[ad_1]

Born on April 14, 1927, in Newark, N.J., Victor J. Kemper displayed a keen interest in electronics at an early age. Though he watched Saturday afternoon serials at the local movie theater now and then, he spent more time building radios and repairing his neighbors’ television sets. “I think I was an engineer from the day I was born,” he said. “Becoming a cinematographer — or, in fact, having anything to do with the film business — was the furthest thing from my mind.”

After graduating from Seton Hall University, Kemper found work at a local TV station, where he recorded and mixed sound, repaired cameras and served as technical director on studio productions. When he learned that a California company had invented 2” black-and-white videotape and was touting it as a replacement for film, he paid his own way to California to be trained in the new system. Upon returning to the East Coast, he discovered he was the only freelancer in the area with that expertise. The year was 1954.

The New York commercial house Elliot, Unger & Elliot hired Kemper to train its staff cinematographers to shoot video. “People were very nervous — everybody in New York thought videotape was going to replace film,” Kemper recalled. But Screen Gems soon bought EUE and closed its video department, prompting Kemper and a colleague to buy the equipment and open their own video-production company. After a couple of years, they lost their financing. “At that point, every cameraman I helped train in video called and offered to hire me, but I had to start as an assistant cameraman,” said Kemper. “People thought I was nuts [to do it], but that’s where I learned about the cameras — how to field-strip them, how to use and operate them.”

He quickly advanced to camera operator, working several times for Arthur Ornitz, ASC, and his break came in 1969, when he was hired to be the stand-by/second-unit cinematographer for Italian cinematographer Aldo Tonti on John Cassavetes’ Husbands. A couple of days into the shoot, Cassavetes decided the language barrier with Tonti was too great, and he handed the reins to Kemper. “We shot more than 1.5 million feet of film during 10 weeks in New York and 12 weeks in London,” Kemper later told American Cinematographer. “That’s the way Cassavetes worked.”

A year later, Kemper connected with special-effects cinematographer Joseph Westheimer, ASC, on the feature Who Is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying All Those Terrible Things About Me? Impressed by Kemper’s meticulous approach to the bluescreen photography, which Kemper had never done before, Westheimer proposed him for ASC membership. Kemper joined the Society on Oct. 4, 1971.

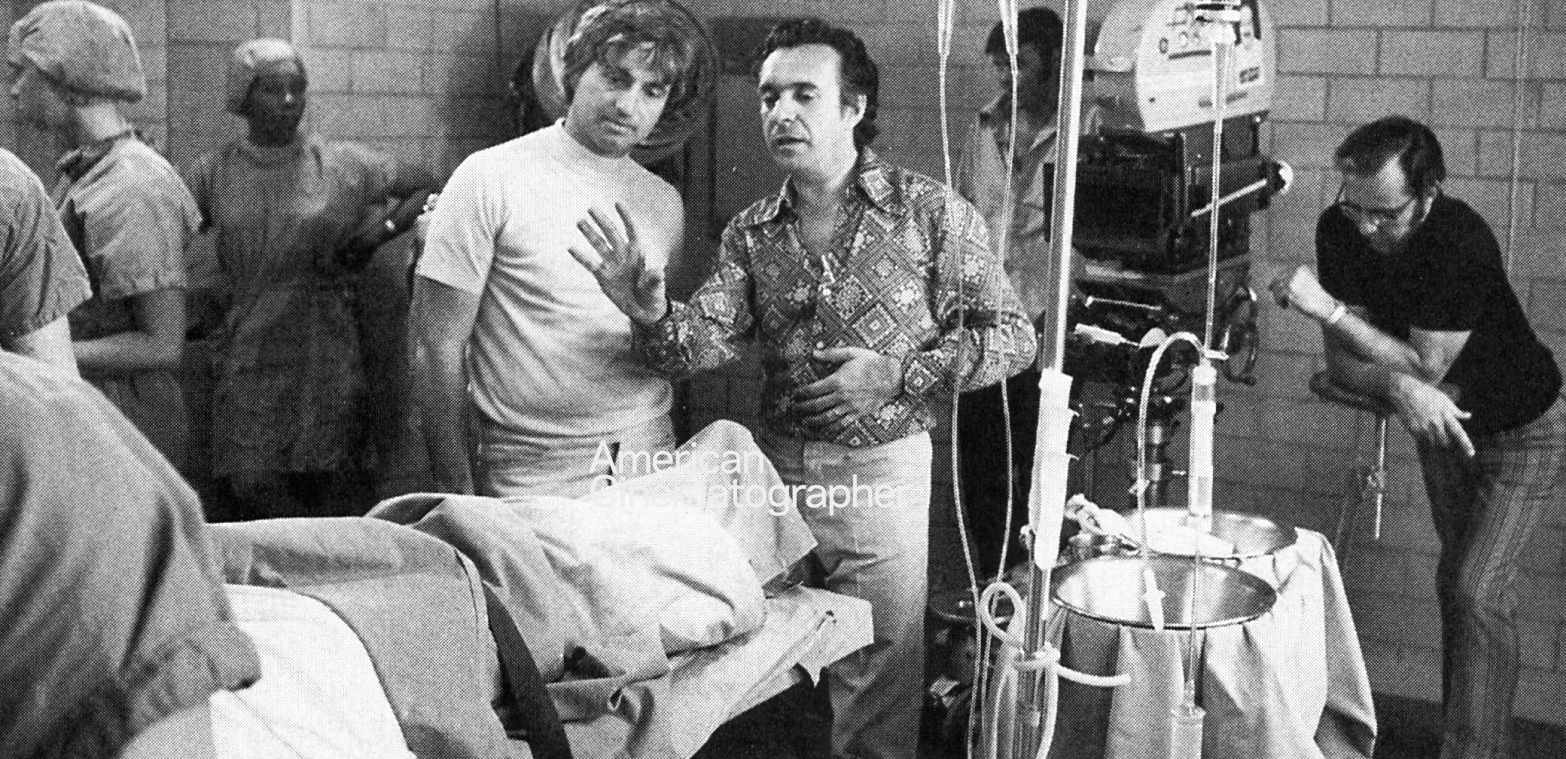

A diverse array of projects followed, including the black comedy The Hospital, the documentary-style political film The Candidate and the Neil Simon comedy Last of the Red Hot Lovers, which marked Kemper’s first experience working on a Hollywood soundstage. “It was a lot different than shooting in New York, [where] we worked with less because it was the only way we could work,” he noted.

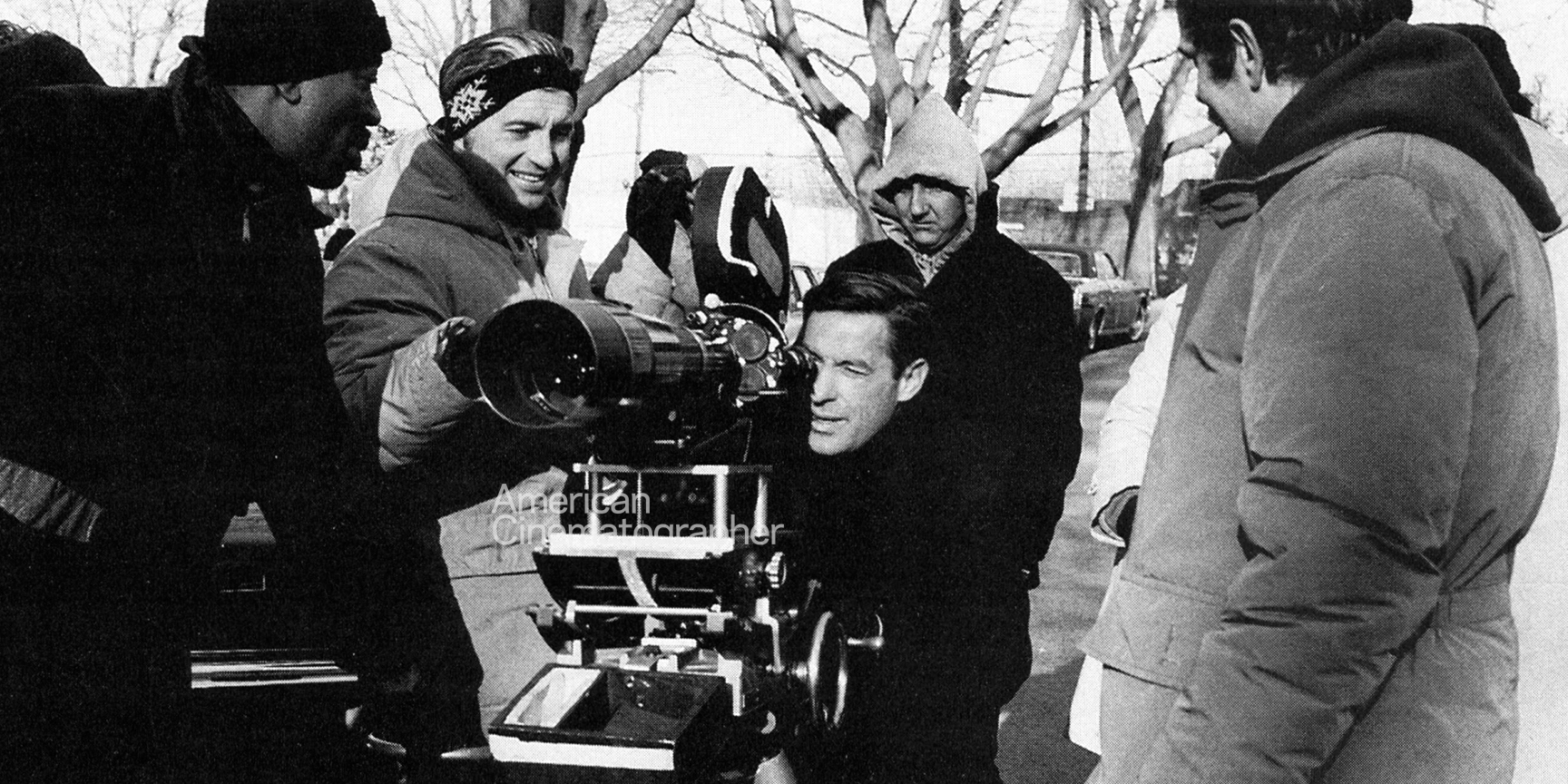

Michael Ritchie’s The Candidate, which was detailed in the Sept. ’72 issue of AC, gave a new twist to location shooting: Aiming for the feel of a TV-news piece, the filmmakers often captured the title character (played by Robert Redford) amid real crowds in public places and during live events, such as a high-school football team’s homecoming rally and the annual end-of-year festivities on Montgomery Street in San Francisco’s financial district. “This required us to ‘wing it,’ and by that I don’t mean we didn’t prepare carefully — we did,” said Kemper. “We knew there would be just one chance to get things on film; our first take had to be right because it usually couldn’t be repeated.” He ran two cameras throughout the shoot and used as many as four on some crowd scenes.

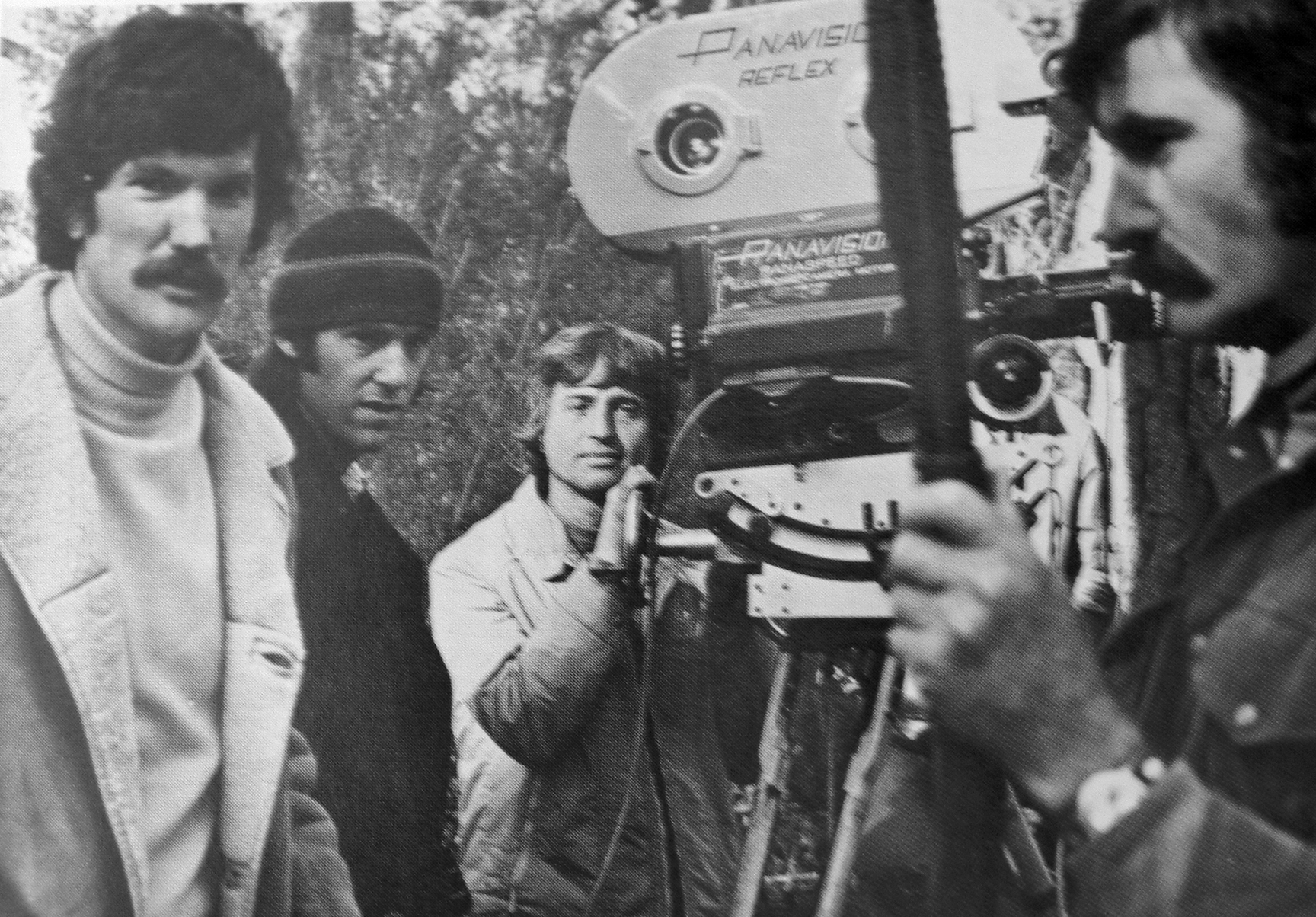

Director Sidney Lumet set a similar goal of visual immediacy on Dog Day Afternoon, which was inspired by a true story about an attempted bank robbery. “Sidney told me to make the film look as if it was happening right then in Brooklyn,” said Kemper. In determining how to best achieve this, “I just kept going over the script, and I watched the rehearsals.”

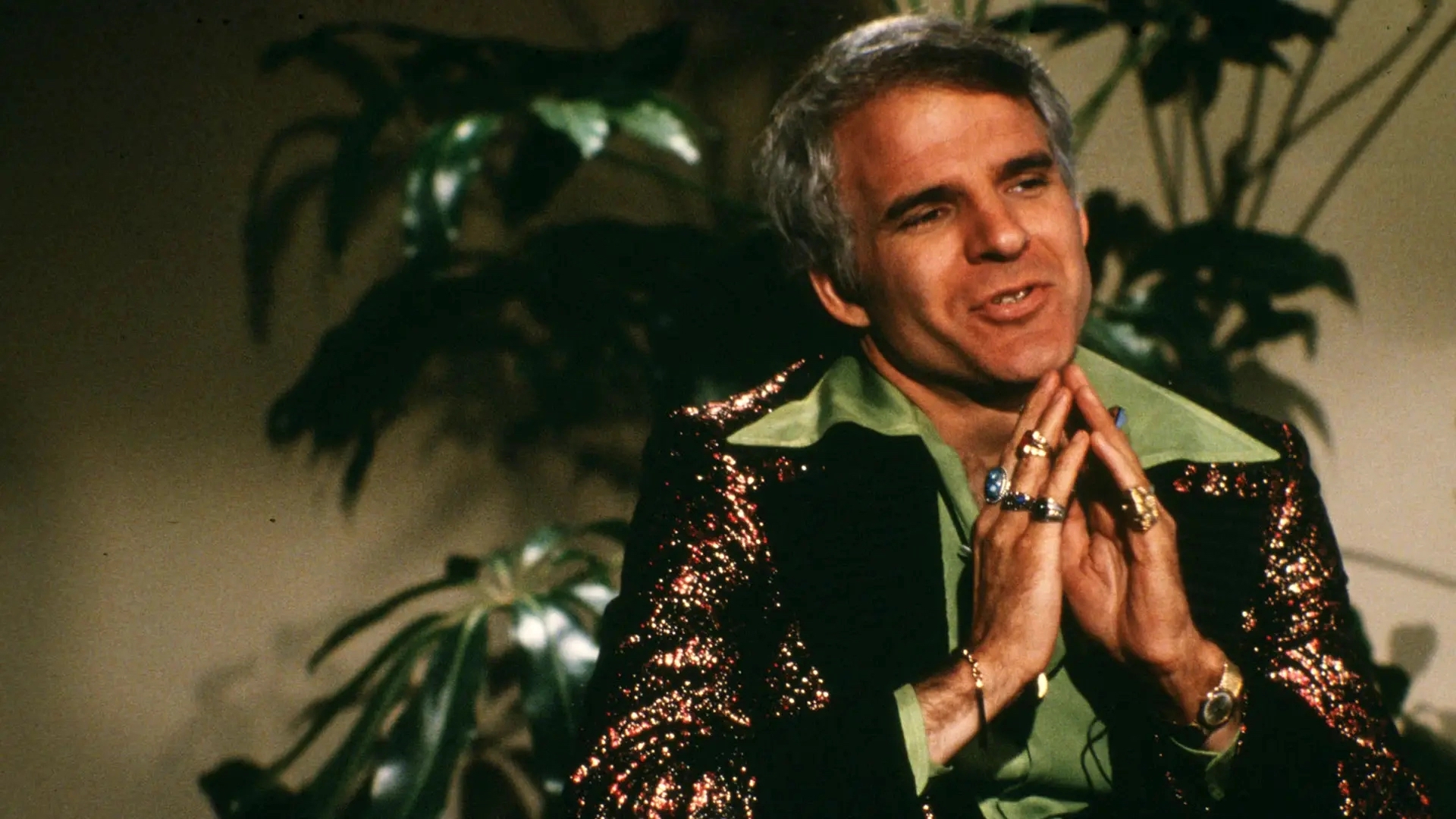

Kemper’s feature credits also included They Might Be Giants, The Last Tycoon, Mikey and Nicky, Slap Shot, … And Justice for All, The Jerk, The Four Seasons, National Lampoon’s Vacation, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure and Clue.

Kemper received Emmy and ASC award nominations for the telefilm Kojak: The Price of Justice, and his TV credits also included The Atlanta Child Murders, Too Rich: The Secret Life of Doris Duke and On Golden Pond.

Kemper was elected to multiple terms on the ASC Board of Governors, and he served as president of the organization from 1993-’97 and 1999-2002. During this time, he was instrumental in modernizing the Society by introducing computers and organizational software, creating a business structure for employees, overseeing an essential remodel on the Clubhouse, and launching the Society’s first website, in addition to many other initiatives.

He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997 (complete profile here) and later served as the Kodak Cinematographer in Residence at the University of California-Los Angeles in 2008.

He is survived by his wife of 72 years, Claire, three children — Jan Walsh, Steven Kemper and Florie Bunzel — and three grandchildren, Daniel Walsh, Maggie Bunzel and Jordan Bunzel.

[ad_2]

Source link