[ad_1]

JOHOR BARU, Dec 2 — Malaysian hawker, Sim, was a step away from buying fresh prawns during a holiday in the Pontian district of Johor, only to be stopped by the exorbitant price quoted by the seller.

The 63-year-old Johorean, who declined to give his full name, claimed that the prices were immediately jacked up after the Singaporean tourists who came before him blurted out: “Wah, so cheap!”

“I wanted to buy prawns, and I heard the seller quoted the Singaporean group RM20. But once it was my turn, the seller quoted me RM30,” he told TODAY.

Although this happened some years ago, the story remains fresh in his mind. While Sim said he had no problem welcoming Singaporeans to travel around his home state, he had only one request from them.

Advertisement

“It’s better to keep quiet when buying things. There’s no need to say so loudly that the prices are cheap. What about the locals who don’t think the prices are affordable?” he said.

Sim’s experience will resonate with many Johor residents even today, particularly those residing in the state capital, as Johor Baru has been a favourite destination of Singaporeans for the longest time.

The perennial “bird people” behaviour — characterised by the continuous exclamations of “cheap, cheap, cheap” — found its way into the limelight recently when a Singaporean financial content creator publicly urged Singaporeans to be more humble and sensitive to Malaysians.

Advertisement

It’s not just the word “cheap” that runs the risk of being deemed insensitive, but also the general behaviour that some Singaporeans exhibit in their excitement to shop for good bargains in Johor Baru due to the weaker Malaysian ringgit.

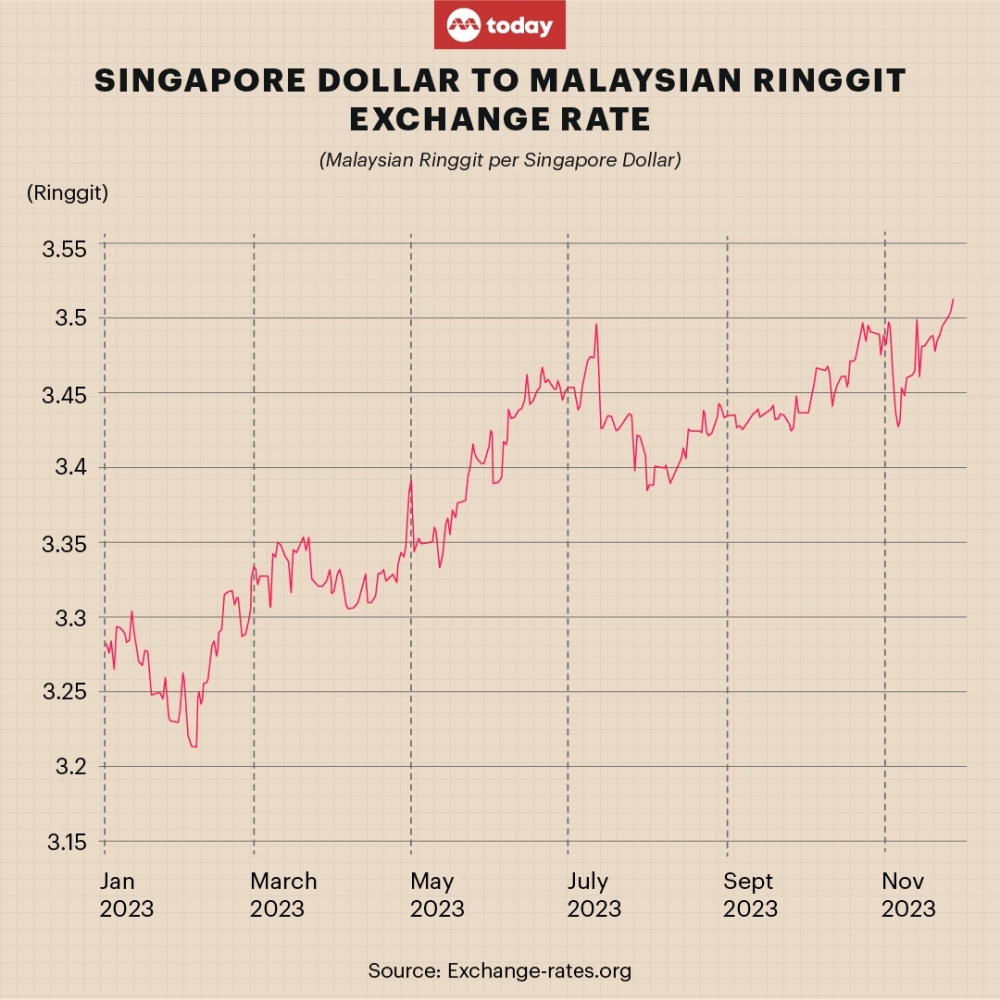

True enough, during TODAY’s visit to Johor Baru last weekend (Nov 26 and 27), this reporter heard a woman, presumably from the Lion City, proclaiming loudly: “Wow, the prices here. How much are they divided by 3.5? In Singapore dollar.”

The shop visited by the said woman was just opposite the chwee kueh (steamed rice cakes) stall operated by Sim along Jalan Tan Hiok Nee, 1km away from the Customs, Immigration and Quarantine (CIQ) Complex.

“There’s good and bad when Singaporeans come over. They have higher spending power, which is good. But they should just be quiet about it,” said Sim.

Johor Baru residents TODAY spoke to appeared disapproving of Singaporeans treating the city as a bargain haven, as there is a perception that the cost of living has soared in the past year due to more tourist arrivals from Singapore and their ability to spend.

However, contrary to their views, Johor business owners and economists said that Singaporean spending is not the main reason why Johoreans are grappling with rising costs.

They cited other global and domestic factors, such as the country’s economic woes and policies Malaysia adopted during the pandemic as well as current geopolitical tensions, for the inflation faced by Johoreans.

Singaporeans have been flocking to Johor for shopping and holiday following the easing of Covid-19 restrictions and the reopening of borders, with lengthy traffic jams at the checkpoints a common occurrence during the weekends and public holidays.

For example, during the long weekend from Aug 31 to Sept 4, a record number of more than 1.7 million travellers passed through Woodlands and Tuas checkpoints.

One factor is the steady strengthening of the Singapore dollar against the ringgit, from about 3 at the start of 2020 to new highs of 3.17 in April 2022 and 3.5 today.

What Johor residents say

Sales executive Siti Atiqah Ahmad Daud, 35, nodded in agreement when asked if the influx of Singaporean tourists into Johor Baru had created disamenities for Johoreans like herself.

“A lot of Singaporeans come here because of their stronger currency. They want to eat good food and buy things for cheap here.

“But for locals like us, it’s not very good. It’s like there’s ‘competition’ because they can afford to buy many things at higher prices, and we can’t,” she told TODAY.

The mother of three children aged two to 15 said the prices of staple food, such as rice and meat, have risen sharply since the movement control order (MCO) — imposed in early 2020 as Covid-19 cases soared everywhere — was officially lifted at the end of 2021.

“Now, a lot of things cost at least 50 per cent more than they used to. It’s very sad to see the strength of our ringgit going down,” she lamented.

Similarly, retail shop manager Beanz Ho, 31, believes that the higher cost of living in Johor Baru can be attributed to more tourists, especially those from Singapore, coming into the city to spend.

“Almost everything is getting more expensive, such as groceries, cooking ingredients, chicken, and meat. If I owned a business in JB, it would be good because there would be more sales.

“But if I were a resident earning a salary, it would be tougher because the salary might not be enough for the higher cost of living. It’s not balanced,” he said, adding that the impending increase in the Sales and Service Tax (SST) from six to eight per cent in Malaysia next year worries him.

For this reason, Ho prefers to stay in Kulai, a town some 30km from Johor Baru.

“Although I have to drive back and forth every day, I don’t mind because petrol costs around RM300 (S$85) a month. But if I were to get a house in JB, the price range is about RM800,000 to RM1 million, which isn’t affordable at all,” he said.

Restaurant manager Chong Guo Hui, 31, said a fresh graduate earning RM2,000 a month will not be able to spend much because a typical meal at a food court, inclusive of food and beverage, would amount to RM15.

“It is possible that businesses are willing to jack up their prices because more Singaporeans travel here, and they have better purchasing power than the locals.

“But on the other hand, I think Johoreans going over to Singapore to work contributes to the rising prices here too because when they bring (Singapore dollars) back, they are more willing to spend as their salary is three times higher,” he said.

Chong, who also has family members working in Singapore, urged the state government to devise an effective plan for retaining talents because the “brain drain” situation that Johor is facing, in his opinion, is the most pressing issue.

“It’s getting harder to hire locals. We must think about retaining Malaysians because it’s not sustainable for businesses to keep hiring foreigners,” he said.

To be sure, some residents believe that the rising cost of living is not just due to the Singapore factor but is also caused by a confluence of reasons, such as the weakening ringgit due to political shifts in the country, and geopolitical tensions.

Sales executive Siti Atiqah Ahmad Daud believes that the influx of Singaporean tourists into Johor Baru had created disamenities for Johoreans like herself. — TODAY pic

A financial consultant, who wished to be known only as Hiew YZ, told TODAY that he believes that the political changes in the last three years have a significant part to play in the depreciating ringgit.

Before Anwar Ibrahim became prime minister following the 2022 general election, Malaysia had had three prime ministers in as many years.

“Our Prime Minister (Anwar) has just held the position for a year. There’s still a lot of time until the next election, so hopefully, things will be better by then,” Hiew said.

Retiree Chin AB, 76, said Malaysians should not “blame” Singaporeans for soaring prices because inflation is happening worldwide, not just in the country.

“Perhaps, yes, there will be some impact, but ultimately, Singaporeans coming over makes JB a livelier place,” he said.

What do business owners think?

TODAY’s interviews with several entrepreneurs found that while they had mixed views on Singapore’s impact on inflation in Johor, some did not think that the influx of Singaporeans is a significant reason behind rising prices.

Contrary to residents’ beliefs, some of these businesses were more concerned about domestic and external factors, such as the weakening ringgit, which has led to a spike in the cost of raw materials.

Triple K Cafe shop owner Keoh Teik Hoe, who serves beef noodles, said he gets his beef supply from Australia and New Zealand, and the suppliers trade in United States dollars.

Amid the continuing weakening of the ringgit this year, he told TODAY that beef prices had increased by 20 per cent this year. In October, the ringgit fell to a 25-year low against the US dollar.

Singaporeans make up 30 per cent of Keoh’s customer base, while the rest are primarily locals and regular patrons.

“I cannot simply increase my prices. For now, I will still absorb the cost because I can still get by even with profits going down by 30 per cent.”

Keoh was adamant in his belief that “it is not right” for business owners to adjust their prices “just because” Singaporeans can afford the higher prices.

“Then what about the locals? Yes, Singaporeans have higher spending power, but they are only here on weekends. The locals here can visit your business several times a week because they live here,” he said.

Third-generation owner of Hiap Joo Bakery, Lim Toh Huei, 35, said the prices of bananas had shot up after the MCO, so the bakery had to change its banana bread prices from RM10 to RM12 last year.

“You can get 1kg of bananas for RM2.50 previously, but now it costs RM4.50 to RM5. The prices fluctuate, but since the last review, we don’t plan to change our pricing again for now. We can still bear the costs first,” he said.

Lim, whose business is largely patronised by Singaporeans on weekends, said Johor Baru is “definitely impacted” by Singaporeans pouring into the city.

“For businesses like mine, it’s good. But for the rest of us, it means we need to continue working hard to put food on the table.

“Now that times are tougher, I think it’s important for everyone, especially young adults, to come out and work to earn their keep because there’s no such thing as a free lunch in this world,” he said.

Third-generation owner of Hiap Joo Bakery, Lim Toh Huei, whose business is largely patronised by Singaporeans on weekends, said Johor Baru is “definitely impacted” by Singaporeans pouring into the city. — TODAY pic

Multi-label fashion store Bev C owner Beverly Ang, 40, said while she agreed that Singaporeans have higher spending power, she did not see this as the reason for price hikes in Malaysia, particularly Johor Baru.

“I think it’s because our political situation is not stable. Our Prime Minister has only served for a year, so the situation directly impacts our currency exchange rate.”

Owner of Coffee Bar 1438, who wished to be identified only as Firdaus, shared the same sentiment as Ang.

He said Johor Baru is a tourist hub that attracts tourists from other countries, such as South Korea and China. Hence, from a business perspective, the growing tourism sector in the city bodes well for him.

“Singaporeans have been coming to JB for a long time, so I don’t think their arrivals affect prices here a lot. The two main reasons are our weak currency and political changes,” he said.

Sixty per cent of Ang’s customers are Singaporeans, while Firdaus serves around 85 per cent of Singaporean customers.

How have prices changed in Johor?

According to a report by the Department of Statistics in Malaysia, Johor’s year-on-year inflation as of October — the latest figures available — is at 1.7 per cent.

The state ranks sixth highest, right behind Penang (1.8 per cent), Selangor (1.9 per cent), Perak (2.2 per cent), Sarawak (2.5 per cent) and the Federal Territory of Putrajaya (2.7 per cent).

The top five categories that reported the highest year-on-year inflation in Johor are:

- education (7.5 per cent)

- restaurants and hotels (4.1 per cent)

- health (3.8 per cent)

- food and beverages (3 per cent)

- furnishing and household maintenance (2.4 per cent)

With the report also listing the average prices of goods across various states, TODAY looked at the December 2022 edition for some insights into how prices had changed in the past year in Johor.

Not all goods saw a drastic spike, but some notable ones included berangan bananas, which used to cost RM5.42 per kg in December 2022. It was RM6.40 in October, an increase of 18 per cent in 10 months.

Tomatoes of the same weight, which cost RM5.59 in December 2022, were priced at RM6.46 in October, up almost 16 per cent.

Consumers paid an average price of RM6.90 for a plate of chicken rice last year. Ten months later, they had to fork out RM7.38, or 7 per cent more.

A 10kg bag of rice sets consumers back by RM30.15 in October, compared to RM26.15 last year, or 15 per cent lower.

The bag of rice would have cost even more if not for Malaysia’s subsidy scheme on petrol, cooking oil and essential food items, such as rice.

What’s behind higher prices in Johor

To get a clearer picture of the factors behind cost-of-living concerns in Johor Baru, TODAY spoke to economists to understand the big picture and whether Singaporeans are the main contributors to higher prices for staple goods.

Sunway University economics professor Yeah Kim Leng said that Singaporeans, too, are facing rising costs of living in their country, which has prompted them to travel to Johor Baru for cheaper goods.

Singaporeans have been grappling with higher prices as the core inflation of the country rose from 3.0 in September to 3.3 per cent in October. In January and February, the figures stood at 5.5 per cent, a 14-year high.

“The rising cost of living in Singapore has driven many Singaporeans to shop for their daily essentials in Johor Baru,” said Prof Yeah.

“To cope with the excess demand, Johor Baru needs to effectively look into capacity expansion. If they cannot expand, and demand is greater than supply, this leads to excess demand, which will then cause upward price pressures and inflation.”

In economics terms, Prof Yeah described the phenomenon as “overheating”, which occurs when an economy is unable to expand to meet the increased demand, resulting in prolonged periods of inflation.

For now, he has yet to see Johor Baru reach this stage despite the higher price pressures faced due to some slack in the labour and housing markets.

“Businesses may boom and charge higher prices, but we also have to take into consideration that most of this demand is seasonal. You only see a big surge in demand on the weekends and public holidays.

“These are the challenges faced by businesses in Johor Baru. They will have to factor seasonality into their plans and ensure the business is still sustainable for the rest of the week when there’s no increase in consumer demand from Singapore.”

Prof Yeah said Johor Baru can see the influx of Singaporean consumers as an opportunity instead of a threat.

“Johor has both a combination of investor demand and traffic from Singapore. The question now is how the state can advance further to tap into opportunities presented to them in this scenario.”

Carmelo Ferlito, chief executive officer of Kuala Lumpur-based think tank Centre for Market Education, said Malaysia is now “paying the consequences” for the policies introduced to alleviate the financial burdens of households during the pandemic.

An example of one such policy, according to Ferlito, is the launch of economic stimulus packages, such as Prihatin, which was said to be among the largest in the world.

The RM250 billion Prihatin package can be described as the Malaysian equivalent of Singapore’s Unity and Resilience Budgets in 2020.

Ferlito told TODAY: “You cannot think …(you can) ‘switch off’ the economy to implement fiscal and monetary expansions, and not have inflation.” He mentioned this in reference to the MCO, which led to an economic standstill.

“So inflation was caused by the government, not by Singaporeans.”

Asked about the reason for Malaysia’s depreciating ringgit, Ferlito attributed it to two main factors — recent geopolitical tensions, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, and China’s economic slowdown.

On the first point, Ferlito noted that while it may seem as if the ringgit is weakening, in actuality, it is the US dollar strengthening because it is still considered the best reserve of value.

“In moments of uncertainty, the US dollar remains the refuge. The people tend to purchase more safe-haven currencies, so in turn, this has weakened the other currencies, and as a consequence, the ringgit suffers.

“This is paired with the high-interest rate policy adopted by the Federal Reserve, attracting foreign investors towards the greenback,” he said.

Domestically, Ferlito said Malaysia has been impacted by China’s economic slowdown. “China was particularly ‘suicidal’ in its policies on the lockdowns, and now it’s paying the cost. You cannot switch on and off the economy like it was a car or an engine.”

Since Malaysia is an important trade partner of China, he said: “The weakening of China directly affects Malaysia.”

Asked what the Malaysian government can do to help citizens, Ferlito said it is vital for Malaysia to adopt business — and market-friendly solutions for the economy to gain strength on its own.

“Giving cash handouts might seem like a politically appealing manoeuvre, but this actually makes people poorer because, in the end, everything will become more expensive.”

On its part, the Johor state government has announced various schemes to help residents cope with inflation.

These include a RM300 monthly allowance given to Johor fishermen and a rice aid programme where all households are entitled to a 10kg bag of rice. Married couples get relief with a one-off RM1,000 financial assistance under a programme for newlyweds.

In announcing a RM1.8 billion budget for 2024 on Nov 23, Johor chief minister Onn Hafiz Ghazi said: ”We understand that the rakyat (Malay for people) is facing hardships such as the high cost of living, with necessities becoming more expensive and the drop in ringgit value, which have contributed to the rising cost of living.

“The 2024 state budget was planned as a continuation of our effort to develop Johor’s economy for the wellbeing of the Bangsa Johor people,” he added.

The state has set aside more than RM300 million in the Johor 2024 Budget to assist residents who fall within the lowest 40 per cent category by income.

A tale of two cities’ symbiotic ties

While the jury is still out on the extent to which Singaporeans have contributed to rising prices in Johor Baru, the symbiotic relationship between the two cities linked by the Causeway cannot be denied.

That relationship became most pronounced when the pandemic forced both places to close off their borders to visitors.

Shopping malls and the surrounding tourist enclaves in Johor Baru were empty, with nary a soul in sight save for retail staff.

“It’s clear that the shops there exist to cater to the needs of Singaporeans,” said Hazree Mohd Turee, managing director of BGA Malaysia. BGA, short for BowerGroupAsia, works with companies across various sectors to provide solutions and help them strategise and expand.

Now that demand has gone back up after Covid-19 restrictions were lifted, it is no surprise that people from Singapore are crossing the Causeway in droves, eager to buy groceries and household items at a lower cost again.

In 2022, Johor received over nine million tourists, and Hazree said around 80 per cent of the total came from Singapore. Before the pandemic, in 2019, the total stood at over 17 million, with more than 13 million coming from Singapore.

A Johorean himself, Hazree said Johor Baru residents are most impacted by the prices of wet goods, such as chicken and fruits.

“Chicken costs as high as RM17 per kg in Johor, which is almost S$5 to Singaporeans. But in Singapore, they have to pay S$8.65 per kg. It’s a vast difference.

“That’s why at places like wet markets, the sellers prefer to sell to Singaporeans because they can jack up the prices. Even after the price hikes, prices in Johor are still at least 50 per cent cheaper to them (Singaporeans).

“This was the trend before the pandemic, and I’m sure it will continue now,” he said.

Where food is concerned, there is more to the story than meets the eye. Hazree explained that Malaysia is a net importer of food as the produce grown locally is not enough to meet domestic demand after catering to exports.

“As a net importer trading in (US dollars), prices will shoot up given our ringgit’s current situation,” he said, adding that it is imperative for Malaysia to tackle food security concerns so that the country can be more self-reliant.

Price issues aside, congestion is also another everyday phenomenon in Johor Baru.

And when the weekends and school holidays are here, the city sees more Singapore-registered cars cruising on Malaysian roads.

Siti Atiqah, the sales executive, said that traffic conditions could become quite bothersome with a mix of Johor and Singapore cars in the city.

“I think the government can consider controlling the number of Singapore cars coming into JB over the weekend. Don’t just allow everyone to come in because this worsens the congestion here.”

Kedai Dhoby Shanghai co-owner Hakim Abdullah, 23, was among several residents interviewed by TODAY who expressed hope for a reliable MRT system in the city one day to ease congestion.

“But personally, I don’t think congestion is a major issue. It makes me feel that the city is very happening,” he said. — TODAY

[ad_2]

Source link