[ad_1]

Copper is an appealing commodity for criminals, and in South Africa, they are cashing in — and almost everyone else is paying the price.

Copper is conducive to criminality because it can be recycled many times without loss of performance, and South Africa’s scrapyards offer an ideal conduit to launder the material.

Its ubiquity provides opportunities galore for thieves — copper cable is literally low-hanging fruit, often dangling in insecure locations, waiting to be plucked. And its distinctive red colour makes it easy for criminals to identify the metal.

The upshot of all of this in crime-ravaged South Africa, with its glaring rates of unemployment and inequality, is a tsunami of copper cable theft that is sweeping across a frail economic landscape, with disastrous consequences for businesses, households and public services.

“Every day in South Africa, criminal elements strip copper from wherever they can find it, including roads, homes, construction sites and mines. The theft of copper from already ailing infrastructure severely affects the capacity and operations of state-owned entities and municipalities,” says a new report — South Africa’s Illicit Copper Economy — by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime.

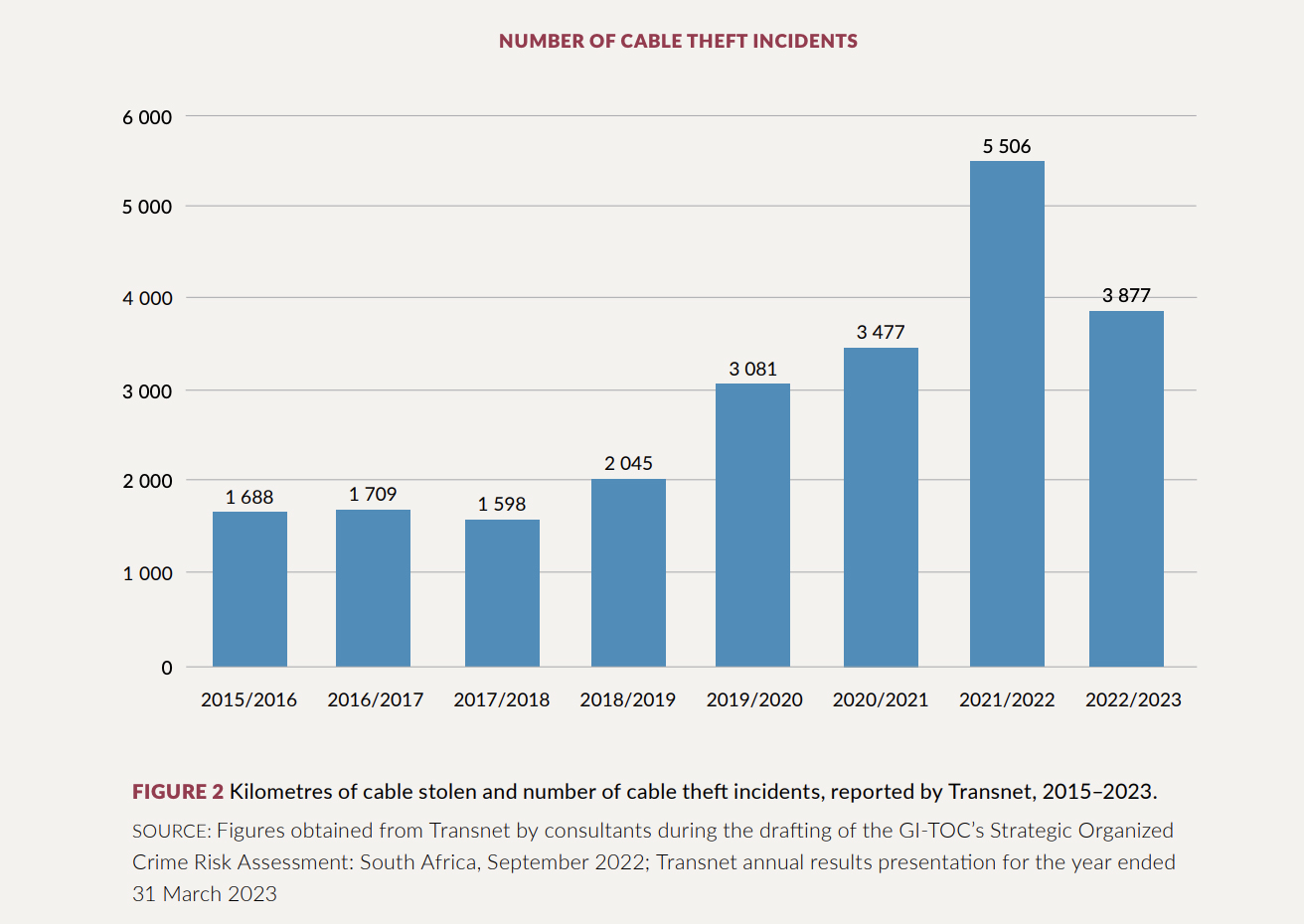

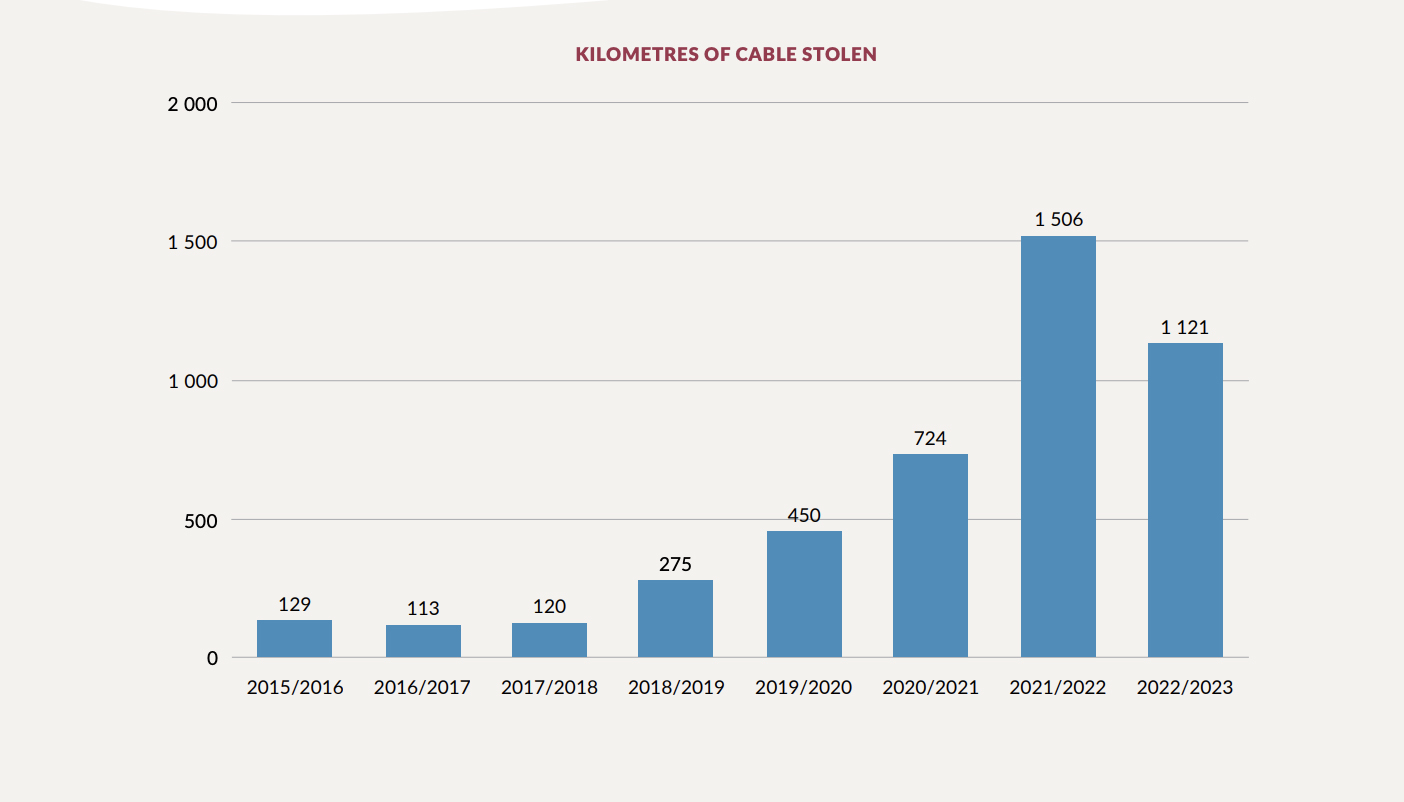

The report says that Transnet, Prasa and Eskom reported almost 11,000 incidents per year (italics added) from 2018 to 2022, and this number would swell if municipalities were included. And that’s just the public sector. Transnet and Prasa have been plundered of 30,000 kilometres of infrastructure — equal to three-quarters of the Earth’s circumference around the equator.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Copper theft from parastatals and municipalities estimated at R46.5bn, says Minister Patel

But from March 2019 to March 2022, the report says only 1,200 suspected copper cable thieves were arrested with 580 cases brought to court. Convictions numbered only 40. The report notes that “this low conviction rate could also be linked to trial delays and court backlogs”. Or perhaps the 40 convicted were just the dumbest copper cable thieves out there.

Soaring costs

And while the conviction rate is paltry, the economic costs are soaring.

“In 2021, state-owned enterprises Eskom, Transnet and the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (Prasa) and partially state-owned company Telkom said they were experiencing combined direct losses of about R7-billion a year, with an estimated R187-billion in associated losses to the broader economy, due to copper cable theft and vandalism,” the report says.

That figure does not sound far-fetched. A World Bank report recently said that crime cost South Africa’s economy the equivalent of about 10% of its GDP, or R700-billion, each year — and copper cable theft plays a starring role on this stage.

Read more in Daily Maverick: SA’s crime rate exacts a huge toll on the economy, says World Bank

The toll on the wider economy is far-reaching. It includes replacement and security costs, production losses, and power and logistics disruptions. Tens of billions of rand per year in coal and iron ore exports have been lost in part because of the theft of copper cable on Transnet’s shoddy lines, leading to production cuts. The ripple effects surge through the economy like electricity through a copper cable, with shocking results.

Diversified metals producer Sibanye-Stillwater lost more than R1bn in production in 2022 to copper cable theft, with another R1-billion spent on security. That’s how it all adds up.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Copper cable theft cost Sibanye ‘north of R1bn’ in production in 2022, mining forum told

Criminal efficiency

The report takes a deep dive into the illicit copper chain. Over R10-billion worth of copper scrap is legally traded in South Africa each year, with about 13% exported to other countries. But much of this is likely tainted.

“The high price and demand for recycled copper, coupled with the ease with which the metal is reprocessed, makes it a lucrative business for legitimate traders as well as criminal operations. Once acquired, stolen copper can be passed on to scrap dealers, who either repackage it for resale or melt it down, for distribution either on the legitimate market or on the black market,” the report says.

“Because stolen copper that is laundered back into the legitimate market is reprocessed, it is extremely difficult to trace or even detect. There are allegations that some scrap metal dealers go so far as to tender or quote to supply copper on the legitimate market, and then commission thieves to acquire the quantity needed to meet their requirements.”

So you get a legitimate contract, and then sub-contract to thieves to obtain the material, setting in motion the laundering process.

The syndicates involved are highly sophisticated and employ military-style operations, though there are also fly-by-night criminals involved.

“The first link in the illicit copper value chain is the people involved in the actual theft. This group takes the greatest risk for the least reward, and there are two categories. The first involves petty criminals who steal copper to eke out a living or sustain substance addiction,” the report says.

They use basic tools and steal small amounts at a time, usually from municipal sub-stations.

The other category in this chain “includes more sophisticated groups of between 10 to 30 people, working as independent contractors or as part of organised networks or syndicates”.

The second level comprises informal and small-scale scrap metal dealers — the “matchmakers” of the illicit copper market.

Moving up the chain to the third level, one finds larger recyclers, mills and exporters of scrap metal.

“The final link in the chain is the international groups that receive or purchase the stolen copper,” the report says.

This pyramid of predation in many ways mirrors the production and supply chains of the illicit gold economy — and these twin scourges have overlapping linkages — with the Zama Zamas on the bottom and international buyers at the top.

To address this challenge, the government has among other things imposed a temporary ban on scrap metal exports, with limited success in curbing copper cable theft. Initially in force for six months in 2022, it has been extended a number of times and now looks set to remain in place until the middle of 2024.

The report makes some sensible recommendations including the targeting of those at the top of this food chain.

“There needs to be a concerted effort by the SAPS and municipalities to close down informal scrap metal traders and bucket shops. The SAPS needs to establish a central electronic database of registered dealers,” the report recommends.

“A relatively quick and easy win would be to address the mislabelling of scrap copper as raw copper. The Trade and Industry Policy Strategies recommendation that raw copper exports should only be permitted if they are certified by a South African copper mine should be implemented. Mines should provide a copy of the certification to both SARS and the police to ensure coordination at the ports,” is another sensible proposal. DM

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link