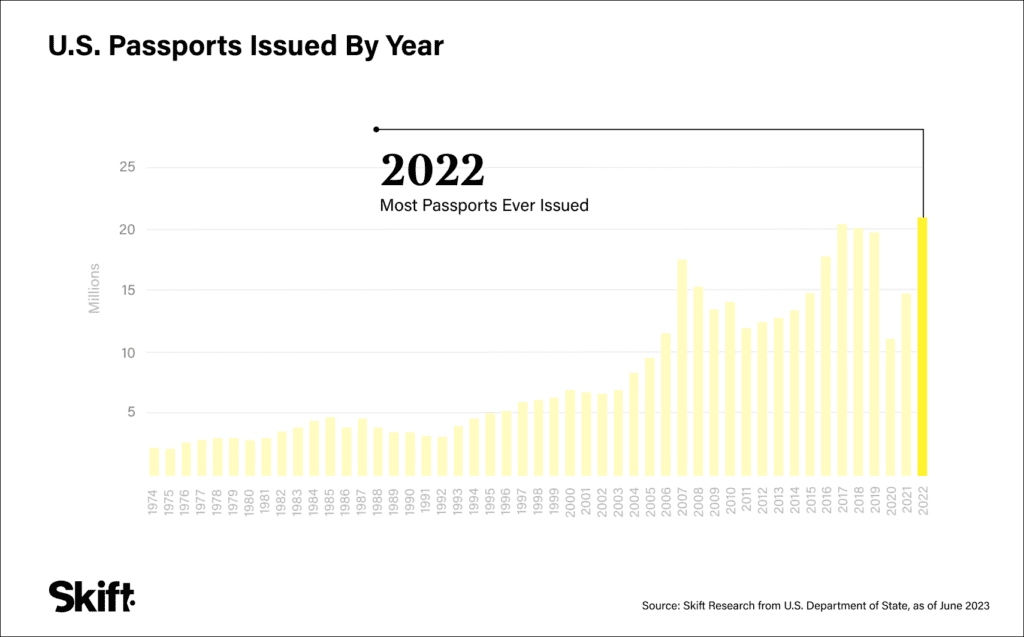

Other downstream effects may seem less obvious, but may, nonetheless, cause significant ripples on the travel ecosystem. Take passports. The U.S. government had an unprecedented number of applications in 2023, issuing more than 24 million passports in the last fiscal year. That’s more than ever before in U.S. history.

For adults, passports need to be renewed every 10 years – unless your appearance has significantly changed. One may need a new passport if weight loss is listed as a criterion.

“Identity management is important for security screening. TSA officers can recognize small changes in a person’s appearance,” said a TSA spokesperson in an email to Skift. “However, passengers have a responsibility to ensure that their ID photo is a generally accurate representation of their image.”

The weight loss achieved is often not ‘minor’ for the population these drugs are meant to serve. What happens when a large number of travelers need to update their passport due to a major weight loss? The State Department, the agency tasked with passport control, is already handling record numbers of documents. So the math is daunting.

Estimates suggest that 48% of the U.S. population possesses a passport. If 15 million Americans are taking GLP-1s by 2030, if even 5% of those people traveling need to reprocess their passport because of weight loss, that adds an additional 350,000 more passports into the processing queue.

The State Department didn’t respond to Skift’s request for comment.

What’s Next

The societal shift from these new medications is still in its infancy. Only 1.7% of Americans use GLP-1s, while over 40% of Americans are overweight or obese. Goldman bases its $100 billion prediction on only 13% of the qualifying population using the medications. The opportunity is massive.

Still, consumers have intense barriers to getting these medications. They’re expensive – over $1,000 per month in the United States. Insurance coverage is spotty, with many plans containing exclusions specifically for weight loss drugs. But, despite this, demand is so strong some of the medications are on the FDA shortage list.

As more countries approve and insurance covers costs, there will be a mainstream explosion that changes consumer behaviors. Most travel organizations Skift spoke to for this piece were not thinking about it yet.

But that’s not so for Katrina Cox. “I believe that it’s going to just change everything,” Cox says. “I’m just always planning the next trip because I feel so dang good.”

Credit:

Graphics by Vonn Orland Leynes

[ad_2]

Source link