[ad_1]

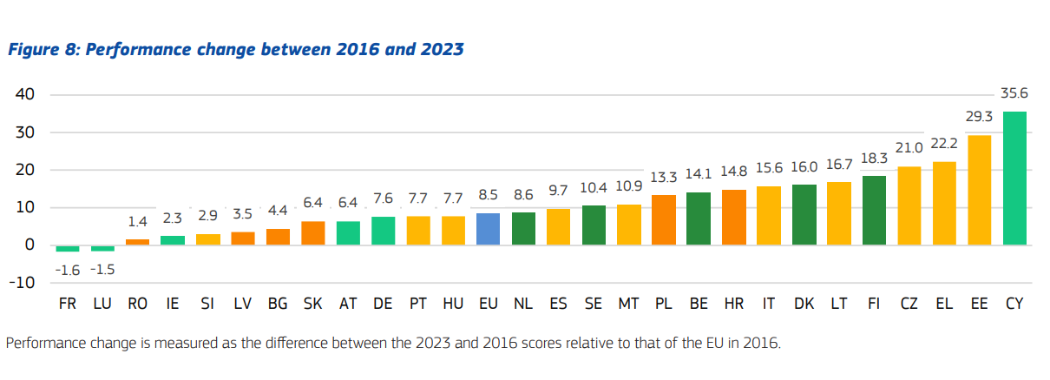

France is one of just two EU countries – alongside Luxembourg – whose overall performance in the European Innovation Scoreboard has slipped since 2016. This is one notable takeaway from the European Commission’s annual report published last week.

Both France and Luxembourg are still ranked as ‘strong innovators’, the second highest classification behind ‘innovation leaders’.

But over the past seven years, France has seen steep falls in areas such as non-R&D expenditure – a broad category that can include funding of equipment, training and marketing, as well as its performance in generating intellectual property, as assessed by the number of patent and trademark applications.

At the same time, R&D expenditure in the public sector has fallen by 4.8 percentage points since 2016, while private sector R&D investment has remained unchanged.

French entrepreneur and CEO of France Multiverse Computing, Michel Kurek, highlighted some issues he has encountered that are contributing to the loss of momentum.

One is the administrative burden on French researchers. Kurek said that in quantum computing, for example, it can take between six months and a year for researchers to get government funding. “I have heard that in Germany, similar funding can be received in two months,” he said.

Beyond the paperwork, French investors are “reticent” about backing new technologies or deep tech. Quantum computing is still seen as an emerging field, and Kurek says this puts off investors in France. “They are not really early adopters,” he said. “I see this in my daily business, when I pitch to big groups […] for them it is too early, they prefer to wait for others to try first.”

Another issue is a lack of private investment, especially in companies attempting to scale-up after initial success. France is trying to address this, with President Emmanuel Macron setting a target of developing 100 French unicorns and creating 500 deep-tech start-ups by 2030.

A recent report by Paul Midy MP suggests one way to increase private funding in the tech sector is by copying the successful UK investment schemes, the Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS) and Enterprise Investment Scheme. Tech companies have got behind the report, and are calling on the government to back its proposals.

A government-commissioned report published last month, also highlights bureaucratic overheads, the complexity of France’s research system, and stagnant funding, as factors that are holding back research and innovation in the country.

Reclassification

A notable change in this year’s Innovation Scoreboard is Hungary moving up from the lowest classification of ‘emerging innovator’ to become a ‘moderate innovator’. This is despite the fact that overall its performance is improving more slowly than the EU average, and it is falling behind better performing countries.

Hungary’s reclassification is related to an improved score in areas such as the number of foreign doctorate students and broadband penetration.

Hungary’s rise was supported by the EU’s Regional Competitiveness Index, published in May this year, which looks at how attractive a region is for companies and residents to work and live. It shows that Hungary as a whole is catching up to the EU average for competitiveness.

Each of the indicators on the Innovation Scoreboard gets equal weighting. In Hungary, broadband penetration is up 22.1 percentage points from 2016 and the number of foreign doctorate students up 120.4 percentage points.

But while these indicators are important aspects of a country’s innovation landscape, they are not the most important, according to Marcel de Heide, senior researcher and economist at Dutch R&D consultancy TNO, and chair of the Impact working group at the European Association of Research and Technology Organisations (EARTO).

“In my opinion, R&D expenditure is way more important than some others,” he said.

On this indicator, Hungary has made more modest improvements, with public sector R&D expenditure up 8.1 percentage points since 2016 and private sector expenditure up 7.7 percentage points. As for government support for business R&D, this indicator is down 58 percentage points since 2016.

Slipping further behind global leaders

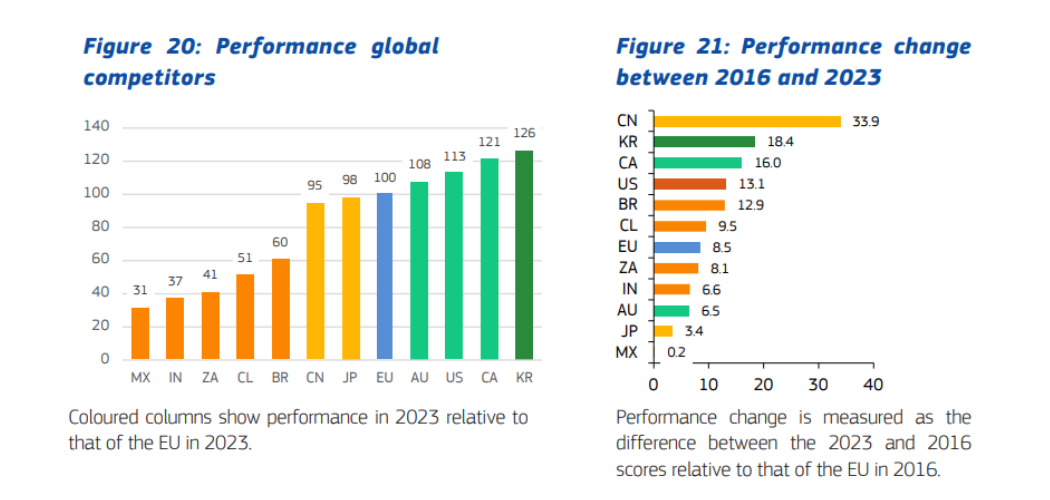

Globally, South Korea is considered the best performing country for innovation, according to the scoreboard. It leads Canada, the US and Australia, with the EU in fifth place. Of these, the EU is improving faster than Australia, but is slipping further behind the other three.

China’s performance is also rapidly improving. Between 2016 and 2023 it gained 33.9 percentage points, far more than the next best, South Korea, which went up by 18.4. China is now only just behind Japan and the EU.

The way the EU approaches research and innovation is different from the US and China, de Heide said. The US and China back R&I almost no matter what,” he said. “In Europe, in the Netherlands for example, there is a tradition of monitoring and evaluating impact and deciding how much should be invested.”

“Whenever there are wider problems, there is divestment in R&D. The US and China trust that there will be an impact, even if it is further down the line,” said de Heide.

The EU needs to put more emphasis on R&I to compete with the US and China and to achieve its targets in the digital and green transitions. A vital way of doing this is through the EU’s €95.5 billion R&I programme Horizon Europe. “We are now bickering about the [Horizon Europe] budget, but that should be the priority for the Commission,” de Heide said. “We shouldn’t care about a few billion euros extra.”

Weakest countries fall further behind

Within Europe the innovation gap between the best and worst performing countries is growing. The weaker countries, with a relative performance below 70% of the EU average, include Romania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia and Croatia.

According to the latest report, these countries are failing to catch up to the moderate innovators.

This highlights a broader trend in the EU of central and eastern European countries trailing their northern neighbours in R&I performance. For de Heide, this is partly to do with the emphasis on funding excellent research, which puts northern European countries at an advantage as their institutions are so experienced in competing for and winning European funding. More focus on knowledge-driven innovation and more support for R&D in regional funds could help address this imbalance, he said.

[ad_2]

Source link