[ad_1]

There is no such thing as a certainty in business or economics.

But there are trends, and since 2014 the trend in the value of Irish exports has been upwards.

As the Irish economy recovered from the financial crisis in the early part of the last decade, so too did exports.

Since falling to €89bn in 2013 the value of total exports has been rising steadily, more than doubling since then to reach a record €208.59bn last year.

Remember, that is despite the Covid-19 pandemic, which wreaked havoc on the global economy.

But this year, something has changed.

Why, what is different?

At the back end of last year, exports were still powering ahead, driven in the main by a roaring pharma trade that makes up 30-40% of our total external trade of goods.

And that trend continued into the first couple of months of 2023.

But by March the first signs started to appear that something might be up, with the overall value of exports falling compared to the same month last year.

In particular, exports of medical and pharmaceutical products were down €2bn versus March 2022.

By April, the monthly fall in medical and pharma exports had widened to €5bn, leading to the first decline in the State’s headline export trade in nearly a decade.

But it was not just pharma that was showing problems. Exports in the valuable and previously reliable electrical machinery and equipment segment also dropped by a third or €1.5bn.

Things did bounce back again in June, with the second highest monthly export total ever recorded. And oddly pharma was once again the big driver.

July also saw another year-on-year increase.

But the latest figures, released last week, showed a further 17% decline in overall exports in August compared to the same month in 2022.

Organic chemicals, often used in pharma manufacturing, fell €5bn, although bucking the trend, exports of medical and pharma products, which made up 43% of total exports, actually rose by 6%.

Overall though, that sector’s exports remain down 6% over the first eight months of the year, at €51.6bn.

While the value of exported electrical machinery, apparatus and appliances and parts, which includes high value goods like semiconductors, was down 51% in the month and has fallen almost 41% so far this year, to €5.8bn.

So what is going on in the pharma sector?

Ireland has a massive biopharma manufacturing sector that produces raw materials and finished products for the global market.

According to IDA Ireland, over 85 pharma companies operate here, and BiopharmaChem Ireland, which represents the sector, claims it employs 26,000 people directly and another 25,000 indirectly.

Their output makes Ireland the third largest exporter of biopharma goods in the world.

Within that cohort though there are some particularly large players, like Pfizer and MSD for example.

Pfizer, as everyone knows, was centrally involved in bringing the pandemic under control through the development and manufacture of its vaccine with BioNTech.

The company’s Grangecastle site in Dublin was one of a small number around the world that produced the active ingredient for the drug, which was then exported to be made into finished vaccine elsewhere.

It also has an anti-viral drug, Paxlovid and the active ingredient for it was produced in Pfizer’s manufacturing plant in Ringaskiddy, before being finished at another plant in Newbridge, Co Kildare.

Analysts are cautious about drawing a direct causal line between the drop in exports from Ireland and the fall off in production of Pfizer’s Covid vaccine and its anti-viral.

But there certainly seems to be a correlation and in its latest Quarterly Economic Bulletin, the Central Bank pointed to the reduction in glycoside and vaccination exports, of which vaccines make up the most part.

“The exceptional increase in overall exports of chemicals and related products in 2022 was linked to the increase in Covid-19 vaccine production,” it said.

“In addition, it is likely to have reflected in part a degree of stockpiling of pharmaceutical products in light of uncertainty over the path of the pandemic as well as concerns over global supply chain disruptions last year.

“As the pandemic has eased and global supply chain conditions improved, a run down of accumulated stocks and a return to more normal production levels are likely to explain a significant part of the decline in pharma exports in the first half of 2023 compared to 2022.”

Matt Moran, Director of BioPharmaChem Ireland, agrees with the analysis but says the dip is likely to have been caused by decisions across more than just one company, particularly around stock.

“Some companies may well have … increased their stocks as a kind of a defence, because supply chains became pretty erratic during the pandemic as well,” he said.

“So I’d say they were starting to err on the conservative side … in terms of ensuring supplies were out there.”

And what then about electrical machinery – what’s the issue there?

In a word, semiconductors.

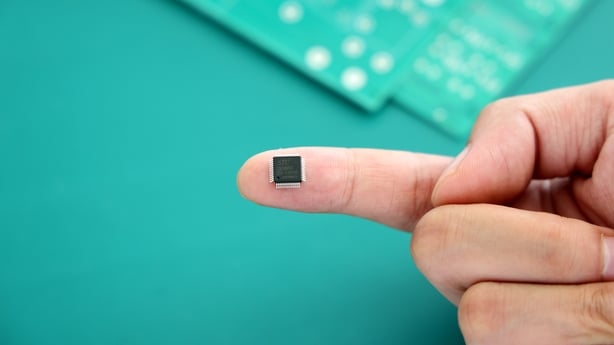

The electrical machinery category includes microchips, made by a small number of manufacturers in this country, including Intel.

These are high value products, used in everything from smartphones, to cars, to toasters.

In its analysis, the Central Bank said the precise cause of the reduction in semiconductor exports so far this year is unclear.

But it said it may reflect a number of developments adversely affecting this part of the global ICT manufacturing sector.

The drop in exports of these chips from Ireland is mainly the result of a reduction in exports to China, which takes 70% of all semiconductors made in Ireland.

But exports of chips to the US have also fallen too.

The Central Bank speculates that it is possible the decline in Irish exports in this sector is a result of headwinds for the global economy coming from reduced Chinese trade, changes in demand for certain tech products and government policy changes internationally.

“In relation to the latter, in October 2022, the Biden Administration announced new restrictions on exports to China of advanced integrated circuits (ICs), computers and components containing advanced ICs, semiconductor manufacturing equipment and related software and technology,” the Central Bank wrote.

“The restrictions cover exports from US-based firms but they also apply to any company worldwide that uses US semiconductor technology in its production processes.

“It is not possible to determine from publicly available information whether the export controls have affected exports of semiconductors from Ireland.

“However, since US-owned multinational enterprises account for a significant share of exports from this sector in Ireland, it is possible that the restrictions are playing a role in the weakness in Ireland China ICT goods exports to date in 2023.”

So should we be concerned?

It seems strange that fluctuations in just two segments of the Irish export economy can have such an outsized effect.

But that’s really just a reflection of the level of reliance we have built up on pharma and the IT sector.

The impact is felt wider than just the two sectors though.

Economic growth as measured by GDP contracted by 2.8% in the first three months of the year, with industrial production falling 13%, as a result primarily of the pharma sector volatility.

That recovered in the second quarter, with GDP growth of 3.3% between April and June.

But over the summer we also saw signs of unexpected weakness in corporation tax receipts, which may, or may not, be linked to the troubles faced by these two sectors.

Matt Moran from BioPharmaChem Ireland is upbeat though about the pharma industry’s future here.

He points to recent investment announcements from MSD, which has invested €1bn in its Dunboyne and Carlow sites, as well as Astellas, which is building a new €330 million operation in Tralee.

“Pfizer are putting €1bn into their Grangecastle facility at the moment as well,” he said.

“So it is a very strong statement of intent and there’s no concern being expressed by any of the companies themselves about Ireland as a future place.

“There’s a lot of them that are still reinvesting at the moment. So that normally results in increased output. So I’d say the medium term is still strong for the sector.”

That said, Pfizer is mulling how it is going to implement $3.5bn in cuts around the world, as a result of the drop off in Covid therapies demand.

Whether or not that will result in job losses among the company’s 5,000 Ireland based staff remains to be seen.

As for semi-conductor demand, the future is less clear.

Intel has just recently opened “Fab 34” at its Leixlip campus after a €17bn investment that doubles its manufacturing space here.

But increased production capacity is only useful if there is demand and the extent of that into the future remains uncertain.

“It is possible that future quarters could see a rebound in exports from both sectors, in particular since large-scale physical investments have taken place over recent years to expand production facilities in both the pharmaceutical and ICT manufacturing sectors,” the Central Bank said.

“Nevertheless, the decline in trade in the first half of 2023 is a reminder of the wider risks to the Irish economy from the concentration of exports in a small number of highly globalised, multinational-dominated sectors.

“This characteristic of the economy leaves it exposed in the event of a downturn in global demand, industry or firm-specific structural changes or an acceleration of geo-economic fragmentation.”

A warning not to be ignored.

[ad_2]

Source link