[ad_1]

WASHINGTON — When the House returns Tuesday, Speaker Kevin McCarthy will confront a series of legislative deadlines and intraparty conflicts that have been bubbling up for months, raising fears of a government shutdown when money expires on Sept. 30.

The issues — from government funding and aid for Ukraine to a potential impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden — are significant individual challenges. Taken together, they amount to a daunting Rubik’s Cube for McCarthy, R-Calif., who must align a host of competing interests. He has little time, a paper-thin majority and a Democratic-led Senate and White House that are ready to play legislative whack-a-mole against right-wing priorities.

Looming over the end-of-the-month deadline is that some right-leaning Republicans insist McCarthy’s job isn’t safe if they don’t get what they want.

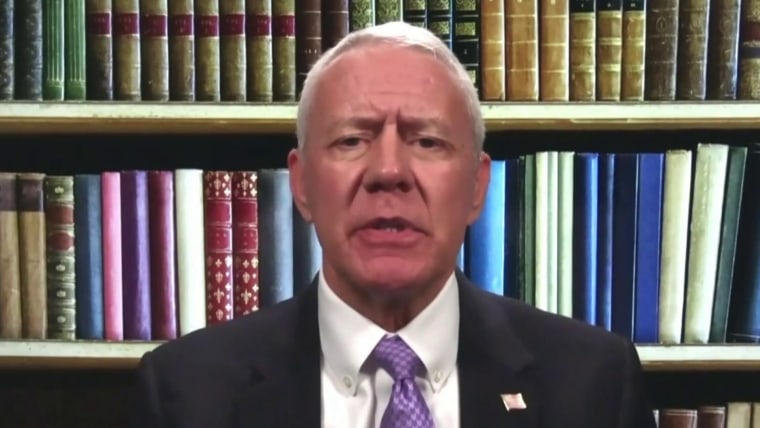

“There’s a perfect storm brewing in the House in the near future, in September,” Rep. Ken Buck, R-Colo., a member of the hard-right Freedom Caucus, told MSNBC’s Jen Psaki in an interview Sunday.

“On the one hand, we’ve got to pass a [short-term funding bill]. And we also have the impeachment issue. And we also have members of the House, led by my good friend, Chip Roy, who are concerned about policy issues,” Buck said. “So you take those three things put together, and Kevin McCarthy, the speaker, has made promises on each of those issues to different groups. And now it is all coming due at the same time.”

Roy, R-Texas, is also a member of the Freedom Caucus.

Here’s a rundown of the competing interests McCarthy will have to address.

Conservative spending demands

Right-wing Republicans are still angry about the two-year budget agreement McCarthy struck with Biden in the spring. They insist on cutting spending below those levels and adding conservative policy provisions on immigration and rolling back Biden’s agenda.

McCarthy has greenlighted that approach in the House, but it’s sure to hit a wall because Senate GOP leaders have made it clear the House’s partisan path won’t pass the upper chamber. Yet that may not be enough to persuade McCarthy’s right flank: They’re even pushing back against a short-term funding bill to extend the Sept. 30 deadline, and they say McCarthy’s best course would be to listen to them.

“When Kevin works with us to sit down to achieve conservative aims and get 218 Republican votes, we’ve been successful. That’s my advice to him,” Roy told reporters Monday. “Senate Republicans have never found a fight they want to shy away from. I think they should actually stand up.”

Rep. Ralph Norman, R-S.C., said the right feels betrayed by McCarthy’s budget deal with Biden and wants to undo it in spending bills.

“What he surrendered — that’s a problem,” Norman said.

MAGA Republicans and Biden impeachment

Republicans aligned with former President Donald Trump are jumping to his defense against the torrent of criminal charges he faces, in part by including policies in must-pass bills that would restrict the powers of the FBI and the Justice Department, as well as cut federal funding for the three prosecutors who have secured grand jury indictments of him.

Those provisions are a non-starter with Democrats, but Trump has egged on the GOP-controlled House to pass them anyway.

They want to launch an impeachment inquiry into Biden, channeling Trump’s desire for revenge after he was impeached twice. Trump has pressured Republicans to quickly impeach Biden, and allies like Reps. Matt Gaetz of Florida and Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia have sought to push the cause forward.

McCarthy has been moving in the direction of an impeachment inquiry, calling it a “natural step forward” for the House GOP to gather more facts. But he recently made it clear he won’t open such an inquiry unilaterally — a majority of the House would first have to vote on it. With only four votes to spare in his Republican majority, it’s not clear McCarthy has the votes.

Gaetz has recently hinted at replacing McCarthy. When Rep. Eric Swalwell, D-Calif., taunted him on X, formerly Twitter, for making empty threats and predicted he’d never pull the trigger on a move to vacate the speaker’s chair, Gaetz seemed to accept the challenge.

“Bookmark this tweet,” he wrote.

McCarthy likes to remind Washington that he has defied his critics before — by winning the speaker’s gavel and by securing a debt limit agreement. He’ll have to do it again.

McCarthy told reporters Monday he’s “not at all” worried about losing his gavel. Asked about Gaetz, he said, “Matt is Matt.” McCarthy added that the House is “not spending the type of money the Senate wants to spend — not going to happen.”

A Republican divide over Ukraine

The GOP is bitterly divided over the future of aid to Ukraine.

One faction, led by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., favors the existing international order and believes thwarting Russia’s territorial expansion is important to that goal.

“The United States isn’t arming Ukraine out of a sense of charity. We are backing a fellow democracy because it is in our direct interest to do so,” McConnell said Monday on the Senate floor. “Republicans should be pressing President Biden to show more of it instead of dreaming about American retreat.”

But a right-wing populist faction in the party wants to turn off the spigot. It has the support of Trump, who has largely avoided the budget wars but weighed in to criticize Ukraine aid.

Roy told reporters: “Why are we talking about a Ukraine supplemental when we can’t even figure out how to fund our own operation of government? I want to know how every dollar of that $113 billion was spent. Come present that to me as a member of Congress, then talk to me about what you’re doing in Ukraine.”

Politically endangered Republicans

They aren’t the loudest faction in the House GOP, but these members from competitive districts are essential to preserving the majority. They don’t want a government shutdown, knowing that Republicans typically take the blame.

“We usually get blamed for it, one way or the other,” Senate Minority Whip John Thune, R-S.D. said. “I think most people just want to see us try and figure out a way to keep the trains running.”

Many are reluctant to open an impeachment inquiry, citing a lack of evidence Biden took bribes or acted corruptly to enrich himself or his son Hunter. All eyes will be on the 18 Republican lawmakers who represent districts that Biden won in 2020.

It’s harder for them to back impeachment when even Buck, a Freedom Caucus member, is skeptical; he said: “There is not a strong connection at this point between the evidence on Hunter Biden and any evidence connecting the president.”

Swing-district Republicans tend to be conflict-averse when it comes to intraparty spats, and they aren’t known for voting against McCarthy’s priorities. They’re seen as team players. But unlike many of the messaging bills they vote on, a shutdown and an impeachment vote would reach kitchen tables at home — and be difficult for them to defend politically.

Roy, who represents a safely Republican district, downplayed the dangers of partisan moves to holding House majority in 2024.

“Our job is to do our job now,” he said. “Politics take care of themselves.”

[ad_2]

Source link