[ad_1]

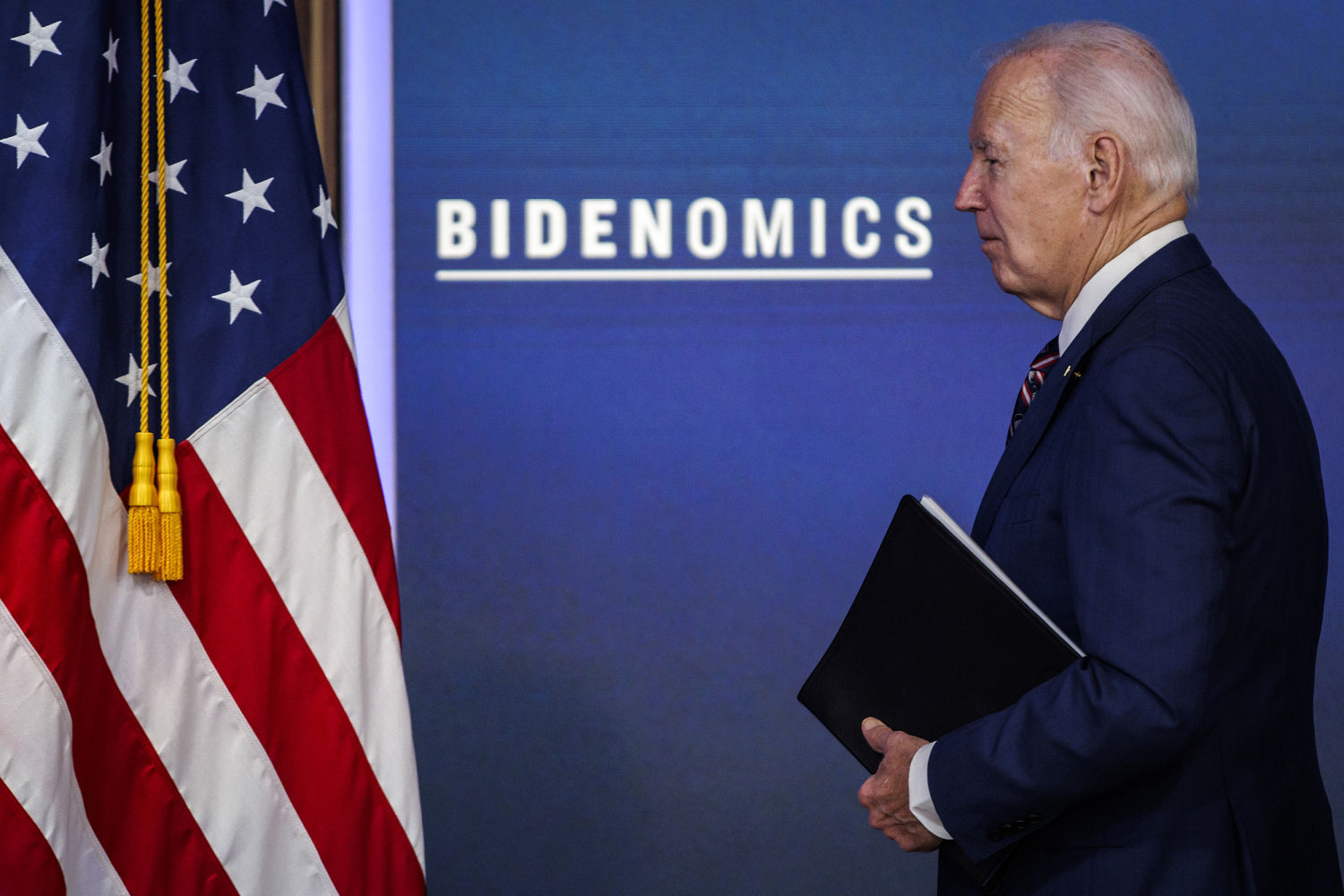

WASHINGTON — No one seems to like “Bidenomics,” the eponymous shorthand for Joe Biden’s economic policies — not voters, not Democratic officials, not even, at times, the president himself.

It’s a term that mystifies Americans and confounds even its namesake. “I don’t know what the hell that is,” Biden said in a speech in Philadelphia earlier this year.

In a September focus group with Pennsylvania swing voters, one participant told the research firm Engagious that the concept was a “jumbled mess,” adding that “it’s really hard to explain.”

Biden is undeterred — at least for now. He has made the state of the nation’s economy a central rationale of his re-election pitch, touting “Bidenomics” at events across the country. He talks about rapid job growth and billions of dollars in spending for roads, bridges and renewable energy projects on his watch.

Appearing in Minnesota last week, Biden described Bidenomics as “the American Dream” — twice in the same speech.

The trouble is, people aren’t buying it. Just as the phrase hasn’t caught on despite a low jobless rate, the underlying policies that Bidenomics purports to describe have left voters cold, polling shows. A Gallup survey in September showed that 48% of adults rated economic conditions as “poor,” the highest share in a year.

A University of Michigan monthly survey of attitudes toward the economy found that 20% of consumers expressed that their personal finances had deteriorated between Biden’s inauguration and September of this year.

More meaningful to Americans than the overall economic growth that Biden celebrates may be the stubborn reality that average food prices in U.S. cities have risen 20% since Biden took office. Or that the average price for a gallon of gas is $3.44 — less than it was a year ago but still about one-third higher than the pre-pandemic level.

Inflation has been cooling, down from a 40-year-high of 9% last year to less than 4%, but memories of high prices remain all too fresh, economists say.

“We’ve had quite significant inflation reduction while maintaining a tight labor market,” Jared Bernstein, chairman of Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, said in an interview. “And that’s been extremely welcome. At the same time, people want to hear about falling prices, because they remember what prices were, and they want their old prices back.”

Tethering the Biden name to a cluster of economic policies that may take years to fully kick in was a gamble from the start, Democratic strategists say. It personalizes economic conditions that are not necessarily under a president’s control.

“Whoever came up with the slogan Bidenomics should be fired,” said one Democratic strategist, who requested anonymity to speak more freely. “It’s probably the worst messaging you could ever imagine.”

It was actually the news media that first coined the term early in Biden’s presidency. When Biden and his advisers discussed whether to embrace it, the president was initially reluctant, two people familiar with internal White House discussions said. He worried that “Bidenomics” could backfire against him if the economy were to sour, one of the people said.

“I can understand that,” Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., said when asked about Biden’s unease with the term. “I don’t like it either.”

“The people that he [Biden] stands for don’t deal with economics,” added Clyburn, whose endorsement of Biden before the 2020 Democratic primary in South Carolina revived his candidacy and propelled him to the party nomination. “They deal with day-to-day issues. They have to educate their children and feed their families and develop their communities — and that doesn’t sound like ‘Bidenomics.’”

Maybe the only ones lapping up the term are Biden’s opponents. Republican candidates seem unified in the conviction that “Bidenomics” is a winning argument — for them. Rep. Dean Phillips, the Minnesota Democrat who launched a primary challenge to Biden last month, has placed Bidenomics in his crosshairs.

Speaking to reporters recently on his campaign bus in New Hampshire, Phillips said that “people are suffering and they don’t give a hoot about monikers and names and taglines. … I would just ask the American people, how are they doing? And the truth is, they’re really struggling.”

As often as Biden trots out the term, he has yet to give it a succinct definition. Bidenomics may be the American dream, but it’s also “about making things in rural America again,” he told the audience in Minnesota.

In speeches throughout the year, he has depicted Bidenomics as the antidote to low wages, the catalyst for manufacturing jobs, and the path to profitability for small businesses.

Heather Boushey, a member of Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, posted a 16-message thread on X, formerly known as Twitter, last month, explaining Bidenomics with the help of charts, graphs and color-coded maps.

“We’ll keep tracking these data but the story so far is remarkable: Bidenomics is building a better, fairer economy that responds to our challenges with bold action and grows the economy from the middle out and the bottom up,” she concluded.

Biden’s television advertising has thus far avoided the term Bidenomics, but has focused heavily on component pieces aimed at improving peoples’ day-to-day lives. The ads discuss lowering prescription drug costs, making renewable energy affordable, and passing new laws that boost American manufacturing jobs.

Ad campaigns take time to sink in, but Biden’s sluggish approval ratings suggest this one has a way to go. Biden’s likely challenger in the 2024 general election, former President Donald Trump, is running about even in head-to-head polling despite his myriad legal troubles.

“Originally, I would have said we didn’t repeat it enough,” Democratic pollster Celinda Lake said of Bidenomics. “I would have said we weren’t visible enough out there. I would have said we didn’t put enough advertising. But we’ve done all of that, and it still doesn’t break through.”

Biden campaign aides see signs that its ads are working. One spot featuring a Black farmer grateful for Biden’s spending in rural communities ranked in the top 80th percentile of ads tested when it came to voters’ choice of candidates, said a senior campaign aide who spoke on condition of anonymity to talk freely.

With the election a full year away, the campaign’s ad program isn’t focused on moving poll numbers, the aide added. At this point, the campaign is testing various messages to see which ones are effective, positioning itself for the general election race to come, the aide said. Themes that don’t stick with voters can always be discarded in favor of ones that do.

Still, some Democrats wouldn’t mind seeing Biden’s poll numbers climb. “Yes, I’m concerned about that, sure,” Clyburn said.

Does the campaign have a strategy to address that? “Well, I hope,” he added.

Inside Democratic circles, there’s a nagging concern that the party may be fighting old wars. A refrain of Democratic politics is that elections hinge on the economy and other issues pale in comparison. “It’s the economy stupid,” James Carville famously said during Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential bid.

But that sort of thinking predated Trump, a candidate unlike any other Democrats have faced. Trump allies have been devising plans to expand presidential power by converting nonpartisan civil servants into at-will employees who owe their jobs directly to the president. He has questioned the value of bedrock U.S. alliances. He now faces two criminal cases centered on his efforts to overturn the 2020 election along with two more criminal cases involving other matters. Economic policy isn’t the terrain on which to battle Trump, some pro-Biden Democrats say.

“The circus and the show that Donald Trump puts on is not a match for talking economic policy,” said Michael LaRosa, a former press secretary to first lady Jill Biden. “In 2016, any time Hillary [Clinton] talked about the economy, control rooms panned to empty podiums at Trump rallies because it was better television.”

“‘Bidenomics’ is just not sexy for the media to cover or simple enough for voters to digest, especially if they don’t see it or feel it,” he added.

Others counseled patience. At this early point in the race, Biden can afford to spend time reminding voters of bills passed and steps taken to revive the economy after the pandemic, said Jim Messina, who managed Barack Obama’s re-election campaign in 2012. There will be ample time to focus on Trump should he become the GOP nominee.

“Hammering away at Trump every day is just not as helpful as trying to tell them all the things Biden did,” Messina said. “He [Biden] did all these historic things. People don’t know it yet, and they’ve got to take this year to drive that.”

[ad_2]

Source link