[ad_1]

Editorial credit: Roman Babakin / Shutterstock.com

By Klaus Heine and Michel Phan

Brand spirit is, or should be, at the heart of a company’s brand culture. But how can a business use this to create cultural meaning and innovation in their brand? Klaus Heine and Michel Phan of emlyon business school present an overview of the process.

Cultural innovations require brands to change their understanding of what is considered valuable. For instance, after embracing top European luxury labels like Chanel and Louis Vuitton for nearly two decades, Chinese consumers are progressively gravitating towards endorsing Chinese luxury brands such as Shang Xia as they strive to showcase China’s rich heritage to the world. At some point, the vibes simply did not resonate any more with many people to practise yoga in Nike or Adidas sportswear. This created an opportunity for Lululemon to provide high-quality athletic apparel focused on yoga, health, and wellness. Victoria’s Secret’s image of glamorous, super-slim supermodels proved challenging to alter and ultimately led to its decline. By embracing the body-positivity movement, the brand lost both its conservative and liberal customers who were sceptical of the shift and preferred more body-positive brands like Aerie and ThirdLove.

The key reason that consumers moved to competitors was not the product quality of Chanel, Nike, or Victoria’s Secret. The reason can be found on a deeper level. New market entrants succeeded with symbolic innovations instead of technological innovations. Viewing innovations as functional achievements ignores the value of identity – and the critical component of many innovations: “bolstering aspects of consumers’ identity” (Holt 2020: 115). Accordingly, cultural entrepreneurs pursue radical cultural innovations, not products (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001).

An effective way to create cultural innovation is to develop a brand spirit, which is at the deepest level of a company’s cultural framework and the source of a big universe of symbolic meaning. While often not formally articulated and sometimes not explicitly perceived by employees and customers, introducing a brand spirit constitutes a pivotal strategic decision that individuals can sense as an organisational atmosphere and specific vibes during interactions with the brand. It provides entrepreneurs with a fast-track route to transforming their brand planning from a blank canvas to a robust brand identity infused with rich cultural meaning.

Why implement a brand spirit

As spirituality is fundamental to human experience, brands with a strong spiritual foundation can connect with employees and customers on a deeper level and can bring profound meaning to people’s jobs and lives. This outcome doesn’t just lead to the ultimate competitive advantage but creates a win-win scenario: employees who are more spiritually engaged tend to exhibit higher motivation, commitment, and productivity. Studies show that companies with high levels of spiritual values outperform those without it. As they are anchored in unspoken mindsets, behaviours, and social patterns, a strong brand spirit also reduces the need for explicit company regulations and control measures.

How to implement a brand spirit

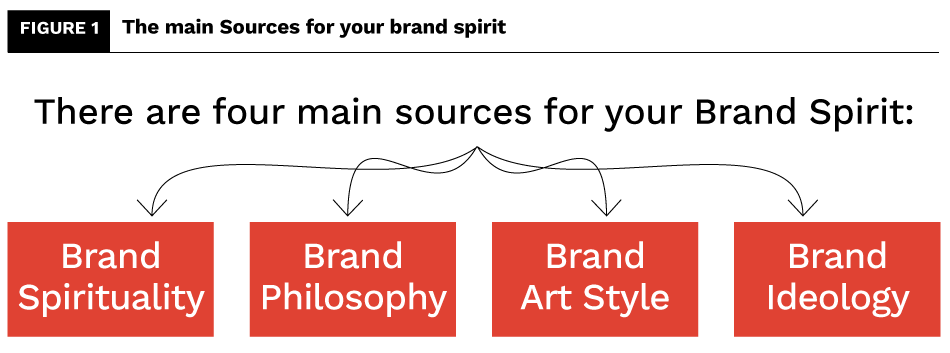

As illustrated in Figure 1 above, there are four primary sources for your brand spirit: brand spirituality, brand philosophy, brand art style, and brand ideology. The following sections present an overview of how to leverage these options.

Brand spirituality: a key to understanding the vibes of Hermès

An effective way to create cultural innovation is to develop a brand spirit, which is at the deepest level of a company’s cultural framework and the source of a big universe of symbolic meaning.

The founder of Hermès was Protestant, and this religious affiliation continues within the Hermès family to this day. This factor strongly influences the company – for instance, the brand’s quest for excellence and understatement. There is a long tradition of Hermès leaders pooh-poohing the term “luxury” because of its perceived arrogance and its hint of decadence. They don’t use celebrities in advertising, they don’t license their name, and there is a maximum salary the CEO can earn. Within the company, there is a strong appreciation of manual labour and craftsmanship, embodying the ethos that “what is beautiful must be useful” (Ellison, 2015).

Why implement brand spirituality

The underlying brand spirit is key to understanding the Hermès brand culture. Especially when compared to Louis Vuitton, visitors to Hermès boutiques can perceive these fundamental beliefs through the distinctive vibes of understated elegance. This orientation guides their brand collaborations with innovators (such as Apple) and traditional brands (like Rolls-Royce), a contrast to Louis Vuitton’s partnerships with trend-focused designers (like Supreme and Jeff Koons). However, many individuals today identify themselves as spiritual but not religious. While religion involves membership in a religious institution, spirituality pertains to an individual’s personal experience. Despite the trend of distancing from organised religion, there is a growing interest in spirituality, leading to the significant expansion of spiritual brands.

The case of Shamballa: the rise of spiritual branding

The men’s jewellery brand Shamballa, from Copenhagen, is inspired by a combination of Buddhism and Nordic myths, craft, and business traditions. This combination exemplifies how to achieve cultural innovation and, consequently, brand differentiation. Making this fundamental yet straightforward decision ensures that the brand is likely to stand out over the long term. The brand purpose is to encourage people to find their inner Shamballa – a state of love, compassion, enlightenment, and wisdom, a mythical kingdom that Tibetan Buddhists believe in. The founders rely on Buddhist philosophies in the way they do business, from early stages of designs to the way they treat employees and interact with the environment. The brand identity revolves around their brand spirituality and makes it a key theme in their brand design and communications. For instance, they embellish jewellery by engraving it with mantras and Sanskrit phrases such as “Om Shanti” (an invocation of peace). Rather than reinventing the wheel with each new collection, they have a wealth of cultural significance to draw upon.

Brand philosophy: how to create brand meaning with depth

The brand philosophy of Shang Xia is rooted in Taoism. This philosophy posits that in a world of opposites, one shouldn’t opt for one over the other, but rather strive to embrace both to achieve balance and harmony. Numerous Western brands create China-inspired collections, often incorporating some of the most recognisable symbols into their designs, including dragons, phoenixes, and Chinese characters. Due to this superficial interpretation of Chinese culture, several Western brands have suffered a backlash as a result of their China-inspired products. Instead of creating products that just “look Chinese”, Shang Xia designers skilfully translate the principles of Taoism into contemporary shapes, proportions, and visual aesthetics.

The benefits of developing a philosophical brand

There is a long tradition of Hermès leaders pooh-poohing the term “luxury” because of its perceived arrogance and its hint of decadence.

More than mere inspiration, Dr Hauschka cosmetics embodies anthroposophy at the core of its brand identity, a philosophy that seeks to nurture the spiritual development of individuals and society. Consequently, Dr Hauschka is renowned for prioritising long-term sustainable management, particularly focusing on social equity and environmental preservation. Distinctive anthroposophical management principles include flat hierarchies, participatory leadership, fair pricing, and the integration of art and culture within the workplace. Establishing a brand on a philosophical foundation enables it to harness pre-existing cultural meaning. Anthroposophical ideas have been employed in diverse domains such as architecture, arts, biodynamic agriculture, medicine, and education. This rich philosophy becomes a resource for various aspects of a company, spanning work organisation, architectural design, workspace layout, training methods, and beyond.

Linking a brand to an art movement

Many strong brands have built some link to the world of art. Tiffany’s iconic style was significantly shaped during the Art Deco era, a resonance that persists in its contemporary collections. Dior’s designs bore the mark of Surrealism, a potent art movement that profoundly influenced his legendary 1947 “New Look” collection. Yves Saint Laurent’s integration of the artistic principles of the De Stijl movement revolutionised the fashion landscape, melding the boundaries between art and attire. What these brands have in common is their utilisation of art movements as implicit foundation. By emulating their example, brands across various categories can draw inspiration from art movements to craft a unique and creative brand identity.

The case of Courrèges

Taking it up a notch, artistic brands position an artistic style as the focal point of their brand identity. A prime example is Courrèges, the Parisian high-fashion house. André Courrèges was a pivotal figure in 20th-century French design and quite possibly one of the inventors of the miniskirt. Inspired by pop art, he inaugurated his fashion house during the 1960s. Characterised by vivid colours, bold outlines, sharp lines, and the incorporation of comic strips and imagery from popular media, the pop art style stands out as instantly recognisable. By entering the pop art culture, Courrèges not only aligned his new brand with the art realm but also tapped into a burgeoning movement that was already captivating a substantial following. Yet, his success relied on the creation of his distinctive “Courrèges style”, a blend of pop art and futurism. An artistic brand places profound emphasis on artistic expression across product design and brand communications. The big advantage of affiliating a brand with an art movement is that it liberates start-ups from the need to construct a distinctive style from scratch, offering a wellspring of creative input and a universe of symbols to draw inspiration from.

But it’s not all about looks

Brands don’t simply adopt an art movement for its aesthetics but, above all, because of its deeper cultural meaning. Your favourite art movement likely mirrors your world view quite closely. Pop art, for instance, surfaced in response to late-1950s consumerism. It was an evolution and, at the same time, a rebellion against Dadaism. One of its key identifying features is the use of images of popular (as opposed to elitist) culture, emphasising the banal elements of consumer culture, often with an ironic undertone. The elevation of everyday objects to high-art status challenged the traditions of fine art and subverted cultural hierarchy. Suddenly, art turned into a commodity. Artists removed images of everyday objects from their context and combined them with other images, to portray the affluence and abundance of post-war society and to play on the themes of consumerism, materialism, and fame. Pop art spread across virtually all facets of society.

The ideas of pop art are reflected in the brand philosophy of Courrèges

An artistic brand places profound emphasis on artistic expression across product design and brand communications.

As an answer to darkness and troubling times, Courrèges promoted his philosophy of “Poptimism” (pop + optimism), along with a sense of positivity and a feeling of liberation, fun and French joie de vivre. He wanted to “make the streets of Paris colourful and pop”. This is expressed by his popular “poor-boy” sweaters and A-line vinyl dresses. He didn’t just speak to the wealthy but wanted to change the world. In the same way as Warhol, he combined luxury pricing and top-class quality with a popular arty dimension and invented the concept of “pop culture luxury” (the initial steps towards the “democratisation of luxury” in the 1990s). Also, today the brand embodies this philosophy, embracing the ethos of pop luxury in stark contrast to the once-arrogant and distant luxury.

Brand ideology: bringing your world view into your business

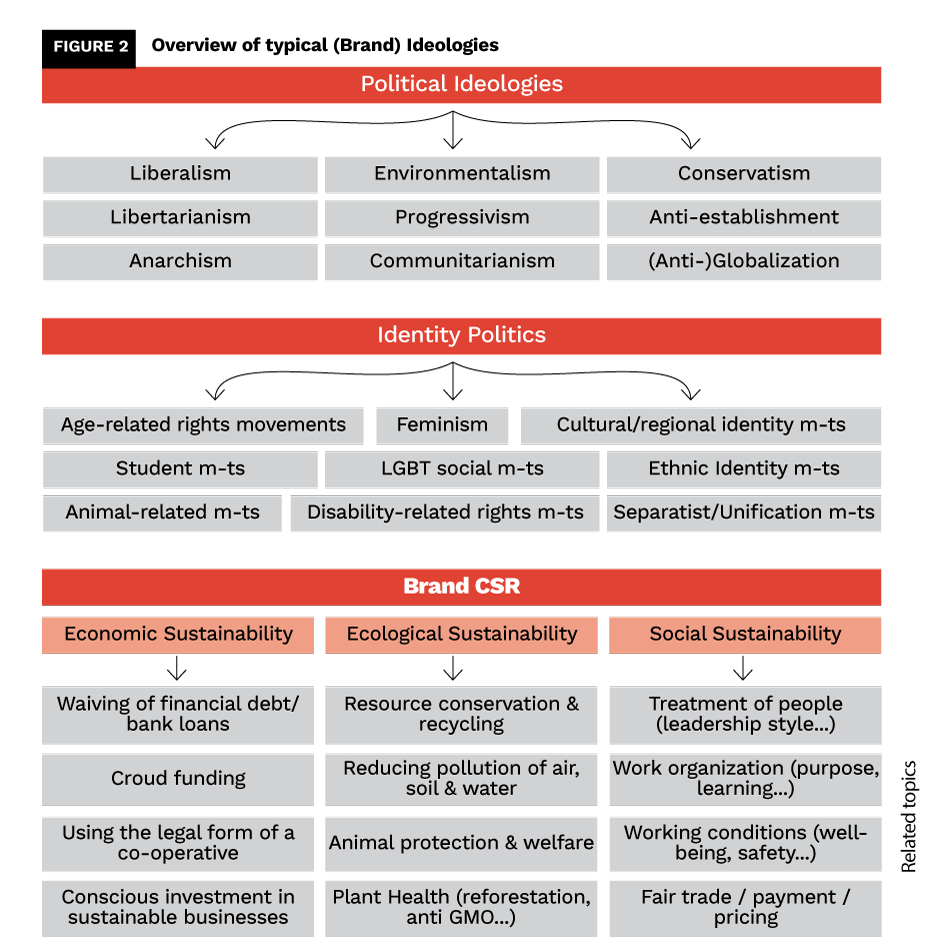

Brand ideology aligns a brand with a well-defined sociopolitical belief system and world view, imparting a distinct sense of identity and purpose. Figure 2 gives an overview of the primary sources for your brand ideology. A brand can be affiliated with a political ideology – think libertarianism (e.g., Tesla), conservatism (Rolls-Royce), or anti-establishment sentiments (Dr Martens). The more common source of brand ideology is identity politics, which includes feminism (Bumble dating app), animal rights (Lush cosmetics), or LGBTQ rights and inclusion (Rebirth Garments).

Another important area of brand ideology is corporate social responsibility (CSR), which aims to align the brand mainly with environmental and societal causes. Veuve Clicquot provides an illustrative example with their overarching CSR theme: the fusion of innovation and eco-friendliness. A key driver of their success is being one of the first to adopt sustainable viticulture practices, dating back to 1990. Another reason is that their constant quest for innovation drives positive consumer and media response. For instance, they started to produce packaging from 25 per cent grape waste. Additionally, they have embraced women’s empowerment as a supplementary CSR facet. While this theme may appear broad for distinct brand differentiation, the secret to success lies in its profound connection to Veuve Clicquot’s brand DNA. Madame Veuve Clicquot took the reins of the maison in 1805, a time when women were denied even the right to hold a bank account, let alone work. Hence, advocating for women’s empowerment seamlessly aligns with Veuve Clicquot’s brand DNA. This commitment came alive through a collaboration with Yayoi Kusama, who reimagined Madame Clicquot’s original portrait with her iconic polka dots for a charitable auction.

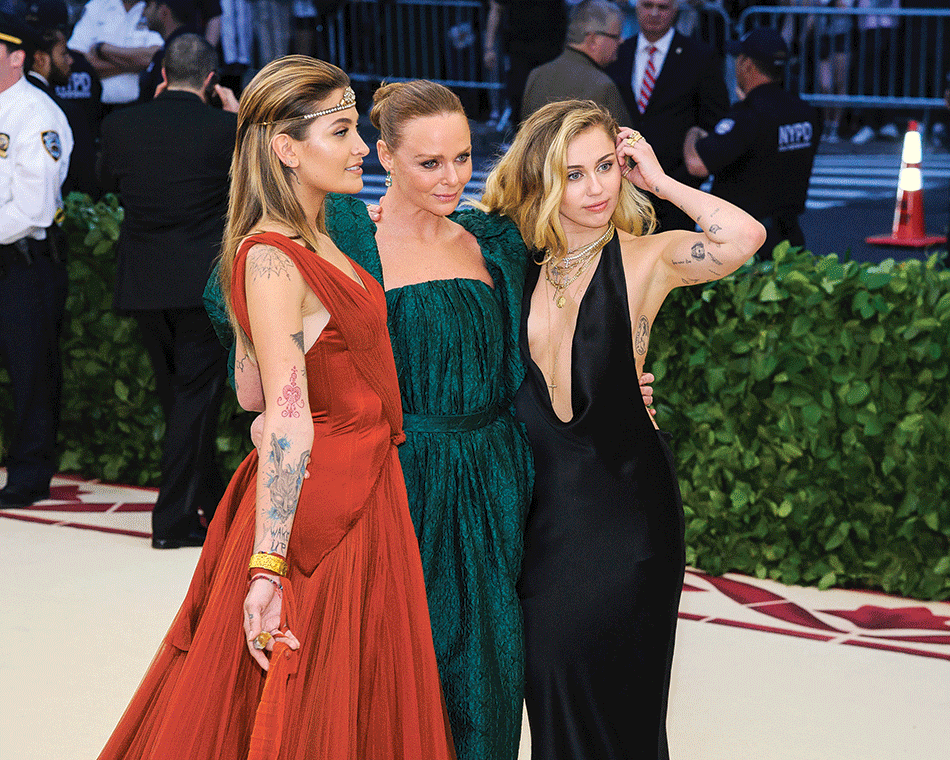

Stella McCartney is an example of an activist brand with a strong reputation for brand CSR. With an unwavering emphasis on “zero percentage animal cruelty”, the designer established a distinct direction and a powerful differentiating factor for the brand. She has never used leather, skins, fur, or feathers in her collections. As a pioneer of fur and leather alternatives and cutting-edge technologies, she pioneered the creation of the first 100 per cent vegetarian fashion brand committed to 0 per cent animal cruelty. Stella McCartney is so closely associated with animal welfare that it almost “owns” this specific brand position in consumers’ minds, at least in the high-end fashion category. Only after achieving this strong position did she incorporate other aspects of sustainability into her brand, such as recycling and responsible sourcing.

Stella McCartney is so closely associated with animal welfare that it almost “owns” this specific brand position in consumers’ minds, at least in the high-end fashion category.

Like many successful entrepreneurs, she has questioned the status quo. Being a lifelong vegetarian, she didn’t simply adopt these ideas since the sustainability trend was in full swing and the public’s applause for anything “sustainable” was guaranteed. Avoiding animal-derived materials was a radical stance she took back in 1997 when she was the artistic director of Chloé, at just 25 years old. At that time, she received criticism and opposition from the mainstream for standing up for her deeply held convictions – and that’s precisely what qualifies her as an authentic change-maker.

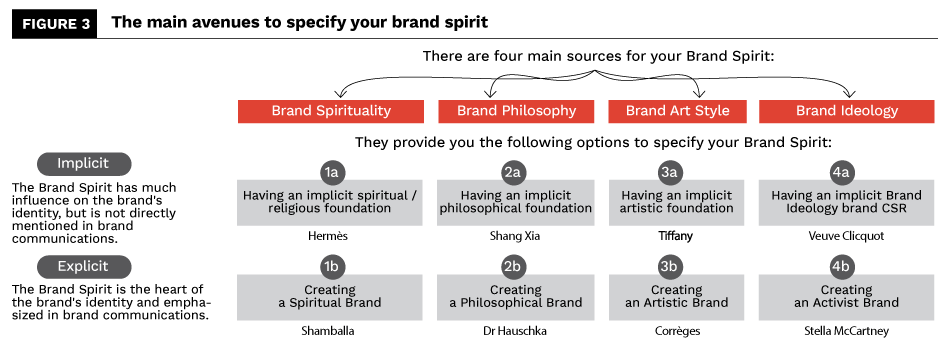

Figure 3 sums up the avenues available for crafting a brand spirit. The brands analysed have used different approaches to explicitly or implicitly integrate a brand spirit into their brand identity and brand communications. Although it might have much influence on the brand’s identity, most brands do not directly mention their brand spirit in communications (represented by the “a” options in Figure 3). Conversely, certain brands place the brand spirit at the heart of their identity and emphasise these ideas in their brand communications (represented by the “b” options in Figure 3).

Figure 3 sums up the avenues available for crafting a brand spirit. The brands analysed have used different approaches to explicitly or implicitly integrate a brand spirit into their brand identity and brand communications. Although it might have much influence on the brand’s identity, most brands do not directly mention their brand spirit in communications (represented by the “a” options in Figure 3). Conversely, certain brands place the brand spirit at the heart of their identity and emphasise these ideas in their brand communications (represented by the “b” options in Figure 3).

Lessons learned: how to create a brand spirit

- Creating a brand spirit is a shortcut to brand meaning. A spiritual, philosophical, artistic, or ideological movement provides “templates for identity construction” as it comes with a subsystem of predefined values and a specific way of life, often accompanied by distinct “taste regimes” and even explicit prescriptions regarding the consumption of clothing, food, entertainment, and other lifestyle aspects (McAlexander et al., 2014: 863). This means that building brand spirit requires just one decision which provides inspiration and direction for most branding measures.

- 2 There is no need to have it all. Most strong brands focus on just one or two of the available options. Trying to cover all of them would dilute the clarity of the brand identity and could lead to consumer confusion.

- Create cultural innovations through unexpected combinations of cultural facets. You can draw inspiration from examples like Shamballa, which combines Buddhism and Nordic myths, or the LA-based fashion brand DÔEN, which combines an artistic style (Californian Vintage) with a focus on women’s empowerment.

- Competitors may be able to copy your design, but they can never copy your brand’s soul. The example of Shang Xia has shown that by copying only a style without believing in the deeper meaning of a philosophy, products can easily look unauthentic. A sound brand spirit makes a brand stand out and isn’t as simple to imitate.

- Select an art movement that maintains some independence from the prevailing Zeitgeist. Just like fashion trends, artistic movements can wane in popularity and eventually become outdated. As seen with the decline of pop art, André Courrèges vanished from the market and was only revived in 2015. Hence, it is worth considering the use of a classic art movement rather than a contemporary one. For instance, the House of Dagmar (ready-to-wear) drew inspiration from Art Deco, a timeless choice.

- To differentiate from competitors, activist brands should concentrate on specific issues. Ideally, they should centre on one primary key issue, accompanied by complementary sub-issues. It is crucial to ensure a strong alignment with the brand’s DNA. For instance, if societal causes like “women’s empowerment” are not deeply connected to the brand’s essence, they may not significantly enhance brand differentiation.

- Take a stance and polarise with your brand. Small and medium-sized companies can make use of a major weak point of big corporations: due to their broad target markets, they are often compelled to conform to the mainstream, whereas a strong brand tribe thrives by challenging the mainstream in some way. Think of the failure of Victoria’s Secret. The winners were start-ups that are built around body-positivity such as Aerie and ThirdLove.

- Even if you don’t intend to establish a brand spirit, it is still valuable to contemplate inspiring schools of thought that can shape your brand. Consider asking yourself which prominent figures align with your brand personality (thinkers, artists, novelists, scientists, etc.). Are there specific books that could serve as sources of inspiration for your brand?

About the Authors

Michel Phan is Professor of Luxury Marketing and Director of Global DBA programmes at emlyon business school. He has carried out consulting work for top luxury companies in France and Asia. He is a regular visiting professor at Zurich University (Switzerland) and Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) in China.

Michel Phan is Professor of Luxury Marketing and Director of Global DBA programmes at emlyon business school. He has carried out consulting work for top luxury companies in France and Asia. He is a regular visiting professor at Zurich University (Switzerland) and Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) in China.

Klaus Heine is a marketing professor at emlyon business school and has collaborated with numerous luxury houses in both Europe and Asia. He helps entrepreneurs to find out what they want their brands to stand for – to build high-end brands with a higher purpose.

Klaus Heine is a marketing professor at emlyon business school and has collaborated with numerous luxury houses in both Europe and Asia. He helps entrepreneurs to find out what they want their brands to stand for – to build high-end brands with a higher purpose.

References

- Heine, K. (2020) Build a Brand to Change your World. Upmarkit Publishing: Tallinn.

- Fournier, Susan and Alvarez, Claudio (2019) “How Brands Acquire Cultural Meaning”, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 29(3): 519-34.

- Holt, Douglas (2020) “Cultural Innovation”, Harvard Business Review, 98(5): 106-15.

- Lounsbury, Michael and Glynn, Mary Ann (2001) “Cultural Entrepreneurship: Stories, Legitimacy and the Acquisition of Resources”, Strategic Management Journal, 22(6‐7): 545-64.

- Sardana, Deepak, Gupta, Narain and Sharma, Piyush (2018) “Spirituality at the Junction of Consumerism: Exploring Consumer Preference for Spiritual Brands”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, vol. 42 issue 6, p. 724-35.

[ad_2]

Source link