[ad_1]

Introductory Remarks to the Fiscal Monitor Press Conference

By Vitor Gaspar, Director, IMF Fiscal Affairs Department

Marrakech, Morocco

October 11, 2023

As prepared for delivery

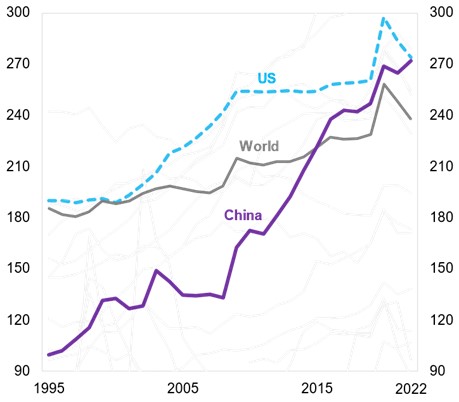

Global debt has risen persistently over the last 75 years. The mountain range got its tallest and steepest peak, in 2020, the year of the pandemic, at 258 percent of GDP. In the following two years, a strong rebound in economic activity, accompanied by an unexpected inflation surge, pushed debt lower by 20 percentage points of GDP. This brought debts about 2/3 of the way back to pre-pandemic levels. In 2022, total debt liabilities of governments, non-financial corporations and households stood at $235 trillion (238 percent of GDP). The chart “Mountains of Debt” covers the period from 1995.

Mountains of Debt

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) Global Debt Database (GDD) and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Data as a percent of GDP. Dimmed lines represent a sample of selected countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Korea, Turkey, United Kingdom and United States.

The United States and China clearly stand out. Together they represent almost half of world’s total debt outside the financial sector. Their shares are, respectively, 30 percent and 20 percent. China’s debt rose much more rapidly than global debt (and also much faster than Chinese GDP): from 1 percent of world debt, in 1995, to 20 percent, in 2022. As a percentage of Chinese GDP, the debt ratio trebled and converged to the United States’ level. Judging solely by its debt-to-GDP ratio (well above the average for Emerging Markets and Developing Economies), China would fit well into the group of advanced economies. Low Income Developing Countries have much lower levels of debt liabilities. Limited access to finance is testimony of the deep divide between rich and poor countries.

These are some of the highlights from the 2023 Update of the IMF’s Global Debt Database.

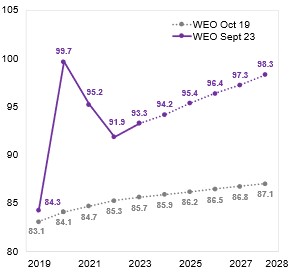

An important question is: will total debt resume its rising trend? That may or may not be the case. However, this much is certain: general government debt in the world is expected to increase. Why? It would be accurate to answer that the rising trend is due to the major global economies (the US and China stand out again). But it would be more relevant to state that the turning up of debt reflects slowing growth, rising real interest rates and budget deficits dipping further into red (in part reflecting rising borrowing costs). The bottom line is that Global Public Debt is now substantially higher, and it is projected to grow considerably faster than in pre-pandemic projections.

Although debt vulnerabilities and risks remain elevated and fiscal restraint a much needed ingredient in the policy mix in many corners, IMF’s assessment is that the risk of a “systemic” wave of sovereign debt defaults remains low.

Global Public Debt Turns Back Up

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook (WEO) and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Data shows Global General Government Debt as a percent of GDP.

For all countries it is becoming more challenging to balance the fiscal equation. First, debts are generally elevated and borrowing costs are rising. Given that effective interest rates on public debt lag market rates, the effect will likely be very persistent. Second, public expectations about the role of the budget have expanded over time, in part from the experience during COVID 19. Priority policy goals include the eradication of poverty and hunger, climate change, digitalization and artificial intelligence, competitiveness, and growth and much else. Third, there is a widespread aversion to taxation. So much so that it is not a great exaggeration to speak about political red lines on taxation.

Trilemmas

Source: Fiscal Monitor, October 2023.

But the way the government budget constraint binds varies widely across countries. In some cases, it is binding right now with the government having insufficient resources to pay urgent bills and no access to market financing. For example, in many low-income countries interest expenses and valuation effects on public debt represent a large and growing fraction of tax revenues. In other cases, while immediate financial pressures are absent, the perpetuation of current policies entails an unsustainable fiscal path, as for example, in the United States and China. In addition, there is another dimension to this issue. In most countries, tighter fiscal policies are needed, not only to reconstitute buffers and contain public finance risks, but also to contribute to central banks’ efforts in favor of a timely return to inflation targets.

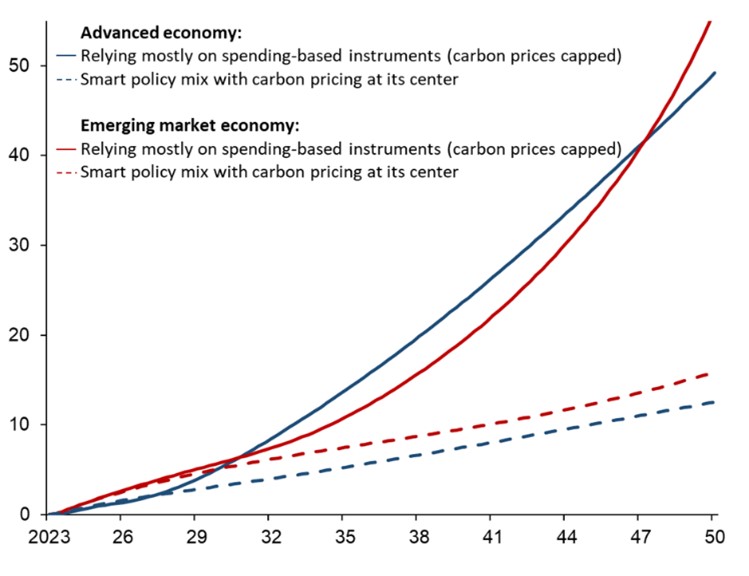

The Fiscal Monitor – Climate Cross-Roads looks at the fiscal implications from the green transition. The baseline is business as usual (BAU). Under such assumption it is possible to identify ambition gaps – the difference between countries’ own nationally defined contributions and what is required to deliver on the Paris agreement goals – and policy gaps – the difference between the national targets and the outcomes achievable under BAU. The baseline corresponds to the V-shaped chart shown at the beginning. But, in addition, it fails to deliver a successful energy transition to net zero with catastrophic consequences. The Fiscal Monitor shows that scaling-up the current policy mix – heavy on subsidies and other components of public spending – to deliver net zero leads to an accumulation of public debt by 40 to 50 percentage points of GDP for a representative advanced economy and for a representative emerging market economy.

Paths to Net Zero

Source: Fiscal Monitor, October 2023 and IMF staff simulations.

Note: Data shows debt dynamics as a percent of GDP.

The Fiscal Monitor argues that to circumvent this terrible trade-off it is necessary to rely on a combination of policy instruments. Carbon pricing (carbon taxation) is a necessary component of the policy mix, but it is not sufficient. It must be complemented by instruments aimed at correcting remaining market failures. One relevant example relates to the production, diffusion, and adoption of green technologies. Fiscal support is also necessary to facilitate the unavoidable costly adjustments undergone by vulnerable households, workers, communities and corporations. Climate Cross-Roads presents illustrative combinations of policies that limit the increase in the public debt ration to the range of 10 – 15 percentage points of GDP, by 2050. That is a pressure that looks manageable through the adjustment of other parts of the budget.

Countries with limited fiscal space, low tax capacity, and expensive or non-existing access to market financing face large adaptation costs. In many cases, these countries also have to deal with financial difficulties on their efforts to pursue sustainable, inclusive and resilient development. These countries should prioritize and target spending (for example, eliminating fuel subsidies). They should also intensify their efforts to improve tax capacity with special emphasis on institutional building and enlarging tax bases. That is discussed in the SDN “Building Tax Capacity in Developing Countries”.

The private sector has a crucial role to play in a successful green transition. Public policies should provide a framework that favors private sector participation in investment and financing. The Fiscal Monitor takes a closer look at the critical role of firms. The GFSR provides an overview of Climate Finance. In 2021 and 2022, the IMF has supported the efforts, in more than 150 member states, to upgrade tax capacity and to strengthen the market for Treasury liabilities.

Ahead of COP 28, it is important to reiterate that a global pragmatic side deal among large players – e.g. the US, China, India, the EU and the AU – could make a decisive contribution. The AU membership of the G20 is a very important step. By incorporating a carbon price floor, the global deal would help the most effective and efficient policy instrument to become a focal point for policy action in the World. By including financial and technological transfers and revenue sharing mechanisms, the global deal could ease the financial divide and contribute to the achievement of the sustainable development goals, including the eradication of poverty and hunger.

The IMF has an important role to play at the center of the international monetary system, to preserve sound public finances and financial stability. It is an essential piece of the Global Safety Net. Urgent support from members is necessary to increase quota resources and secure funding for the concessional Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust.

The logic of the three-way policy trade-off – or policy trilemma – outlined in the Fiscal Monitor applies beyond climate. In fact, it applies to any policy goal that implies additional budget spending. Faced with myriad spending pressures, political red lines limiting taxation at an insufficient level translate directly into larger deficits that push debt to ever rising heights.

Something must give to balance the fiscal equation. Policy ambitions may be scaled down or political red lines on taxation be moved if financial stability is to prevail. The Fiscal Monitor shows that a smart policy-mix maps the way out of the trilemma.

A global side agreement would further help.

[ad_2]

Source link