[ad_1]

Munich’s legendary Oktoberfest is a beer lover’s paradise, with almost 6mn people enjoying its lederhosen-slapping revelry every year. But few of them can guess what is happening 3,000m beneath their feet.

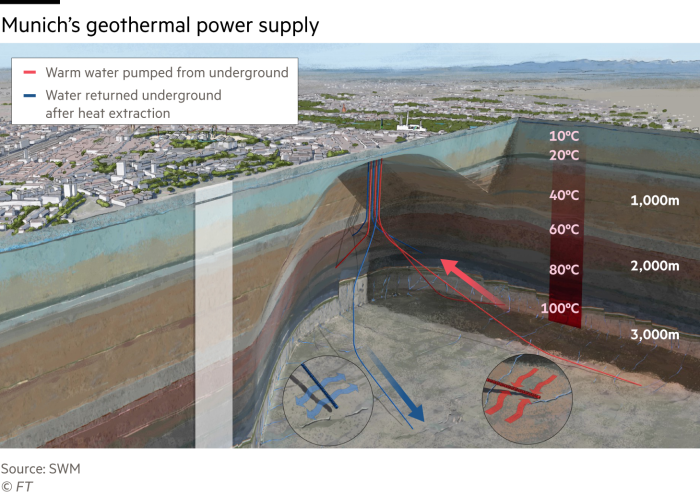

Every day, thousands of gallons of hot water are pumped to Europe’s largest geothermal plant from under the Oktoberfest’s fairground venue, providing heat for 80,000 local people.

“It’s all happening under the Wiesn,” said Christian Pletl, head of renewables at Munich utility SWM, using the local name for the beer festival. “We have a borehole right below it.”

Ever since Olaf Scholz’s government unveiled a law earlier this year banning gas-fired boilers in new houses, the question of how Germans should heat their homes has risen to the top of the political agenda.

The boiler ban was an attempt to address one of the biggest challenges Germany faces in its green transition: the vast amount of CO₂ emitted by its heating sector. Heating accounts for more than 50 per cent of Germany’s energy consumption — and 85 per cent of it comes from fossil fuels.

Scholz’s government must bring this down if Germany is to get even close to its goal of carbon neutrality by 2045.

The ban on new boilers is the centrepiece of those efforts. But another law requiring German municipalities to find climate-friendly energy sources for local heating may prove even more consequential.

Cities across Germany are now frantically trying to figure out how to comply with the new law, which is due to be passed this year. Munich is a step ahead of them.

“Eleven years ago we committed to becoming the first big city in Germany with 100 per cent carbon-neutral district heating,” said Thomas Gigl, head of SWM’s south Munich site. Geothermal energy was “key” to reaching that goal, he added.

Other locations could now follow suit. Rolf Bracke of the Fraunhofer Institution for Energy Infrastructures and Geothermal Systems estimates that deep geothermal could supply as much as 200-400 Terawatt hours (TWh) of energy a year and cover a quarter of Germany’s total demand for heating in its towns and cities.

“Geothermal energy has enormous potential, especially in big cities where there are few other alternatives,” he said. “I’m not going to be able to build a big solar park in the middle of Berlin — I can only go underground.”

The potential for energy extracted from closer to the earth’s surface, between 100m and 1,000m deep, could be even greater. “In theory, 50-70 per cent of the existing housing stock in Germany could be heated using geothermal energy in conjunction with heat pumps,” Bracke said.

The technology is simple: boreholes are drilled into subterranean lakes known as aquifers that lie 1-3km underground. The water is pumped to the surface and its heat passes via heat exchangers to normal, non-thermal water that is then used for heating in residential areas.

“It’s not rocket science. The technology has existed for 150 years,” said Pletl, standing next to huge pipes bringing up 100 litres of water a second at a temperature of nearly 100C from thousands of metres below Munich. “But the real art is in figuring out where to drill — where the porosity of the rock is at its highest and where most of the water is.”

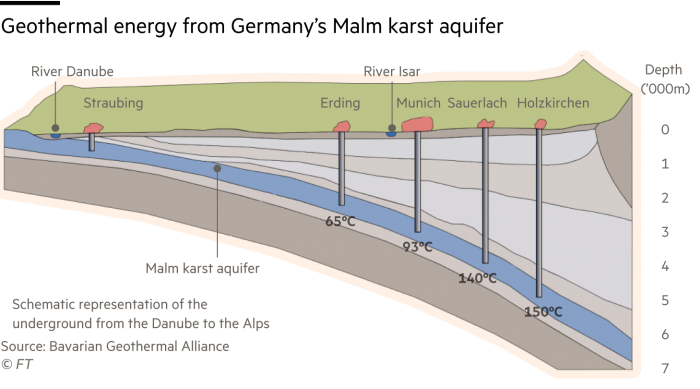

Bavaria’s geothermal story began in 1983 in the small town of Erding, north-east of Munich, when prospectors drilling for oil found hot water instead. Three years later, the local council took over the drill hole and used the water to heat schools, hospitals and industrial zones, as well as to supply a local spa and hot spring.

Twenty-nine more projects followed, all exploiting Bavaria’s Molasse basin, a geological formation stretching across southern Germany. The area is characterised by a thick stratum of fractured limestone through which water can pass.

Bavaria now accounts for nearly 80 per cent of Germany’s installed geothermal power output.

But Bavaria is no world pioneer. Around 250,000 households in France’s greater Paris area receive geothermal heat, fed by aquifers first tapped in 1969.

Iceland is also prolific in the field, with geothermal sources accounting for two-thirds of its primary energy use. Compared with that, Germany is a minnow. In 2020 it had 42 geothermal plants, providing just 359 megawatts of installed thermal capacity, a fraction of total heating demand.

But some experts say the country’s potential is much greater. Hot water aquifers were only found in areas targeted for oil and gas exploration, such as Bavaria, and much of the rest of the country is still uncharted territory.

Bracke said many of Germany’s big metropolitan areas could also have aquifers beneath them, pointing to Aachen near the Dutch border where the Romans created the first geothermal heating network 2,000 years ago.

Berlin is another candidate. In late June the city government announced that it would drill three test boreholes for geothermal energy in the coming months, as part of a drive to cut fossil fuels from the capital’s energy mix.

Meanwhile, a project being launched in Geretsried, Bavaria, by the Canadian company Eavor Technologies, is also garnering attention. Rather than siphoning off water from aquifers, it will circulate water through a U-shaped well, allowing it to be heated naturally by the rock deep underground and brought back to the surface in a “closed loop”.

The advantage of Eavor’s technology is that it can, in theory, be used anywhere, not just in sedimentary basins with underground reservoirs.

But Pletl is sticking to the traditional methods. He expects to be able to continue pumping thermal water out of the aquifers under Munich for years to come. “This resource is virtually inexhaustible,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link