[ad_1]

In 1990, two leaders from the Indigenous Penan community in Sarawak travelled the world seeking international support to stop unscrupulous logging in the Malaysian state’s biodiverse tropical rainforests.

33 years later and after several activists have either lost their lives to the cause or gone missing following the relentless pursuit of authorities, the very same leaders say that their communities are worse off.

“Logging activities have increased. Our living conditions have gotten worse and we have become poorer,” said Unga Paren, headman of the Penan village, Long Bagan in Sarawak. “Our big hope back then was for the international community to ask the government of Sarawak to reject the logging licences.”

“We waited, but nothing has happened,” he said.

Paren was one of the two Penan representatives who left Sarawak for the first time for the “Penan World Tour” in 1990. Then, he had met world leaders, including the United Nations Secretary General, across 13 different countries in six weeks to bring the plight of his community to global attention.

The Penan are a nomadic tribe that live in the tropical rainforests of Sarawak, and have historically depended on the forest for their food, health and livelihoods. However, industrial timber logging dating back to the 1980s threatened their way of life, and Penan communities have had to erect blockades against encroaching loggers and seek global support where the local government had failed them.

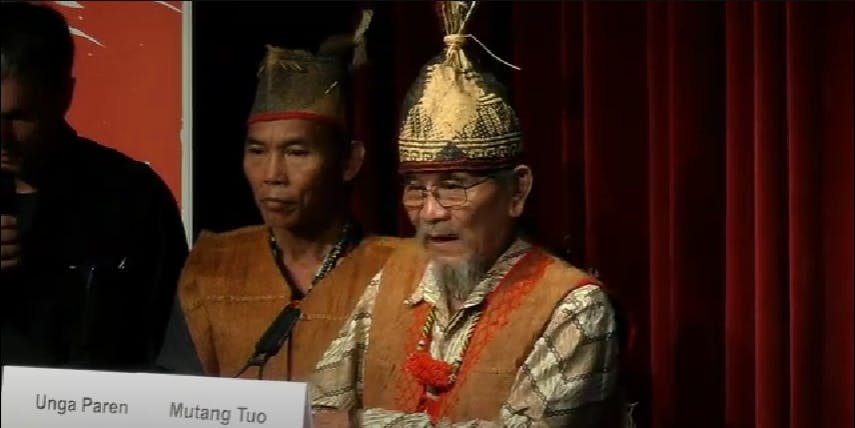

Penan village headmen Mutang Tuo (left) and Unga Paren (right) stood together on a world stage again for the first time since 1990 to plead for international support in their fight against deforestation. Image: Rainforest Tribunal/ YouTube

At the Rainforest Tribunal in Basel, Switzerland this week, Paren and his fellow Penan village headman Mutang Tuo stood together again on a world stage for the first time in three decades. This time, they again plead for international help in their ongoing struggle against industrial deforestation on their homeland.

“We still have a lot of problems in my village. The women and children are suffering,” said Tuo, who is headman of Long Payau village, at the tribunal, designed as political theatre where trials and witness hearings are held in the presence of a chair and a high-profile jury, although the events reviewed are real.

Villagers in Long Payau struggle to find decent-paying jobs and are unable to adapt to city life, said Tuo, who adds that the Penan are penalised for their strong stance on forest protection. When the locals return home, they shockingly find their rivers muddied and the forests gone, he said.

What is the Rainforest Tribunal?

Held in Basel, Switzerland on 15 August 2023, the Rainforest Tribunal mixes elements of a court of law with the theatrics of the stage to hear the grievances of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak, Malaysia who have suffered the consequences of decades of deforestation. It is organised by the Swiss-based NGO Bruno Manser-Fonds (BMF) which is currently embroiled in a lawsuit for alleged defamation and infringement of personality rights filed by Canadian property company Sakto Corporation and its two directors – Jamilah Mamud, daughter of Sarawak governor and former chief minister Abdul Taib Mahmud, and her husband Sean Murray. The claims were made based on BMF and its executive Lukas Straumann’s publications linking the plaintiffs to corrupt proceeds from Sarawak’s timber industry.

In the trial, 17 witnesses were called to the stand. They include international scientific experts, Malaysian officials, as well as Indigenous Sarawakians who flew half the globe to participate in the political theatre.

Symbolically, the tribunal was held a day before Swiss civil courts heard a lawsuit involving its organiser. Bruno Manser-Fonds, a Swiss-based non-governmental organisation (NGO), had been at the forefront of scrutinising the wealth of Sarawak governor Abdul Taib Mahmud, and is now being sued by the governor’s daughter and her husband, as well as a property company they run, for alleged defamation. Taib, who also ran Sarawak for 33 years as chief minister – the longest anyone has been in charge of the resource-rich state – has a reputation marred by corruption allegations and deforestation.

The actual lawsuit has been denounced by Malaysian and international civil society organisations. Unlike the Rainforest Tribunal, the case will not hear any Indigenous Sarawakians as witnesses. The suit has also been classified as a Strategic Lawsuit against Public Participation (SLAPP) by the European Coalition Against SLAPPs (CASE), which labelled it “legal harassment against an NGO advocating for Indigenous Peoples’ rights in Malaysia.” The case took five years to reach the courtroom and has cost BMF several hundred thousand Swiss Francs so far, CASE said.

This is not the first time a SLAPP has been levelled against organisations fighting for Indigenous rights in Sarawak. For example, Sarawakian timber company Samling Plywood has sued local NGO SAVE Rivers for defamation over remarks made in 2020 and 2021, which questioned Samling’s logging operations in Sarawak and their timber certification process. The case was delayed from being heard for the fourth time in May this year by Sarawak courts, after 160 organisations publicly called for the case to be withdrawn.

“

A Penan put it like this: an oil palm plantation is devoid of life. All the spirits are gone; it is death.

Ida Teilade, biologist and professor, University of Copenhagen

Deforestation in the Mulu area of Sarawak, Malaysia. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds

‘World’s worst example’ of tropical deforestation

The deforestation of Sarawak dates back to the 1980s, less than 10 years after the state welcomed the United Kingdom’s largest scientific expedition to Mulu, Sarawak in 1977. The quest, which lasted until 1978, led to the discovery of hundreds of new tropical species, including about 190 new species of rattan, said Robin Hanburry-Tenison, the lead explorer in the group.

“When we were there in 1977 and 1978, 95 per cent of the lowland dipterocarp rainforest was intact. Only about 5 per cent remains now,” Hanburry-Tenison told the Rainforest Tribunal. He added that scientists on the expedition largely agreed that the Indigenous Peoples who guided them were the “true experts of the forests.”

“There is no question that the destruction of Sarawak’s rainforests is the worst example of deforestation I’ve seen anywhere in the world,” he said, echoing a statement by former UK prime minister Gordon Brown, who in 2011 called the state’s deforestation “the biggest environmental crime of our times.”

The lawsuit filed by Canadian property firm and their directors, the Taib-Murrays, have been identified as a Strategic Lawsuit against Public Participation (SLAPP), which are used to silence activists, journalists and other advocates. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds

Former WWF-International director, member of the Club of Rome and biologist Claude Martin, shared this sentiment and warned that the large-scale deforestation witnessed in Sarawak made it prone to desertification. It had also made Borneo one of the most vulnerable biodiversity hotspots globally, said Ida Teilade, biologist and University of Copenhagen professor.

Theilade, who has regularly travelled to Sarawak since 1986 and traversed the major rivers in the state as recently as last month, said that previously logged forests, which could have been rehabilitated, have since been converted to oil palm plantations. Agribusiness, she said, has overtaken logging as the main threat to biodiversity in Sarawak.

“Biodiversity-wise, oil palm plantations are like deserts,” she said. “A Penan put it like this: an oil palm plantation is devoid of life. All the spirits are gone; it is death.”

Theilade, who is also chairperson for human rights non-profit International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, described the industrial-scale logging for timber in Sarawak as ‘ecocide’, a term now legally defined as unlawful or malicious acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and widespread, or long-term damage to the environment.

Global Forest Watch figures show that Sarawak has lost 3.18 million hectares of tree cover – a 27 per cent decrease – from 2001 to 2022.

Fearing death daily

Seeking justice for the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak has also been difficult and often dangerous for those who make it their lifelong cause.

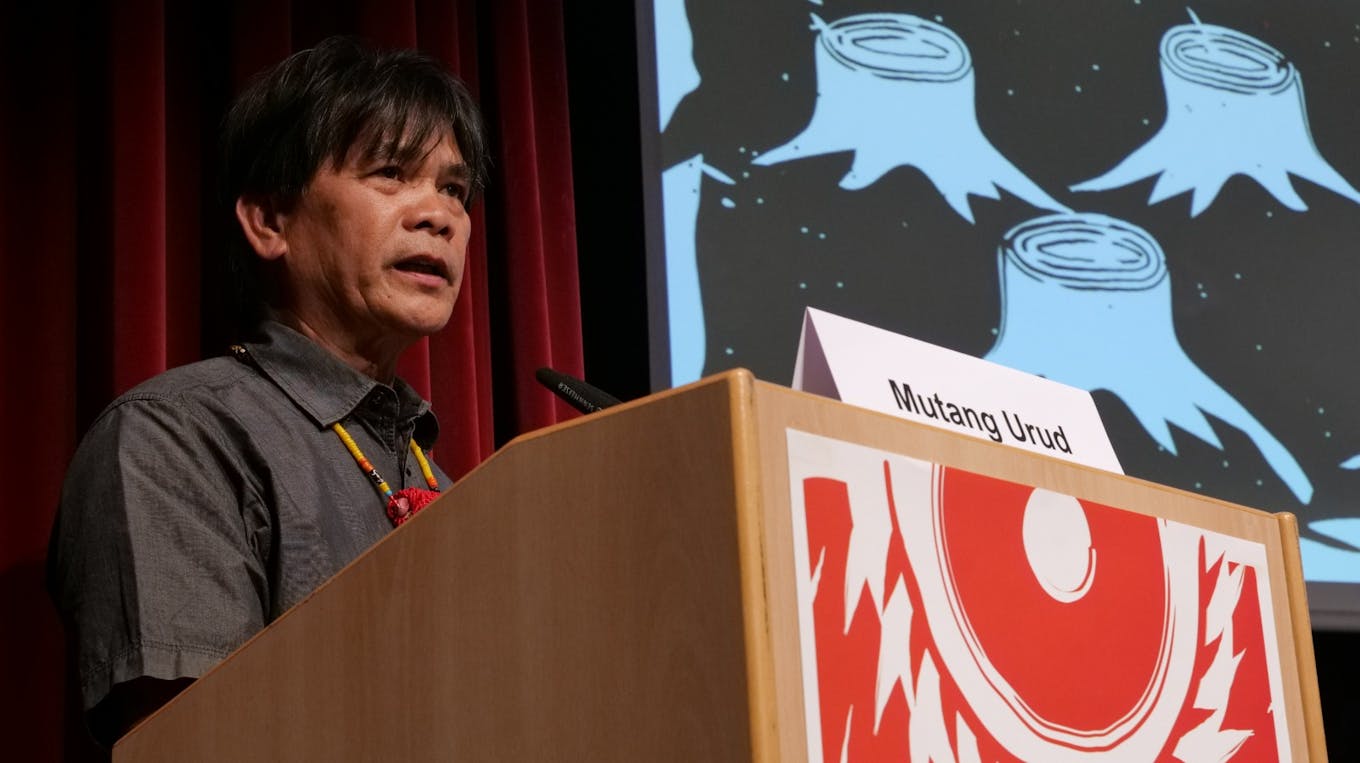

Mutang Urud, a human rights and environmental activist from the Kelabit tribe in Sarawak, described to the tribunal his 1992 arrest, interrogation and solitary confinement due to his role in organising and supporting blockades against loggers. He has since lived in exile in Canada, where he works with Aboriginal youth on environmental education.

“Clearly the strategy of the authorities is to harass and intimidate local communities,” he told the Rainforest Tribunal. “Nomadic groups who have never been in the city were put in jail as well.”

Mutang Urud, an activist from the Kelabit tribe in Sarawak, has lived in exile in Canada following his 1992 arrest for his role in organising and supporting indigenous blockades against loggers. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds/ Twitter

Blockades by Penan and other Indigenous communities to protect their ancestral labs have been hotbeds for these arrests. Hundreds were detained in an early Penan blockade in 1987, which included women and children who were later freed, said Komeok Joe, chief executive officer and founder of Penan non-profit Keruan.

News reports indicate that arrests of the Penan, including children, at blockades happened as recently as 2013 in Sarawak. This has not deterred the tribes, however, and many have persistently tried to obstruct the deforestation of their homeland. The latest is one in February this year, when the Penan erected a blockade at Ba Abang, near the town of Miri, to protest a timber company that was attempting to log on their land.

“We have lived in fear every day of losing our forests, our home. We have seen our land being eroded just like soil that is carried by the rain and ‘chased’ into the river,” Joe told the Rainforest Tribunal. “We have received verbal abuses and suffered undue harassment.”

The witnesses shared accounts of others who supported local communities in their land disputes losing their lives or facing the fate of persecution. The late Sarawakian political secretary Bill Kayong was shot and killed at a traffic intersection on his way to work in 2016, a year after both he and his employer, Sarawak assemblyman Michael Teo, started receiving threats of violence from a local oil palm company they were protesting against. Swiss environmentalist Bruno Manser, after whom BMF is named, disappeared in 2000 during a trip to Sarawak’s primeval forests.

“

The forest is what provides our livelihoods, and in return, it is our responsibility to protect the forest.

Mutang Tuo, village headman of Long Payau

More recently, Jerald Joseph, an activist lawyer who recently completed his term as the Commissioner of Malaysia’s Human Rights Commission (Suhakam), was barred from carrying out his work as Commissioner in Sarawak as he had been blacklisted from entering the state in the 1990s. He told the Rainforest Tribunal that this was due to his involvement in a 1996 campaign to inform rural villagers about the effects of the proposed Bakun dam.

Despite being part of the same country, Peninsular Malaysians are subject to immigration regulation when entering the East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, which include visa requirements and a rule that states that they should stay no more than 90 days in the same state per visit.

Joseph voiced support for Sarawak’s right to autonomous powers but said that abuse of power should not have happened in the first place. Blockades, he added, are acts of desperation, put up only when a government fails to do its duty to serve its citizens.

A 1992 Penan blockade in the village of Long Ajeng, Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds

‘Grand-scale transnational crime’

The Rainforest Tribunal saw fingers largely pointed at the Sarawak governor. During his tenure as chief minister, which lasted from 1981 to 2014, Taib had also served as minister for finance as well as the state’s resources and planning minister, giving him oversight of the approval of logging licences.

Speaking at the tribunal, Sarawak land rights lawyer and state assembly representative for Kuching See Chee How said that while timber export revenue for the state climbed as high as RM8 billion (US$1.70 billion) in 2008, only RM687 million (US$147.7 million) of that sum went to state coffers in the same year. Published research, he said, pointed to how much of the profits gained from the lucrative timber industry went to licensing for concessions, making these concessions a source of political patronage.

Members of the Rainforest Tribunal jury comprised Malaysian and international lawyers, activists and experts. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds/ Twitter

“The local struggles and victimisation of the Indigenous Peoples must be considered a grand-scale transnational crime,” said Malaysian lawyer and founder of the Centre to Combat Corruption & Cronyism Cynthia Gabriel, who chaired the jury of the Rainforest Tribunal.

BMF had invited Taib to take the stand at the tribunal, but attempts to contact his European representatives went unanswered, the jury heard. On Wednesday after the tribunal, a Kuching high court in Sarawak was informed that Taib was recuperating from surgery in Istanbul, Turkey.

A blockade against a mining company by Sarawak’s Penan community at the Ba Abang village in February 2023. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds

Willie Kagan, land rights activist of the Tering and Berawan people saw his childhood home in the UNESCO World Heritage Site and national park of Mulu turned into a luxury resort, of which Taib was an owner, according to company filings. When asked what he wanted from the state now that his land is gone, Kagan told the tribunal that he sought “retribution”.

“Part of our land has been destroyed, and the homes, plants and fruits are gone. We need them to pay us back. We want good water, electricity supply, infrastructure and internet access,” he said.

The Penans have additional demands, which are tied to protection of the rainforests: they want their rights to their ancestral lands to be recognised. “We need clean water, we need to have animals in the forest for us to hunt. This is exactly what we need – we need a healthy forest,” said Mutang Tuo.

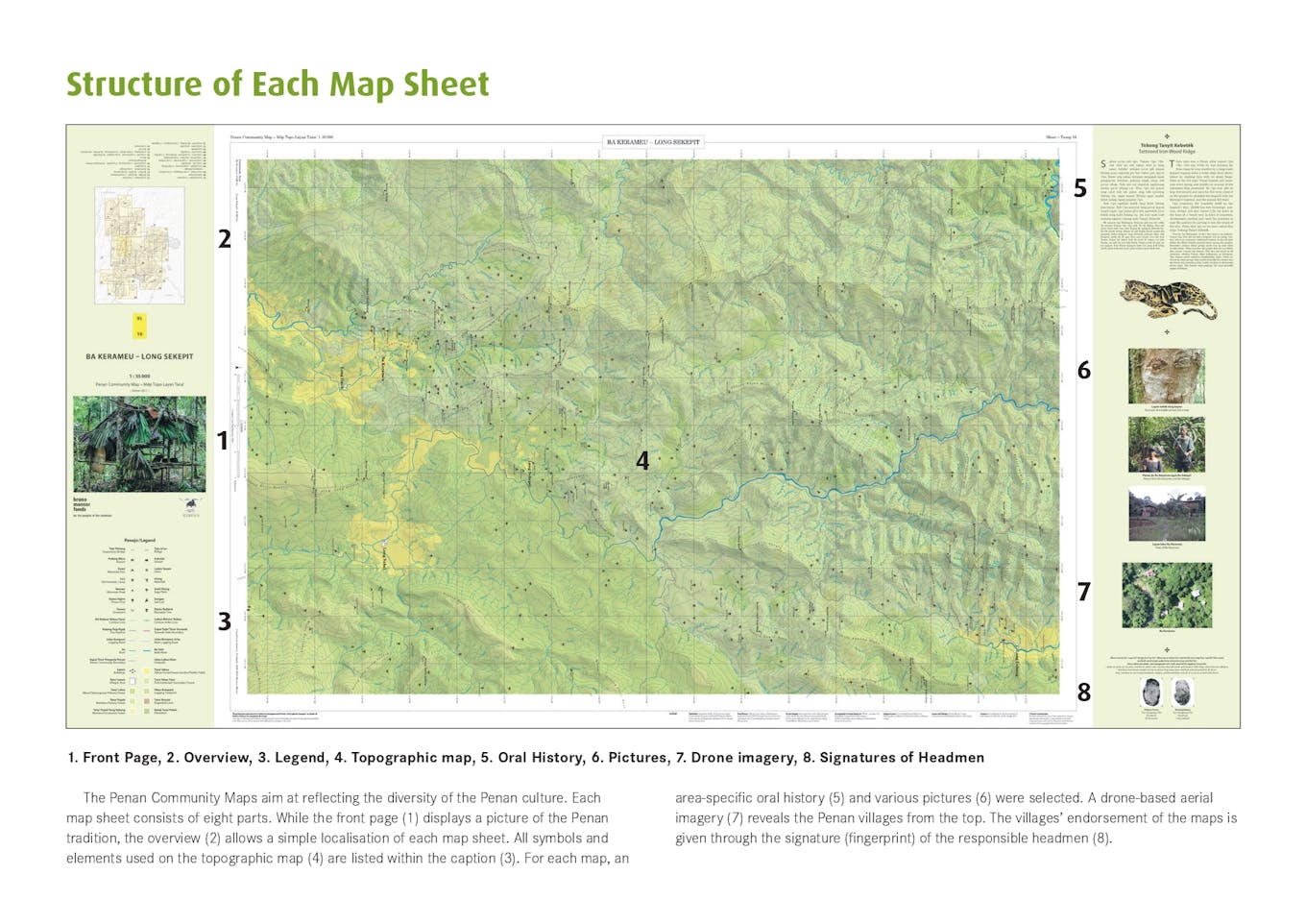

Their people have not been idle over the last 40 years. Beyond blockades, Sarawak’s Penan communities have also put together maps of their territories, collected data to support complaints against logging and plantation companies, and fought to have the remainder of Sarawak’s primary forests declared as peace parks.

“The forest is what provides our livelihoods and in return, it is our responsibility to protect the forest,” said Tuo.

The eastern Penan of Sarawak, a nomadic indigenous tribe, worked with Swiss non-governmental organisation to produce a total of 23 community map sheets across 63 Eastern Penan communities. Image: Bruno Manser-Fonds

The full proceedings of the Rainforest Tribunal can be accessed here:

Did you like this story? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Malaysia newsletter here for more ESG news and insights.

[ad_2]

Source link