[ad_1]

As Silicon Valley Bank UK imploded at the start of March, fintech start-ups were among those scrambling to get money out of the troubled US lender that specialised in funding the technology sector.

“I spoke to their managing director for fintech on Friday noon — he assured me everything was fine,” said one founder. A few hours later, his company had just three months of payroll accessible, with £2mn locked up with SVB UK, the bank’s local subsidiary.

SVB UK’s £1 fire sale to HSBC stabilised the situation, safeguarding deposits. But relief has been tinged with concern that one of the few lenders willing to back innovative start-ups faces an uncertain future, subsumed by a giant of the UK’s banking sector.

Prime minister Rishi Sunak launched a review into UK fintech when he was chancellor, calling for a “digital big bang”. His chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, has since talked about the UK’s “world-beating fintech sector” in a speech envisioning the “world’s next Silicon Valley”.

But fintech founders say that, despite the right noises from government, much more is needed to ensure the UK keeps its pre-eminence in fintech, from unlocking additional funding to reforming listings.

“I think everyone’s a bit jaded,” said Christian Faes, chair of mortgage lender LendInvest, which listed in London in July 2021. “There was no doubt London was the centre of fintech [ . . .] That’s been waning for a number of years.”

SVB UK

Fintech founders emphasised that the HSBC deal was far better than SVB UK going bust. But several raised concerns about how well the culture of the two banks would integrate, given their different risk appetites and backgrounds.

“A lot of founders who said that they’d been rejected recently by HSBC now have accounts with them through SVB UK,” said one investor. “Do they now have to look elsewhere, or is this something that HSBC becomes comfortable with?”

Philip Hammond, a former UK chancellor and chair of crypto firm Copper, also questioned whether HSBC could provide the sort of support needed for riskier early stage companies.

“Businesses are asking themselves whether, for all the rhetoric, it will be possible for that rather distinctive culture [of SVB UK] to flourish inside a behemoth like HSBC,” he said.

HSBC said that it intends to continue to run SVB UK as a standalone entity with no change in its approach to customers, and that the bank will continue to support businesses in the same way it did before the acquisition.

“We have a long history of supporting innovative start-ups in the UK and across the world,” it continued, “and we have always had strong working relationships with venture capital and private equity firms.”

But the future of SVB UK’s customers is not fintech’s only gripe, with some founders drawing attention to uncertainties stemming from the UK’s departure from the EU.

“Tech skills are in short supply, and in some ways it’s limiting the growth potential, particularly for UK fintech,” said Mark Mullen, chief executive of digital bank Atom.

Government Reforms

These challenges are unfolding at a time when growth stocks globally have taken a beating, as rising interest rates and soaring inflation have led investors to search for short-term profits over long-term growth.

Swedish fintech Klarna had its valuation slashed from $46bn to less than $7bn in its funding round last July. UK payments fintech Checkout.com, last valued publicly at $40bn in January 2022, cut its internal valuation to $11bn last December.

“Inflation may not directly impact a fintech business but, if they have to pay 50 per cent more for energy, and consumers are looking to save rather than spend [ . . . ] that’s probably going to filter into fintech activity,” said Nalin Patel, an analyst at PitchBook.

Fintechs are also calling for more sweeping reforms to support growth, such as pushing pension funds to invest a portion of their funds into UK companies, including fintechs.

“There’s a genuine desire in the government for the UK to be a global financial centre,” said Hammond. “but there doesn’t seem to be the willingness to grasp what’s necessary to achieve that.”

Charlie Mercer, head of economic policy at start-up lobby group Coadec, also warned that changes to the research and development tax credit announced by Hunt in the spring statement would prove a particular challenge for fintechs, which are unlikely to spend enough on R&D to qualify.

“Data from our survey of over 250 start-up founders found an average cut of 30 to 40 per cent in funds received, with the average cut of £100,000,” he warned. “This time next year could be bleak for many firms.”

Listings

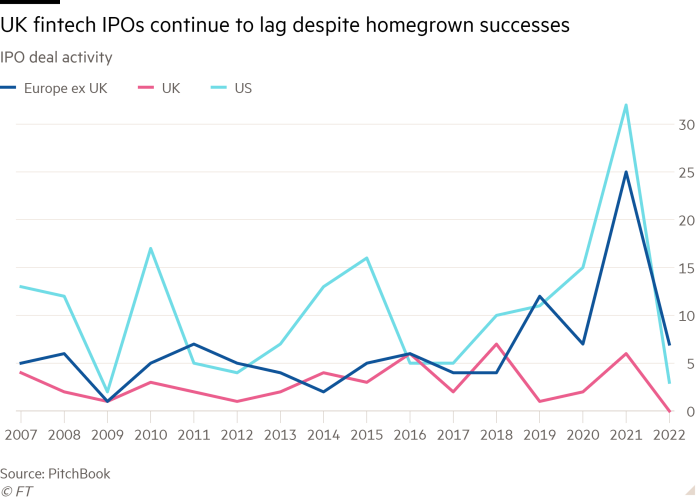

One of the thorniest areas of discussion has been around ensuring that fintechs choose London over other markets when they go public; a debate that companies in other sectors are also weighing.

“You’re just not going to get the same level of investor demand, liquidity and valuation in the UK,” said one fintech executive. British tech giant Arm chose New York over London, with strict rules said to have influenced rejection of UK float.

Ron Kalifa, the former Worldpay CEO, led the fintech review commissioned by Sunak. Kalifa proposed changes such as allowing dual-class share structures to let founders maintain greater control of their companies after an IPO. The government and financial regulators have taken some steps to resolve some issues he raised.

For instance, since December 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority has allowed premium-listed IPOs to have dual-class shares, although they are required to drop the structure after five years.

Another of Kalifa’s recommendations led to the February launch of the Centre for Finance, Innovation and Technology.

Despite these tweaks, Atom Bank’s Mullen said the issues ran deeper.

“The question is whether London is a hub for global businesses and businesses that aspire to be global,” he said. “I’m truly not sure — the noise appears to be drowning out sensible debate.”

[ad_2]

Source link