[ad_1]

For half a century, Japan’s car makers were at the forefront of the global auto industry. Big names such as Toyota and Honda relentlessly pioneered new technology and flooded the market with successful new models. But the transition to electric has proved a stumbling block, and they’re now attempting to catch up with their rivals in the United States and China.

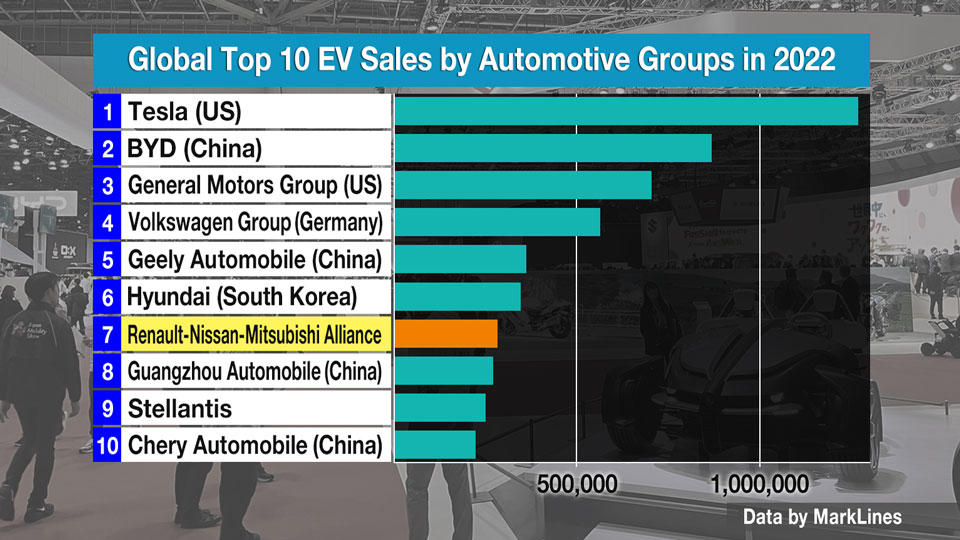

Analysis of electric vehicle sales across 62 markets in 2022 shows America’s Tesla led the way, shifting more than 1.2 million units. China’s BYD was next, with 860,000.

Only two Japanese automakers made the top 10 — Nissan Motor and Mitsubishi Motors — and even then, they achieved their number-7 ranking as part of a three-way alliance with France’s Renault.

The dismal showing was a source of angst for Japan’s top car brands, not least because a decade ago they were frontrunners in battery-powered cars. In 2010, Nissan became the first automaker in the world to roll out EVs on a mass scale, paving the way for what was sure to be another era of global dominance. The years that followed told a different story.

Slow to change

Fukao Sanshiro, Senior Fellow at Itochu Research Institute, blames “the innovator’s dilemma,” a phenomenon where the very decision-making that contributes to the success of a market-leading company also makes it slow to respond to disruptive technology.

Instead of embracing total innovation, he explains, Japan’s car-markers took a more conservative and gradual approach.

“In terms of eco-friendly cars, Japanese firms pursued hybrids equipped with internal combustion engines,” he says. “Engines … have been a major advantage for Japanese and other traditional automakers. But battery-powered EVs don’t use engines.”

Another problem, Fukao says, is supply. EV batteries are made up of scarce critical minerals, and Japanese firms, slow to get established in the market, are now finding it hard to get their hands on the resources they need.

Adding yet another dimension to the challenge is the transformational nature of the EV business, which may ultimately be driven less by hardware than software.

Fukao uses smartphones to illustrate. “The mobile phone sector has been transformed from an assembly business into a data business. The added value used to come from collecting and assembling parts. But with smartphones, the added value now comes from apps.

“It’s the same with EVs. How they use and provide data is becoming critically important.”

Fighting back

Japan’s car industry may be bruised, but it’s far from beaten.

One area where local automakers are confident they can make inroads is energy optimization. Honda recently partnered with Mitsubishi Corporation to explore ways of refining battery technology to deliver savings for drivers.

Engineers at Honda have already developed a system of swappable batteries that allows drivers to quickly and easily switch out a drained unit for a fully charged replacement.

Iwata Kazuyuki, who is overseeing the project, says the batteries can’t provide enough energy to power a regular-sized car, but they’re useful in smaller vehicles, such as motorbikes or micro delivery vans.

Not only do the batteries provide an instant charge, he says, they’re also smaller than conventional EV batteries, which helps to lower the overall cost of the vehicle.

Other manufacturers have been quick to spot the potential. Heavy equipment maker Komatsu worked with Honda to introduce the tech in a line of shovel-loaders. And it’s also been embraced by the makers of India’s iconic three-wheeled rickshaw taxis.

“If you want to make EVs that have the same driving range as combustion engine cars, then you end up with batteries that are bigger and heavier, and also more expensive,” Iwata says.

“If you only drive 20 kilometers a day, but you own a car that has a range of 600 kilometers, you’re just carrying weight you don’t need. With this system, vehicles only have to carry the weight they do need. That will definitely improve efficiency.”

The scaled-down approach has other potential benefits, says Fukao from the Itochu Research Institute, who thinks Japanese companies have a lot to gain by focusing on tech that’s nimble and efficient.

To make his case, he points to the best-selling EV in Japan, Nissan’s Sakura. The diminutive, affordably priced car only has a range of 180 kilometers per charge, but that’s more than enough for most drivers, particularly in regional areas where all their needs are a short drive away.

“Renewable energy can be produced and consumed locally,” Fukao adds. “So I think producing small electric vehicles that meet the needs of residents in regional areas can be a big opportunity.”

The idea that small is beautiful has prevailed in Japan for centuries. It’s a mindset that may ultimately be required to propel the country’s big automakers back to the front of the global pack.

[ad_2]

Source link