[ad_1]

Decades before Iceman came out as gay or Robin first kissed his boyfriend, LGBTQ artists were creating queer comics in the 1970s and ‘80s. They weren’t working for Marvel or DC, though: They were making underground comic books, strips and zines out of their homes, DIY-style.

Premiering Monday on PBS, the documentary “No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics” shines a spotlight on some of these trailblazers, including Alison Bechdel (“Dykes to Watch Out For”), Howard Cruse (“Wendel,” “Stuck Rubber Baby”), Jennifer Camper (“Rude Girls and Dangerous Women”) and Rupert Kinnard (“B.B. and the Diva,” “Cathartic Comics”).

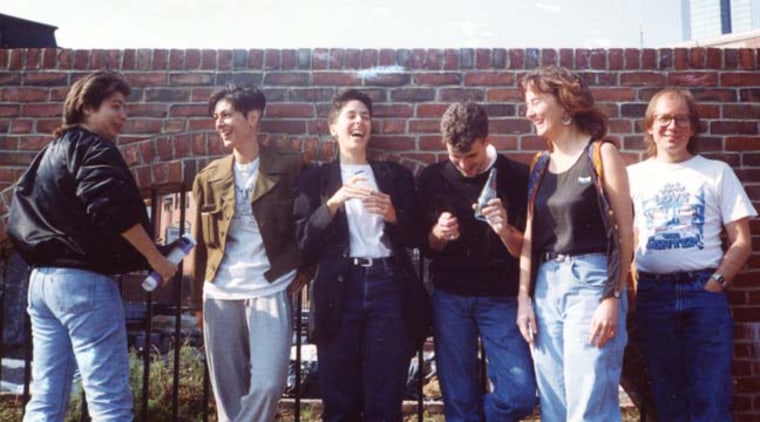

Joan Hilte and Howard Cruse at an OutWrite conference.Independent Lens

“No Straight Lines” also profiles Mary Wings, who is credited with publishing the first known queer comic book, “Come Out Comics,” in 1973.

“There’s a history of erotic illustrations, like Tom of Finland, and gag strips in the Advocate, but ‘Come Out Comix’ was the first ‘literary’ queer comic,” said Justin Hall, who produced “No Straight Lines” and is chair of the graduate comics program at California College of the Arts.

“Mary was the first interview we did,” Hall said. “She created ‘Come Out Comix’ in the basement of a radical women’s karate cooperative in Oregon, making this thing on a photocopier and distributing it through mail order.”

The autobiographical book, completed in just a week, chronicles a young woman’s realization of her sexual identity and her first fumbling romantic relationship.

San Francisco, where Wings now lives, was home to many of the earliest LGBTQ comic books and strips — most of which were made by queer women.

After Wings’ book came Roberta Gregory’s “Dynamite Damsels” in 1975, a series of humorous vignettes about the lives of lesbian feminist activists, and then Lee Marrs’ “The Further Fattening Adventures of Pudge, Girl Blimp” in 1977, about a 17-year-old runaway who arrives in San Francisco looking to lose her virginity.

Trina Robbins, a straight ally, arrived in the Bay Area in 1970. Two years later she wrote “Sandy Comes Out,” considered the first comic strip about an out lesbian, in “Wimmen’s Comix” #1.

Hall curated an exhibit of early LGBTQ comics for San Francisco’s Cartoon Art Museum in 2006, then worked on the graphic anthology “No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics,” published by Fantagraphics Books in 2012.

He filmed interviews for the book with the idea of creating a documentary and eventually brought in veteran documentary filmmaker Vivian Kleiman (“Families Are Forever,” “Always My Son”) to direct the project.

“I’ve been obsessed with comics since I was a kid; it’s how I learned to read,” said Hall, whose own work includes the comics “True Travel Tales” and “Hard to Swallow.” “I always knew I wanted to be involved somehow in creating comics. It was a phase I never grew out of.”

Graphic storytelling has particular appeal to LGBTQ creators, he added.

“It’s both a storytelling and visual art form, which I think is very powerful,” Hall said. “There’s a great quote from Alison Bechdel, who said she started making comics because she wanted to make lesbians visible.”

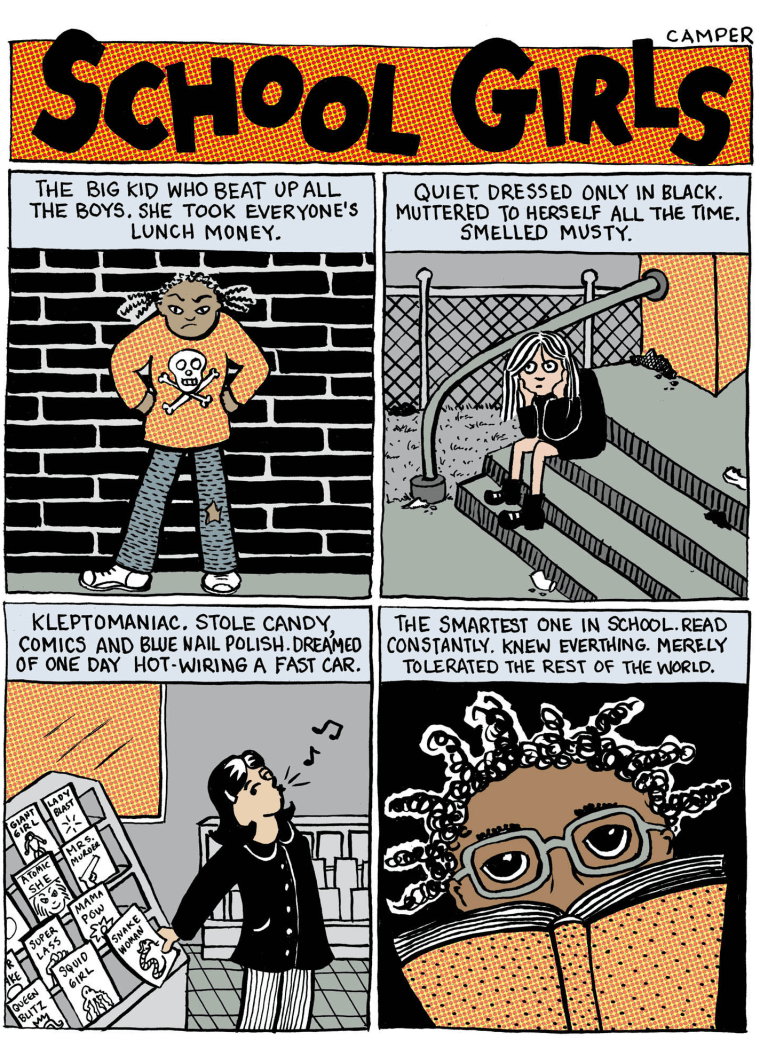

It’s also an art form that’s more available to marginalized groups, cartoonist Jennifer Camper said, and advances in technology have made creating and distributing comics cheaper than ever.

“You don’t need a lot of resources or buy-in from gatekeepers,” Camper, one of the comic creators featured in the film, added. “For people who want to tackle content that might not be approved by the mainstream, that’s very attractive.”

For queer readers, she said, reading comics “is very intimate.”

“You’re taking words and pictures and combining them in your mind to create things like time and motion — and carving out this universe for yourself,” Camper said. “It’s something you do privately, maybe even in secret.”

Camper has been creating comics since the 1980s, often reflecting on her experiences as both a lesbian and a Lebanese American woman. She has drawn strips for numerous LGBTQ newspapers and was a contributor to “Gay Comix,” a seminal anthology series that launched in 1980.

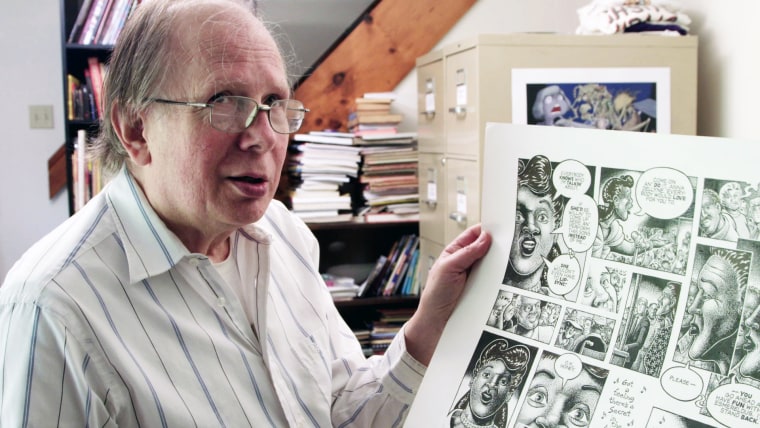

Howard Cruse, another cartoonist featured in the film, was the founder editor of “Gay Comix.” The strips in the series could be sexually frank, but they focused more on humor and drama than titillation.

Cruse also published “Wendel,” a strip that appeared in the Advocate throughout the 1980s. It followed a young gay man and his friends in the Reagan-Bush era, touching on same-sex relationships, gay bashing, HIV/AIDS and other hot-button issues.

His 1995 graphic novel, “Stuck Rubber Baby,” was about a young gay man coming of age in the South amid the civil rights movement. “Stuck Rubber Baby” was one of the first queer comics to get mainstream critical acclaim. (The book’s introduction was written by Pulitzer-winning playwright Tony Kushner.)

“Sometimes you don’t want to meet your heroes but, in Howard’s case, he was as beautiful as his work,” Hall said. “He was the godfather of queer comics. His generosity of spirit and intellect brought this community together.”

Cruse died of cancer in 2019, while “No Straight Lines” was still in development. Hall and Kleiman said his passing was the fuel that helped them push the project over the finish line.

“Vivian and I were at a low point, wondering if we’d ever get the movie made,” Hall said. “When Howard died, we were like, “We have to do it. It has to be done. He was one of the greatest artists of his generation, and he never got his due.’”

Over the past decade, queer comic creators have been getting increased recognition, if not fully getting their due. A 25th anniversary edition of Cruse’s “Stuck Rubber Baby” was released in 2020. Alison Bechdel received a MacArthur “genius grant” in 2014, and then her bestselling graphic memoir, “Fun Home,” was turned into a Tony-winning musical the following year. And just this month, Edmund White’s gay classic “A Boy’s Own Story” was released as a graphic novel.

But even as gains have been made, some things have been lost since the heady days chronicled in “No Straight Lines.”

“There was a period where every major city in America had an LGBTQ newspaper, and that’s where a lot of us were published,” Camper said. “We created this world that allowed us to get our work out there. There was less money, but there was a joy in creating things on our own terms.”

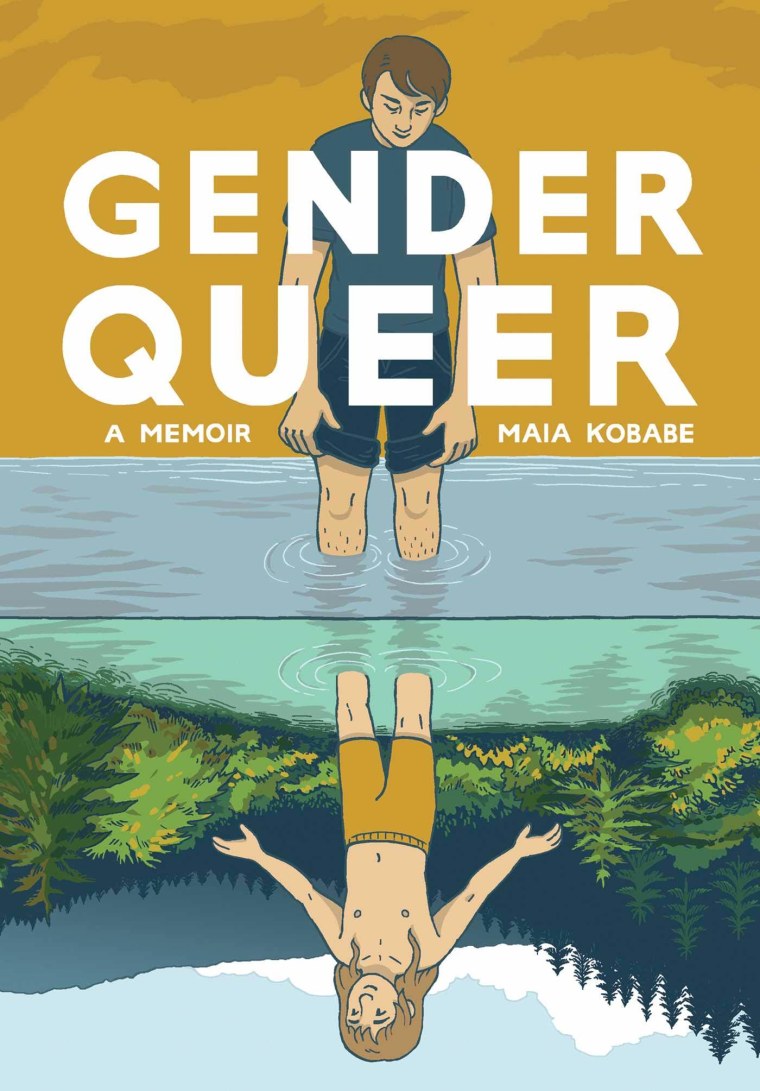

The attention queer comics now receive has also meant more scrutiny from conservatives: “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” a 2019 illustrated memoir by nonbinary artist Maia Kobabe, topped the American Library Association’s 2021 list of most challenged books in the U.S.

“For a long time, queer comics existed in this parallel universe,” Hall said. “Now we have comics for young queer audiences, and all-ages and YA books with queer characters, which is wonderful. But right-wing culture warriors are weaponizing these books.”

Camper said she misses the freedom and sense of community she felt in the 1980s.

“But there is a whole generation coming up now who understands, ‘Yes, comics are an art form and, yes, some comics have queer characters,” she added. “It’s very exciting.”

“No Straight Lines” premieres on PBS’ “Independent Lens” Monday at 10 p.m. ET, when it will also be available to stream on the PBS video app.

[ad_2]

Source link