[ad_1]

When the elderly man approached after Bernard Wilkin had given a speech on battlefield bones, it’s safe to say that Wilkin was not expecting the man’s opening gambit.

“You should know that I have Prussians in my attic,” the man told him, recalled Wilkin, an author and researcher, in an interview Thursday with NBC News. “I was taken aback by that.”

Last week, forensic analysis revealed that the man was storing rare remains from the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s final defeat to coalition forces led by Britain’s Duke of Wellington and Gen. Gebhard von Blücher’s Prussian army after dominating much of Europe.

“Basically he had them for decades,” Wilkin said of the man, who has chosen to remain anonymous and did not want the bones to end up in the trash after he died.

Wilkin, a senior researcher at the State Archives of Belgium, said the man approached him in November at a conference in the town of Waterloo, around 20 miles south of Brussels, Belgium’s capital.

Wilkin said he had just finished talking about how common it was for farmers across Europe to dig up and sell bones to the sugar industry, focusing on how the bones were used to produce a particular kind of charcoal that would purify sugar.

Estimates vary on how many died at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, but the number runs into the thousands.

Many were buried in mass graves that were looted, plundered for bones for sugar production, Wilkin said.

Only two complete human skeletons have ever been formally excavated from the Waterloo battlefield, according to the British charity Waterloo Uncovered.

A few days after the conference, Wilkin visited the man’s home in the village of Plancenoit, where he showed him the bones.

Wilkin said the man was an avid Waterloo memorabilia collector, who had been in possession of the bones since the 1980s after they were given to him by a friend who had discovered them near a battlefield in Plancenoit. He added it was the site where French forces had fought the Prussians.

As the director of a small museum about the Battle of Waterloo, the man wrestled with the idea of exhibiting the bones, but for “ethical” reasons, stored them away in his attic instead, Wilkin said.

The man also told him about a friend who “owns four British soldiers,” Wilkin said, adding that the second man was a metal detector enthusiast who had illegally searched a second battlefield in Waterloo.

Analysis of those bones by a team of anthropologists and forensic doctors confirmed last week that they were the remains of at least six British soldiers, not four as was initially assumed.

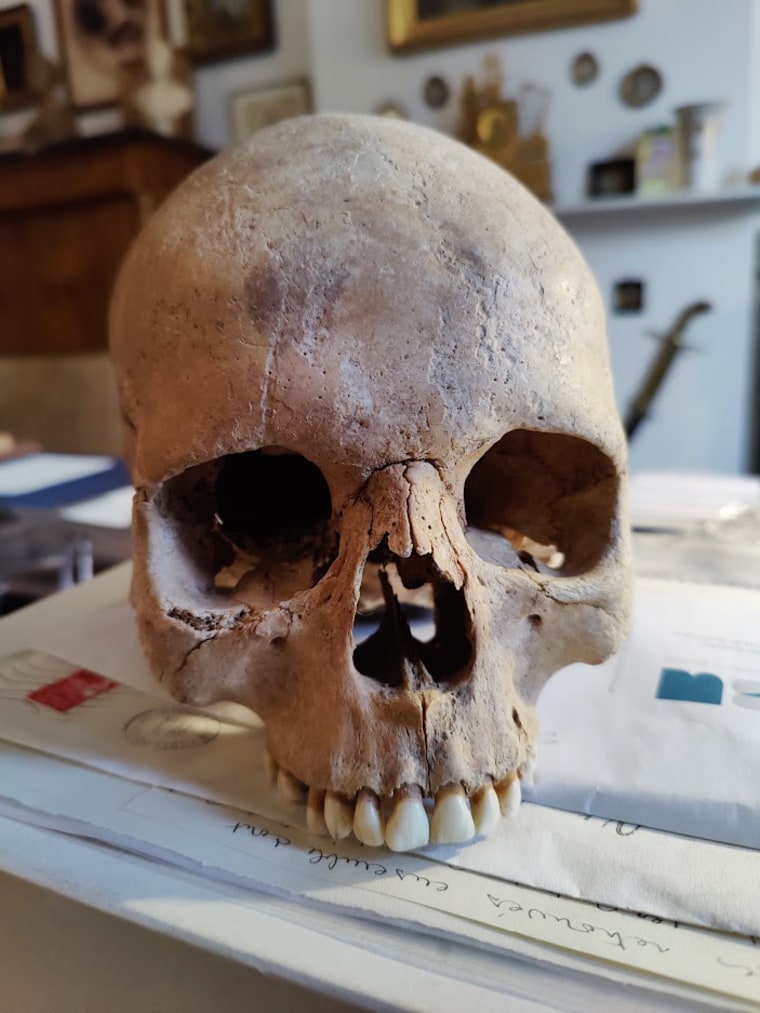

Philippe Boxho, a professor in forensics who examined the bones, also discovered that one of the Prussian soldiers had suffered blunt force trauma around an eye socket, Wilkin said.

“There is quite clearly a sword that went through the eye,” Wilkin said. “The front was probably rammed by the butt of a rifle very violently.”

“I’ve been a historian for 20 years and I work only on battles,” he added. “To look at the soldiers and to then hear the explanation of how they died rather than reading it in a text, it makes a huge difference. I really fell for this poor guy.”

The remains are currently undergoing forensic analysis in the Belgian city of Liège, where Wilkin is based, to confirm the soldier’s identity and provide facial reconstructions of at least one of the skulls, he said.

A spokesperson for Waterloo Uncovered added that they hoped the bones “will be able to shed new light on the dramatic events of the battle and the hardships suffered by those who fought in it.”

[ad_2]

Source link