[ad_1]

1. Executive summary

The Cyber Security Academic Start-up Accelerator (CyberASAP) programme is funded by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and delivered by the Knowledge Transfer Network (KTN) [footnote 1]. It supports the commercialisation of UK cyber security research and helps academic researchers to turn ideas into fully rolled-out commercial projects by developing the academics’ entrepreneurial skills. It has two phases as set out in Figure 1:

Figure 1: CyberASAP overview

This evaluation report relates to the CyberASAP programme which was initially piloted in 2017/18 and has been delivered over five years to 2021/22, with one cohort of researchers each year. [footnote 2]

Conclusions and recommendations against each of the core evaluation questions are outlined below.

1.1 Process evaluation

Was the programme delivered as intended?

The programme has evolved each year and delivery has taken place as intended in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between DCMS and Innovate UK.

What worked well, or less well, for whom and why?

There are several examples of elements of CyberASAP that worked well, including:

- the application process as participants indicated they were provided with sufficient information prior to applying for CyberASAP and felt the process was straightforward

- a delivery structure which included a part-time and stage gated process [footnote 3] combined with a digital and hybrid model to support participants with a range of abilities and from a variety of locations

- the provision of support for value proposition, market validation and proof of concept development

- the provision of opportunities for participants to meet and engage with key industry figures and entrepreneurs which resulted in the development of tangible business relationships

- improved entrepreneurial and business management skills

- that those who did not proceed to phase 1(b) or phase 2 still benefited from the programme as it led them to re-think or pivot their idea to a more viable proposition

- the development of a strong ‘community’ who keep in touch and support each other

- that participating teams have successfully attracted investment from a variety of sources, including private business and public sector funds

- 89% (n=47 of 53 survey respondents) feeling their commercial awareness had improved following participation

- the geographical diversity of participants, as shown by 64% (n=35) of the 55 survey respondents being located outside of London and the South-east

There were also several examples of areas for development. This included:

- the need for more time between DCMS funding being confirmed, publishing the call for programme applications and commencing delivery to promote the programme with key target groups

- the need for greater support from university technology transfer officers and flexibility with internal university policies [footnote 4]

- the need for increased linking of the various cyber programmes available

Recommendation 1: we recommend that decisions to fund CyberASAP are communicated at least 9 months in advance (rather than the current timeframe of c. 4 months) to allow sufficient time for programme promotion with potential entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups.

Recommendation 2: we recommend that CyberASAP engages with university Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) to identify potential candidates for the programme.

What can be learned from the delivery methods used? / Were there any unexpected or unintended issues in the delivery of the intervention? / How did external factors influence the delivery and functioning of the programme?

The majority of survey respondents (98%, n=54) were satisfied or very satisfied with the programme structure.

However, COVID-19 limited face-to-face interaction and qualitative feedback suggested this was detrimental to relationship building between participants and with investors. Other factors that impacted delivery across all years of the programme included that:

- academics involved in teaching had limited time to develop their idea / business

- a lack of engagement from the university TTOs restricted awareness and engagement with the programme by academics, and in some instances meant any issues for the university were only raised at phase 2

How can the existing programme be improved to become more effective?

The existing programme could be improved by:

- issuing a thematic call for project proposals focused on market failures in the cyber security sector (in addition to the current format for an open call). This call would be designed to complement other DCMS-funded programmes and external funding calls while also aligning with the needs of industry

- moving delivery of the programme to less busy times of the academic calendar which would improve the programme for participating teams as they are less likely to have teaching responsibilities

- confirming funding earlier in the year or providing funding for more than one year at a time

- improving monitoring and reporting through the development of SMART [footnote 5] targets for all outcome and impact measures in the Theory of Change (ToC)

Recommendation 3: we recommend that SMART outcomes are further developed for CyberASAP and there is detailed reporting on these. KTN to develop based on the CyberASAP ToC metrics and agree with DCMS. Evidence should be collected by KTN for progress against each using both published data and primary research with participants. For example, those noted in the DCMS MoU with KTN for Year 6 and including:

| Outcome measures |

|

Measure 1: number of new cyber security start-ups / spinouts (company registrations) attributed to CyberASAP Evidence source: published datasets |

|

Measure 2: number of viable products or services trialled and attributed to CyberASAP Evidence source: participant feedback via surveys or interviews |

|

Measure 3: increased confidence and skills to deliver cyber security start-ups / spinouts Evidence source: participant feedback via surveys or interviews |

|

Measure 4: increased business survival rates for cyber start-ups / spinouts supported by CyberASAP Evidence source: published datasets |

|

Measure 5: increased investment in cyber security start-ups / spinouts supported by CyberASAP Evidence source: published datasets and participant feedback via surveys or interviews |

1.2 Impact evaluation

The programme has delivered business impacts. To date 108 projects have been supported by CyberASAP [footnote 6] and of these 12 were categorised as spinouts; 2 were acquired by other firms and 5 developed a patent.

The DCMS funding has leveraged £12,382,895 in additional investment (for example corporate / private investment, acquisition, VC investment, angel investment, and seed funding / equity fundraising).

Programme participants were able to meet with organisations, however it will take time to understand the impacts from these meetings and any relationships.

It has also been successful in developing entrepreneurial skills and confidence, including for participants who did not progress to the proof-of-concept stage however completed part (a) or all of phase 1.

To what extent has the programme been successful in commercialising academic research / accelerated the process to commercialisation?

Overall, 26% (n=12 of 47 tracked participants) have spun out companies successfully [footnote 7], some of whom provided their project outputs as an open-source product and through published articles. In addition, survey respondents reported an increased capability to commercialise their research following participation in the programme as:

- prior to participating in the programme 11% (n= 6) of 54 respondents ranked their capability to commercialise research between 8 and 10

- following participation 66% (n= 35) of 53 respondents ranked their capability to commercialise research between 8 and 10 (10 meaning very strong) [footnote 8]

Nevertheless, participants still found it difficult to commercialise their research after the programme had finished and felt that further support is required, either from their university and / or by having further support CyberASAP. Specific examples included ensuring that universities and TTO staff maintain commitment to commercialisation throughout and are as committed to the commercialisation of the Intellectual Property (IP) as the investors. Based on the contribution analysis conducted CyberASAP has had:

- strong contribution to project teams increasing their successful trials and to their business knowledge and skills

- some contribution to the development of new cyber security start-ups or spinouts and short-term investment in these

- negligible contribution to the improvement of participating teams’ ability to enter other incubators and increase input of industry into academia

While 77% (n=41) of the 53 respondents who answered the question had not yet received investment following the programme, some of those will only be at the stage of seeking investment. Therefore, the above contribution analysis is only part of the answer. It will be important to continue tracking progress of the projects after the programme ends to measure longer term impacts.

Recommendation 4: we recommend that the outcomes and impacts from the programme continue to be tracked. It should be a requirement within the delivery partner contract to provide evidence of the capability and business outcomes being achieved for participants at one, two and three years after completing the programme to provide evidence of the longer-term benefits.

We recommend DCMS set up a monitoring template that covers all the outcome and impact measures expected from the programme. This should be completed by the delivery partner for participants when they finish the programme and then at 6, 12 and 24 months after completion.

To what extent does the evidence suggest future funding would be more effective if targeted differently (at less well funded universities, for example)?

The premise of the current CyberASAP model is to attract and identify the most promising commercial opportunities from different parts of the UK academic research base and to make funding opportunities accessible to universities from all regions as well as those outside the Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research (ACE-CSR) and Russell Group.

The project has been successful in achieving this as 82 of the 108 (76%) participating universities from non-Russell Group institutions and 84 (77%) outside of London.

Due to the programme both reaching several non-Russell Group universities and there being a lack of notable difference in outcomes between Russell and non-Russell Group universities (as discussed below), a focus on the best commercial opportunities should remain.

To what extent does the success of the programme differ between different cohorts, types of firm/idea, university?

There is no notable difference in outcomes between cohorts, projects or between universities, including Russell Group and non-Russell Group institutions (with one exception). The only notable variations were:

- Cohort 5 – survey respondents from this cohort reported fewer intended outcomes as identified from the ToC being achieved to date. This is likely due to their more recent completion of the programme compared to preceding cohorts

- Cohort 1 – survey respondents from this cohort reported a greater number of spinouts and receiving further funding. This could be due to (1) having completed the programme c. 4 years previously and (2) the design of the programme in Year 1 meant there was an obligation to spinout/form a company

In addition, there is a similar proportion of the 108 Russell Group and non-Russell Group university projects that are in development, licensed and acquired. [footnote 9] However, a higher difference in the amount of spin-outs achieved was identified between the two groups. KTN feedback suggests this is likely to be the result of Russell Group universities typically being better funded and possessing mature and well-established commercialisation capacities. [footnote 10] This is shown by the proportion of Russell and non-Russell group universities that have:

- reached development stage (Russell Group: 42%; Non-Russell Group 40%)

- spun out (Russell Group: 33%; Non-Russell Group 23%)

- been licensed (Russell Group: 8%; Non-Russell Group 3%)

- been acquired (Russell Group: 8%; Non-Russell Group 3%)

Do participants join other cyber growth programmes after completing CyberASAP?

Evidence obtained from stakeholder interviews indicated that most of the CyberASAP participants who fully completed all phases of the programme did not go on to other cyber growth programmes. Those who did not progress through all stages of CyberASAP tended to either (a) re-apply for CyberASAP; (b) progress to the London Office for Cybersecurity Advancement (LORCA); (c) progress to the Cyber Runway programmes, or (d) access other sources of funding / development programmes. This was in part due to CyberASAP helping them to better understand the schemes available, suggesting the programme plays an important role in the wider cyber growth and innovation ecosystem.

What are the additional or unintended benefits of the programme?

Delivery partner feedback suggests the programme has helped to change the way universities approach commercialisation as some are now more willing to be pragmatic about how much equity they will receive. For example, Royal Holloway University applied a policy which assigned IP to the start-up company in exchange for an under 10% share to make the deal more attractive to investors. [footnote 11] KTN have also suggested the programme is starting to see repeat participation from universities who are beginning to change their approach in this area.

2. Introduction, terms of reference and methodology

2.1 Introduction

RSM Consulting LLP were commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) [footnote 12] to undertake independent evaluations of the CyberASAP, Cyber Runway and UKC3 programmes. The evaluations will help DCMS to understand the impact of these programmes and the findings will be used to inform the development of future interventions.

The CyberASAP programme supports the commercialisation of UK research into cyber security and helps academic researchers to turn ideas into fully rolled-out commercial projects by developing the academics’ entrepreneurial skills. In doing this, it recognises the barriers that academics face when commercialising research, including the lack of dedicated time available to research the market and to validate potential products.

This evaluation report relates to the CyberASAP programme which was initially piloted in 2017/18 and has been delivered over five years to 2021/22, with one cohort of researchers each year. [footnote 13]

The evaluation incorporates delivery and performance across all years to date.

2.3 Methodology

The evaluation methodology was agreed with DCMS and includes the following stages:

Scoping phase

(1) Project initiation meeting: the project commenced with a project initiation meeting involving the evaluation team and DCMS to: (1) review and agree the evaluation methodology and timetable; (2) discuss access to relevant information and (3) finalise arrangements for project management and progress updates.

(2) Desk research and analysis: a review of the strategic and delivery context for the programme and mapping was conducted to identify other sources of funding available to support the commercialisation of cyber security academic research.

(3) Review of programme documentation setting out rationale for funding measures: review of the programme business case; MoU’s between DCMS and Innovate UK; Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) agreed between DCMS, Innovate UK and KTN; and previous research / theories of change relating to the programme to identify the rationale for the intervention and the outputs and impacts expected from it.

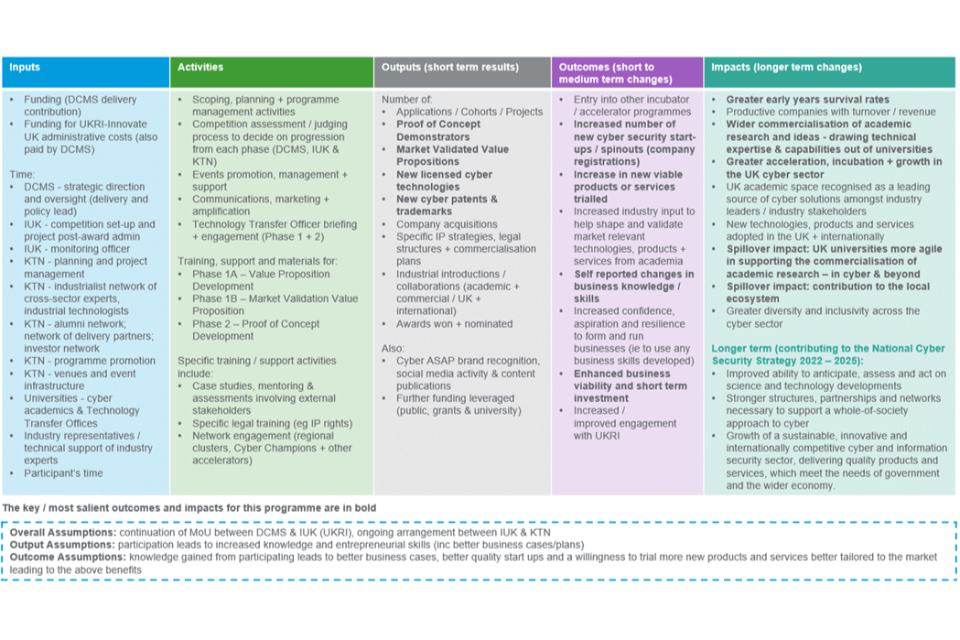

(4) Development of ToC: an online workshop was facilitated with DCMS staff involved in the business case for funding and the design and management of the programme to test and refine the draft ToC and associated metrics. The final ToC (see Appendix B – Theory of Change) was used to inform the research tools that were developed, specifically the participant survey and guides for the participant, delivery partner and case study interviews.

(5) Evaluation plans for each programme: an evaluation plan was developed detailing the design and approach being taken to address the evaluation questions. This was informed by the ToC and outlined how each of the ToC metrics would be measured.

Data collection

(1) Analysis of programme monitoring information / impact information and published data: to inform the assessment of programme performance against its core KPIs (as per the ITT) and those in the agreed ToC.

(2) Surveys and consultations: this involved:

Survey methodology: the survey was designed by RSM UK Consulting in collaboration with DCMS to collect evidence against the key evaluation questions and ToC metrics. As it was not possible for participant details to be shared with RSM UK Consulting without consent, an online survey link was distributed via KTN, with subsequent reminders by email and targeted telephone follow-up to ensure a representative sample across regions and cohorts.

Note: where ‘n=’ is used during survey analysis, it is referring to the number of respondents responding in a certain way / to a specific answer choice, rather than the entire respondent base. Where applicable, a base number has been provided in figure titles or in text to provide more general information on total number of respondents. This base number will occasionally vary from the overall survey participant number of 55 depending on relevance of the question and if respondents choose not to answer.

Participants survey profile:

Table 1: CyberASAP participants respondents by region (base number = 55)

| Region | Sample of CyberASAP survey respondents – frequency | % of survey respondents |

| Scotland | 2 | 4% |

| Wales | 2 | 4% |

| Northern Ireland | 0 | 0% |

| North-west England | 5 | 9% |

| North-east England | 2 | 4% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 2 | 4% |

| West Midlands | 5 | 9% |

| East Midlands | 2 | 4% |

| East of England | 7 | 12% |

| South-west England | 8 | 14% |

| South-east England | 10 | 18% |

| London | 10 | 18% |

Table 2: CyberASAP participants respondents by cohort (base number = 55)

| Cohort | Sample of CyberASAP survey respondents – frequency | % of survey respondents |

| Year 1 | 7 | 13% |

| Year 2 | 15 | 27% |

| Year 3 | 12 | 22% |

| Year 4 | 11 | 20% |

| Year 5 | 10 | 18% |

(3) Counterfactual: nine interviews were completed with those participants successful in applying to phase 1 of CyberASAP but did not proceed to phase 1(b) or phase 2.

(4) Case studies: four in-depth case studies were developed to provide qualitative insight into the benefits of participating in the programme. These were selected to provide a representative sample across regions, cohorts, and stage of idea development and are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Case Studies

| Project | Region (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland) | Cohort (Year) | Stage of development |

| Cydon | England (University of Wolverhampton) | Year 2 | New company established |

| PriSAT | Scotland (University of Glasgow) | Year 3 | In development |

| Secure development | England (Lancaster University) | Year 4 | In development |

| WalletFind | England (University of Salford / Bristol / Manchester Metropolitan) | Year 5 | In development |

Analysis and reporting

- analysis of monitoring data for each programme by sector, geography, university, and cohort: to assess performance against targets and to identify variations between cohorts, universities, and cyber security sectors

- contribution analysis: this focused on why the results have occurred and the role played by CyberASAP; it involved 2 key steps:

(1) based on the ToC, 6 contribution statements were developed describing the outcomes CyberASAP intends to achieve and how

(2) based on the data collected in the previous stages the strength of evidence was assessed against each contribution statement, as well as evidence of any other factors that have contributed

The strength of evidence was determined by reviewing:

- clarity

- frequency of a particular theme

- diversity of the stakeholders who provide the evidence (across cohorts)

- emphasis placed on the evidence by stakeholders

- examples of how the stakeholders know about the evidence they report

- availability of the evidence across primary, monitoring and Management Information (MI) data

High strength of evidence includes:

- evidence that is articulated clearly and frequently by different stakeholders without the need for probing

- where the survey findings show high rates of “strongly agree / disagree” and similar responses across different measures

(3) The contribution of CyberASAP to the expected results as described by each contribution statement was assessed as strong, some, or negligible, with:

- strong contribution meaning that CyberASAP’s activities contributed substantially to the observed results

- some contribution meaning that CyberASAP’s activities contributed to the observed results but not substantially

- negligible contribution meaning that CyberASAP had no or minimal contribution to the result

Reporting: included a progress presentation, interim and final reports, a final presentation, and a closing workshop with DCMS which will act as a learning event.

Limitations

Counterfactual: it was not feasible or appropriate to contact those who were unsuccessful in their application to the CyberASAP programme to form a counterfactual group as their characteristics were too dissimilar to complete a robust regression discontinuity analysis – based on information provided by KTN – due to:

- their project being out of scope

- too little information being provided to make an assessment

- some of the application questions not being answered

- finances being incorrect within the application (for example, applied for too much)

The absence of a robust counterfactual means that caution should be applied to over interpreting the results of the impact evaluation, in that it is not possible to rule out the possibility that some of these impacts will have occurred under the counterfactual.

Therefore, it was agreed with DCMS that a qualitative counterfactual approach would be applied by completing interviews with participants who did not complete all phases of the programme in order to identify what they did instead and if / how the programme impacted on this.

3. Rationale and programme overview

This section details the strategy and delivery context, and the rationale for the CyberASAP programme, as well as providing an overview of other programmes in this space.

3.1 Review of the strategic and delivery context

3.1.1 Policy

The CyberASAP programme was expected to contribute, or has the potential to contribute, to several key national strategies, as set out below.

Table 4: Strategic context

| Strategy | How the CyberASAP programme is expected to contribute |

|

National Cyber Security Strategy (2016 – 2021) – supports the creation of a growing, innovative and thriving cyber security sector in the UK

National Cyber Strategy 2022 – focuses on strengthening the UK Cyber Ecosystem |

The CyberASAP programme was expected to contribute to this by supporting the commercialisation of innovation in academia and providing training and mentoring to academics that will help to ‘create a cyber ecosystem in which cyber start-ups proliferate, get the investment and support they need to win business around the world [and], to provide a pipeline of innovation that channels ideas between the private sector, government and academia’

While the CyberASAP programme was designed before the National Cyber Strategy 2022 was developed, it contributes to the objective of fostering and sustaining sovereign and allied advantage in the security of cyberspace-critical technologies through ensuring the UK becomes “more successful at translating research into innovation and new companies in the areas of technology most vital to our cyber power.” |

|---|---|

| DCMS UK Digital Strategy (2022) | The CyberASAP programme could contribute to one of the key actions within this strategy to ‘generate ideas and IP’ as it supports the successful development and commercialisation of new ideas. In addition, the Digital Strategy includes a focus on spreading digital prosperity and levelling up, and CyberASAP contributes to this by: • attracting and identifying the most promising commercial opportunities from different parts of the UK academic research base • making funding opportunities accessible to universities from all regions and to those outside the ACE-CSR and Russell Group |

3.1.2 The UK cyber security sector growth and innovation space

The UK cyber security sector is growing rapidly as outlined in the UK Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis published in 2022. This is shown by:

- approximately 52,700 full-time equivalents working in the cyber security sector (a 13% increase from the previous year, of which 64% work in large firms with over 250 employees)

- an estimated revenue of £10.1 billion (an increase of 14% compared to the 2021 publication)

The UK has a reputation as a global leader in cyber security research, with 19 ACE-CSR, four Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council – National Cyber Security Centre (EPSRC-NCSC) Research Institutes, four Centres for Doctoral Training, the Centre for Security Information Technologies (CSIT) and the PETRAS National Centre of Excellence in Cyber Security of Internet of Things (IoT). he 2022 UK Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis also notes that investment in cyber security firms has increased, with over £1.4 billion being raised in 2021 across 108 deals. In addition, the sector is playing a critical role in responding to emerging cyber threats and challenges, and the rapid proliferation of connectable products.

However, research in 2020 found that long-term investments in other nations, especially the USA, France and Germany, are leading to the development of large clusters of research excellence. This can pose a threat to maintaining the UK’s position as a leading nation for research and innovation in cyber security, given a potential brain drain from the UK. It suggests a need for the UK to further invest in cyber security research in various forms, including clusters of research excellence in cyber security; doctoral research funding to train future research and development (R&D) leaders in cyber security; and national research facilities.

The UK Innovation Strategy highlights that UK universities have become more effective at attracting investment and bringing ideas to market in recent years and of the top ten universities ranked by levels of funding raised by spinouts, the UK has five. However, this trend needs to be expanded beyond a small group of research-intensive UK universities, ensuring that technology transfer skills and expertise of a broader range of universities are enhanced to make the sector more accessible for investors.

The challenges within the sector and the innovation landscape include:

- investment being skewed to larger companies – start-ups and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) receive considerably less investment than larger, more established firms and the 2022 Sectoral Analysis found that 85% of the total 2021 investments targeted large-medium firms

- a regional divide in the cyber security sector – for example, 33% of job postings are in London, with only 2% in Wales and according to the 2022 Cyber Sectoral Analysis, 53% of Cyber Security firms are registered in either London or the South-east, with only 2% of the firms in Northern Ireland

- the UK no longer having access to EU cyber security funding – this would have amounted to approximately €1.65 billion (available across the entirety of Europe) over the period 2021 to 2027 [footnote 15]

- difficulty commercialising academic research into cyber security – as it faces barriers related to access to funding, ability to dedicate time to market research and validation, and the need to balance teaching, research and commercial activity [footnote 16]

- the sector not being diverse – the cyber security skills in the UK labour market report for 2022 highlights that 22% of the cyber security workforce is female (compared to 30% across the digital sectors as a whole), but ethnic minorities make up 25% of the cyber security sector workforce, which is higher than 12% in the overall workforce, and 15% in the digital workforce, that ethnic minorities represent [footnote 17]

3.1.3 Mapping of other programmes

CyberASAP is part of a wider ecosystem of cyber security growth and innovation programmes across different stages of the ‘innovation pathway’.

Figure 2: Cyber security growth and innovation programmes

CyberASAP is the first ‘stage’ in the innovation pathway focused on pre-seed and proof of concept ideas. It supports the commercialisation of UK cyber security research into fully rolled-out commercial projects. It is complemented and followed by programmes that support companies at different stages of the business lifecycle to:

- Launch – to support the establishment of new companies in the sector by helping to transform early-stage cyber security ideas into workable proposals and potential new businesses (programme: Cyber Runway Launch)

- Grow – to support existing SMEs in the early and growth stages of the life cycle to improve the survival rate of early-stage cyber businesses (programmes: NCSC for Strategy, Cyber Runway Grow and LORCA)

- Scale – to support cyber security scale-ups to address barriers to growth nationally and internationally (programmes: LORCA and Cyber Runway Scale)

These interventions are also complemented by other government and private sector initiatives with a cyber security element, illustrated in the following table.

Table 5: Mapping of other programmes

| Project name | Target group | Funders and funding | Expected outcomes |

| Knowledge Transfer Partnership (KTP) | A KTP is a partnership open to a UK-based business or not-for-profit organisation and university, college or research and technology organisation. | Partnerships are part funded by grant, however businesses also have to contribute to the cost of the project. A typical KTP project delivers a support package valued at £80,000 – £100,000 per year. [footnote 18] | KTPs connect forward thinking businesses with knowledge bases to deliver business led innovation projects. The academic will work with the business to develop the project with academic input, while also recruiting a suitable graduate to the business to support with the project. |

| UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) commercialising quantum technologies challenge | Companies and projects involving products/technologies based on advances in quantum science. | UKRI is investing £153 million, supported by £205 million from industry. [footnote 19] | This competition aims to develop new products and technologies based on advances in quantum science. The challenge will comprise four areas to support the UK quantum industry. This includes: product and service innovations, industry-led technology development projects, supply chain feasibility projects, and an investment accelerator. |

| UK-Singapore Collaborative R&D | UK businesses looking to collaborate on R&D projects | Innovate UK will invest up to £3 million in partnership with Enterprise Singapore, with each individual project able to apply for a maximum grant of up to £350,000 (funding applies from September 2022 – August 2025). [footnote 20] | This competition aims to fund business led collaborative R&D projects focused on industrial research, with cyber security specifically identified as a sector that they would particularly welcome applications from. Proposals must include at least one partner from the UK and one partner from Singapore and demonstrate a disruptive innovative idea leading to new products / processes / services. |

| Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund (ISCF) digital security by design – software ecosystem development | UK registered organisations | UKRI investing up to £8 million in R&D projects (each project can request a total grant from £200,000 – £1.4 million, with funding applying from April 2022 – December 2024). [footnote 21] | The competition aimed to fund a range of projects that work to enrich and expand the Digital Security by Design (DSbD) software ecosystem prior to the availability of commercial hardware. The funding is from the ISCF. |

There are several programmes available to support innovation within the UK’s wider cyber security ecosystem. However, there are no other initiatives focused primarily on the pre-seed, concept stage as, while Cyber Runway Launch aims to support the establishment of new companies in the sector, CyberASAP’s main focus is on addressing the challenges faced by academics in the commercialisation of research.

3.2 Programme overview and funding

3.2.1 History / background to the programme

The CyberASAP programme was initially set up as a pilot in 2017 based on research by KTN into barriers for the commercialisation of research in cyber security. The programme’s development is outlined in the following table.

Table 6: CyberASAP development – summary

| Year | Summary |

| Year 1 (2017) | The initial pilot was an Innovate UK funded programme, delivered by the SetSquared partnership. Year 1 was developed initially incorporating the Innovation to Commercialisation of University Research (ICURe) model [footnote 22] as the source of training. KTN provided additional business training to support projects in the development of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) [footnote 23] and delivered a showcase / demo day at the end of the programme in October 2017. |

| Year 2 (Programme Design, 2017 and delivery 2018-19) | Working with the leads from DCMS and Innovate UK; KTN led a review and workshopped a new programme based on the feedback from teams and insights gained by DCMS and Innovate UK through the Year 1 programme. This new programme split the activities into commercial proposition development stages, with an external selection panel comprised of industry experts assessing the projects before they moved to the next stage. In addition, a range of personal development skills were introduced as appropriate for each stage of the programme. The Year 2 programme removed the obligation to spinout / form a company at the development grant stage as it was identified that the projects required more support and further development. |

| Year 3-5 (Delivered over each financial year 2019-2022) | The programme was further developed based on cohort, alumni and industry feedback. In Year 5 the programme was opened to participants of the Security of Digital Technology at the Periphery (SDTaP) programme. Grant funding for SDTaP was from an Innovate UK budget (UKRI Strategic Partnerships Fund) and programme running costs were shared with DCMS. The programme content was the same for the DCMS and SDTaP projects. [footnote 24] |

Source: Information provided by KTN to RSM UK Consulting (February 2022)

The evaluation incorporates delivery and performance across all years to date.

3.2.2 Programme delivery

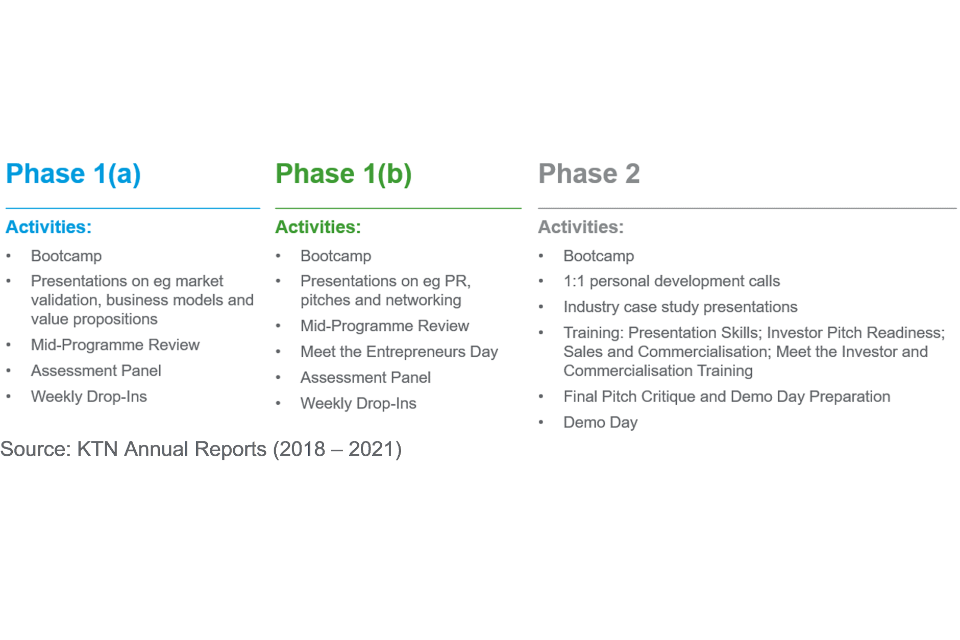

The programme has consisted of two phases based on a similar structure used in the ICURe programme, the proof-of-concept phase was added after the pilot year as it was felt this was missing in the original ICURe model. This included the:

- development of value proposition and market validation by academics – phase 1(a) and phase 1(b)

- development and demonstration of a proof of concept by the most promising projects (phase 2)

A two-stage selection process is used to both (1) ensure there is a wide selection of ideas and universities involved and not only those ‘most likely to succeed’ and (2) for industry experts to filter out those that do not have a robust idea / concept that is viable to take forward to phase 2.

Figure 3: CyberASAP overview

3.2.3 Key outcomes / impacts expected

The initial ICURe pilot programme had a simple set of KPIs. This included:

- supporting the creation of at least 5 trading entities or licensing agreements

- recruiting 6-7 possible concept demonstrator teams for phase 2 funding and progress to demo day

- delivering a programme of monitoring and support for the selected teams

- creating and delivering a programme of business planning, development and mentoring

From Year 2 these were developed further as KTN introduced a logic model to measure the social and economic impacts of the programme based on Year 2 activities and programme design. Key programme objectives included (based on the 2021/22 delivery year):

Figure 4: CyberASAP Year 5 (2021/22) objectives

4. CyberASAP process evaluation

This section details the CyberASAP programme governance structure; key stakeholders; the application process; how the programme is delivered; and reporting requirements. It focuses on assessing whether the programme was delivered as intended and what could be improved in delivery.

4.1 Governance structure

In Year 1 (2017) the delivery partners were:

- Year 1 (Phase 1) SetSquared (as part of the ICURe programme) – focused on delivery of the support programme & management, and funding to university teams

- Year 1 (Phase 2) SetSquared (as part of the ICURe programme) – focused on management & payment of funding to university teams

- Year 1 (Phase 2) KTN – focused on delivery of the business support programme

The governance structure for the CyberASAP programme in Years 2 – 5 is outlined below:

Figure 5: CyberASAP governance structure (Years 2- 5; 2018 – 2022)

Roles and responsibilities

The following table provides further detail on the roles and responsibilities of each organisation.

Table 7: Roles and responsibilities

| Organisation | Role / Responsibilities |

| DCMS | DCMS manages: • funding – provides funding to Innovate UK for administrative costs; KTN costs and delivery costs • attendance at events in an observatory capacity |

| Innovate UK | Innovate UK manages: • the funding of the delivery partner, KTN, who are delivering the complete programme to the academic teams • the funding of payments & monitoring of the academic teams via their universities through a standard Innovate UK grant-funded competition Specifically: • project management – in accordance with UKRI-Innovate UK’s standard operational procedures, and its corporate policies – review progress of the programme at regular intervals with DCMS – meet quarterly with DCMS – ensure that programme management includes sufficient focus on the evaluation of benefit forecasts, with appropriate teams and resource consulted to deliver an effective evaluation strategy as part of the management of the programme • contracting – with KTN to deliver the CyberASAP programme • reporting – providing DCMS with financial and monitoring reports |

| KTN | Innovate UK contract KTN to deliver the programme content. They are responsible for devising and delivering the programme via: • bootcamps • training • tools • mentoring • peer to peer learning • an industry showcase (demo day) • KTN have delivered the programme from Year 2, taking over the role from the SetSquared partnership after the first two phases of Year 1 were completed as part of the ICURe programme |

Source: DCMS and Innovate UK MoU (2021)

4.2 Programme delivery

4.2.1 Key phases / stages

Design [footnote 25] – KTN discusses proposed changes and evolution of the programme year-on-year in collaboration with DCMS and Innovate UK before submitting a formal proposal to Innovate UK and DCMS in December / January containing a plan for the next programme.

Delivery – in all years there has been a single call for applications / competition and intake per year. [footnote 26] Further information on delivery includes that:

- in Year 2, the competition opened in January and the programme commenced in February, running until the following January

- for Years 3-5 the programme has been delivered within a single financial year; broadly the competition opens in February / closes early March and delivery is from April until the following February, with minor adjustment to dates as needed for operational reasons

- each year the delivery and completion of the programme has taken place as planned (there has not been any slippage/rescheduling of planned dates)

4.2.2 Communications and promotion

KTN communicated and promoted the programme in several ways, including via:

- a social media strategy

- Twitter and LinkedIn accounts

- the in-house KTP advisors who support the KTP programme (a KTP connects universities and UK businesses meaning the KTP advisors cover all UK universities)

- a dedicated communications lead / KTN communications team

- a dedicated events lead who worked with the communications lead and the core delivery team to ensure that all activities were promoted and supported (this included the promotion of competition and wider events)

KTN also maintains a year-round general ‘expression of interest’ in the programme which is used to promote the competition when it opens. Between Year 3-5 of the programme, KTN also introduced weekly online (Zoom) drop-ins for participants and alumni, as well as an alumni newsletter highlighting opportunities for grants, investment, event participation and new programmes. They also introduced an alumni tracking programme to facilitate and encourage alumni engagement.

While the programme is promoted in several ways, delivery partner feedback highlighted this is hindered by the lack of certainty regarding funding for the next year or programme. It is not known until approximately November or December each year if the programme will be funded for delivery the following April, leaving a short time frame from publishing the call to receiving responses and assessment. It was suggested that if it were possible to market the programme earlier (for example, from June in the preceding year) there could be a greater focus on addressing any regional, diversity or gender target by engaging with organisations in these areas, exemplified by those supporting women in cyber.

CyberASAP participant findings:

Awareness of the CyberASAP programme

Awareness of the programme from participants was mainly through their university (31%, n=17 were first made aware of the programme in this way). Both other researchers and KTN were the next most common sources of information (24%, n=13). This highlights a clear emphasis on these three information streams for raising awareness of the programme. No respondents indicated they became aware of the programme via print / social media, suggesting these approaches may have been less worthwhile.

Figure 6: How participants became aware of CyberASAP (base number=55)

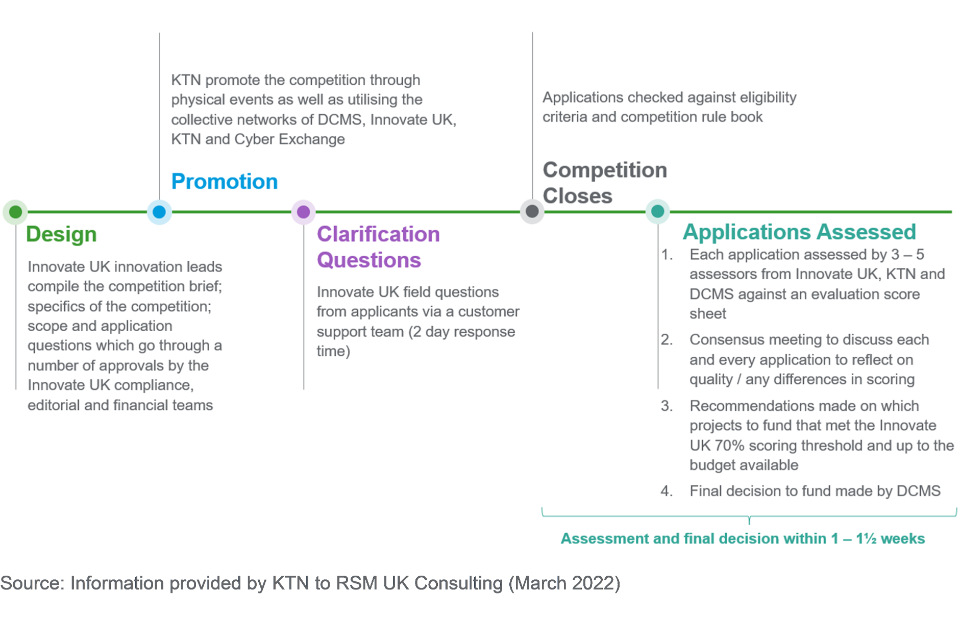

4.2.3 Application process

Eligibility

The most recent CyberASAP programme eligibility criteria includes the following:

Figure 7: CyberASAP eligibility criteria (2021/22)

All individuals based in a UK academic institution are eligible, including but not limited to early career researchers and senior academic researchers. KTN have noted that the criteria were intentionally wide-ranging, reflecting the nature of cyber security.

Changes which have been made to the eligibility criteria over the duration of the programme have focused on having the support of the TTO within the university, specifically: [footnote 27]

- in Year 3 it was emphasised that applicants had to have the support of their university, as there were issues in year 2 with projects having applied without informing their university

- for Year 4 onwards it was a requirement that the TTO, or equivalent, is named on the application form to try to ensure that they are involved

- for Year 5 onwards KTN are trying to directly engage with the TTOs rather than relying on the academic project leader to do this, including holding briefing events for them

Process

The application process for Phase 1 was via a standard Innovate UK grant-funded competition. Teams were assigned a monitoring officer to support the project management, reporting and finances. This approach has been consistent from Year 2 onwards. In Year 5 the programme piloted a challenge-led approach [footnote 28] and incorporated SDTaP university projects. The application process for the SDTaP university projects was almost identical to that for other teams, with the SDTaP projects indicating if they were applying for the SDTaP cohort or the open cohort. Following this phase:

- projects were assessed by external industry-led panels and only projects that passed proceeded to phase 1(b)

- applications to Phase 2 were via a closed Innovate UK competition focused on the development of a proof of concept; feedback is provided by Innovate UK to those who are unsuccessful at the end of Phase 1(a) and 1(b). A summary of the initial application process is illustrated in figure 8

Figure 8: CyberASAP application process – phase 1

CyberASAP participant findings:

Application processes

Participant survey responses suggest they were provided with sufficient information prior to applying for CyberASAP, specifically:

- 60% (n=33) of the 55 survey respondents strongly agreed and 29% (n=16) agreed that the right amount of information was provided

- 96% (n=53) of the 55 survey respondents felt the application process was straightforward

However qualitative feedback highlights information they would have liked to have been provided with prior to participation, with the most common theme being an increase in information provided around programme structure:

A bit more detail on how the programme is structured would have been useful.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

A bit more advice on the role of the three major stages – value proposition / market validation / commercialisation.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 2 – 2018/19)

4.2.4 Support provided

Each phase commences with an online 1–2-day bootcamp, followed by intermediate training and other sessions, and ends with a formal assessment panel for which the teams submit reports and / or presentations in advance. The exception is Phase 2 which ends with a demo day where the teams pitch and demonstrate their proof of concept to an invited audience of investors and industrialists. In Year 4 and 5, in line with the online delivery of this event, the teams prepared pitch videos and demonstrator videos for their proof of concept. As a condition of the grant award, project teams are expected to attend the scheduled activities.

Figure 9: CyberASAP – activities overview

In Year 4 provisions were included by KTN, supplementary to contract due to a surplus budget as a result of fewer events being held due to COVID-19. This included:

- weekly online drop-ins throughout the programme (April 2020 – February 2021)

- R&D Tax Credits Webinar

- proof of concept demonstrator videos for each project – fully edited

- pitch videos for each project – support for recording and creation from media contractor

CyberASAP participant findings:

Most participants stated they felt support was available for value proposition development (77%, n=37), market validation (71%, n=34) and proof of concept development (52%, n=25).

Figure 10: Participants perceived availability of support throughout the programme (base number = 48)

However, Table 8 shows fewer respondents were satisfied with the support provided for proof-of-concept development, specifically:

- 60% (n=29) of 48 respondents were very satisfied and 35% (n=17) were satisfied with support for value proposition development

- 54% (n=26) of 48 respondents were very satisfied and 33% (n=16) were satisfied with support for market validation

- 33% (n=15) of 45 respondents were very satisfied and 36% (n=16) were satisfied with support for proof of concept development

In addition, the majority of participants (98%, n=54) were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall structure of the programme (the provision of support for the three aspects listed above).

Table 8: Participant satisfaction in areas of the programme where support was provided (base number = 48) [footnote 29]

| Answer choice | % Very satisfied | % Satisfied | % Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | % Dissatisfied | % Very dissatisfied | % Not sure N/A |

| Training for value proposition development | 60% (n=29) | 35% (n=17) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4% (n=2) |

| Materials for value proposition development | 56% (n=27) | 38% (n=18) | 2% (n=1) | 0% | 0% | 4% (n=2) |

| Support for value proposition development | 60% (n=29) | 35% (n=17) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4% (n=2) |

| Training for market validation | 60% (n=29) | 33% (n=16) | 2% (n=1) | 0% | 0% | 4% (n=2) |

| Materials for market validation | 56% (n=27) | 33% (n=16) | 6% (n=3) | 0% | 0% | 4% (n=2) |

| Support for market validation | 54% (n=26) | 33% (n=16) | 4% (n=2) | 2% (n=1) | 0% | 6% (n=3) |

| Grant funding (n=46) | 37% (n=17) | 41% (n=19) | 9% (n=4) | 2% (n=1) | 0% | 11% (n=5) |

| 2-day bootcamps (n=47) | 51% (n=24) | 38% (n=18) | 4% (n=2) | 0% | 0% | 6% (n=3) |

| Selection panel assessments (including Q&A and feedback) | 50% (n=24) | 35% (n= 17) | 10% (n=5) | 0% | 0% | 4% (n= 2) |

| Mentoring sessions | 46% (n=22) | 44% (n=21) | 6% (n=3) | 0% | 0% | 4% (n= 2) |

| Industry showcase demo day | 50% (n=24) | 35% (n= 17) | 13% (n=6) | 0% | 0% | 2% (n= 1) |

| Peer-to-peer learning (n=47) | 43% (n=20) | 32% (n=15) | 15% (n=7) | 0% | 0% | 11% (n=5) |

| Legal training (including IP training) (n=46) | 28% (n=13) | 35% (n=16) | 26% (n=12) | 0% | 0% | 11% (n=5) |

| Training for proof of concept development (n=47) | 36% (n=17) | 40% (n=19) | 13% (n=6) | 0% | 0% | 11% (n=5) |

| Materials for proof of concept development (n=46) | 30% (n=14) | 33% (n=15) | 22% (n=10) | 0% | 0% | 15% (n=7) |

| Support for proof of concept development (n=45) | 33% (n=15) | 36% (n=16) | 16% (n=7) | 0% | 0% | 16% (n=7) |

4.2.5 Data and reporting

Innovate UK provide DCMS with monitoring reports each quarter. Each report includes an overall rating for the programme, progress on deliverables, recommendations for the quarter and any other actions that may need to be taken. It also provides a view on the extent to which benefit forecasts are being realised and highlights actions to resolve any issues preventing the realisation of identified benefits.

Data collected to date by KTN for in-programme delivery has mainly focused on key output statistics such as application numbers and universities engaged, among others, and on confirming that projects have participated in the planned activities. In addition to the in-programme delivery reporting, KTN has tracked CyberASAP programme graduates. This has included the development of an impact and insights report as well as several 1–2-page case studies on key projects. A CyberASAP website (microsite on the KTN website) has also been developed to showcase graduated projects. From Year 5 DCMS introduced a monthly logframe report which includes:

- a cover sheet with a brief narrative overview of progress

- a financial report

- KPI and milestone progress

- a risk register and guidance on the risk register

KTN and Innovate UK populate the report, which is then reviewed by the DCMS Programme Manager on a monthly basis with a follow-up discussion. DCMS feedback suggests the logframe reports provide all the information required to effectively oversee delivery of the programme, including risks and progress against the KPIs agreed in the MoU and no action has been required to address underperformance.

The logframe format was introduced to standardise financial and performance data being collected across several DCMS programmes and to align with onward reporting requirements to Cabinet Office and DCMS central finance. Areas for development include:

- the development of specified targets for all KPIs (the contract between DCMS and Innovate UK does not specify targets and instead notes a number of qualitative milestone objectives which the logframe report indicates as either completed, delayed or not complete)

- an explanation of why any delays occur

The monitoring approach could be strengthened by:

- formulating SMART targets for each KPI

- providing narrative information about progress against the milestones

- providing targets for milestones – this would be especially valuable where delays occur so that these can be understood

It may be useful to consider if key outputs or outcomes from the programme could be incorporated in regular reporting through the logframe, including:

- the number of proof-of-concept demonstrators

- the number of market validated value propositions

- new licensed cyber security technologies

- the number of cyber trademarks or patents

These are core ToC outputs which would improve reporting on milestones for each of the CyberASAP phases, without being onerous for programme teams to provide the relevant information.

In addition, there is currently no requirement for alumni engagement and follow-up. While KTN have completed work in this area as a result of underspend in 2020/21, consideration should be given to ongoing and regular follow-up as the alumni group continues to grow in order to demonstrate longer term impacts, for example at 6 months, 1- and 2-years post completion.

CyberASAP participant findings:

Reporting processes

The majority of CyberASAP participant survey respondents highlighted they were satisfied or very satisfied with the frequency of reporting; amount of information they needed to provide; and clarity of reporting requirements.

Table 9: Participant’s assessment of the reporting arrangements on CyberASAP (base number= 54)

| Answer choice | % Very satisfied | % Satisfied | % Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | % Dissatisfied | % Very dissatisfied | % Not sure N/A |

| Frequency of reporting | 31% (n= 17) | 43% (n= 23) | 13% (n= 7) | 9% (n= 5) | 2% (n= 1) | 2% (n= 1) |

| Amount of information to provide | 31% (n= 17) | 39% (n= 21) | 19% (n= 10) | 7% (n= 4) | 2% (n= 1) | 2% (n= 1) |

| Clarity of reporting requirements | 37% (n= 20) | 41% (n= 22) | 11% (n= 6) | 6% (n= 3) | 2% (n= 1) | 4% (n= 2) |

This is also reflected in the qualitative feedback provided:

Something that massively helped was that the reports were entirely in line with what we would need to compile to get the company progressed anyway – it was not “busy” work but rather the genuine and progressive output from the project which was reported. I found checking in with the MO was also useful as a focal point for making sure I had everything together.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

The reporting seemed just about right, not too onerous. Having someone to speak to (even if it was just a short meeting that was needed) was very useful.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 5 – 2021/22)

4.2.6 Factors impacting on programme delivery

The impact of external factors on programme delivery

Views on the impact of COVID-19 on programme delivery were mixed with 49% (n=26) of the 53 respondents indicating COVID-19 had not impacted delivery at all, while 43% (n=23) suggested it had a moderate to large impact. However, qualitative feedback suggests the impact of COVID-19 in reducing face-to-face interactions was detrimental to relationship building:

There’s less interaction among participants and also with the organisers of the programme.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

The main impact of COVID-19 was not being able to meet with the CyberASAP team and the other teams in the competition

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

The entire programme was run remotely. This affected the ability of the cohort to build stronger cohesion and limited networking possibilities. Although the CyberASAP team has done an amazing job at keeping activities captivating and agreeable and have been available as much as needed for the cohort.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

This was also reflected in feedback from participants who did not progress through the full programme who referred to the benefits of informal and constructive discussions with other participants and stakeholders between seminar discussions. However, they also noted that teaching while developing their idea / business was one of the most notable external factors hindering progression as CyberASAP was run alongside academic requirements.

What worked well in programme delivery

Qualitative feedback from participants highlighted a key benefit of the programme was its ability to provide opportunities for participants to meet and engage with key industry figures and entrepreneurs, which has led to tangible business relationships:

The meet the entrepreneur days – excellent insight and feedback from the experts, it was a unique and informative experience.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 3 – 2019/20)

The people involved in the programme: not only the organisers, but also the people invited to give talks and presentations.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

Participants also valued the skills development training provided, with survey respondents noting that the programme had developed their entrepreneurial (85%, n=46 of the 54 respondents) and business management (56%, n=30 of the 54 respondents) skills. This is also illustrated in the qualitative feedback received on how the programme had impacted on their development:

Skills development – especially market validation, value proposition, and presentation in a commercialisation context.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 2 – 2018/19)

Training on managing a sales funnel was superb.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

What worked less well in programme delivery

Feedback from participant survey respondents suggests they would like greater support from their university TTOs with Figure 11 showing that 37% (n=20) felt they only received a small level of support and 24% (n=13) feeling TTOs had not helped at all. Qualitative feedback from several participants highlights that their universities did not have a technology transfer team or equivalent to support them.

Figure 11: Assessment of support provided by universities and their TTOs (base number= 54)

At the time we didn’t have a proper tech transfer officer…

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 3 – 2019/20)

At the time the university did not have a dedicated technology transfer officer, however they supported [me in] exiting the university to run the business.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 1 – 2017/18)

In relation to issues participants encountered during programme delivery, the most common was internal university policies. This, combined with the lack of positive impact regarding university TTOs, highlights the need for improvement in this area.

Figure 12: Issues encountered during participation in CyberASAP (base number= 54) [footnote 30]

This was also reflected in delivery partner feedback which indicated TTOs within the universities had not sufficiently engaged with the programme, meaning any issues were only identified at a later stage during Phase 2 (in relation to IP, for example). In addition, it was suggested that technology transfer officers would be an efficient way to raise awareness of the programme in all universities across the UK (Russell and non-Russell group) rather than the delivery partner contacting academics directly.

While only 20% (n=11) of the 54 respondents felt there were gaps in delivery, key themes highlighted by those who provided further detail included a lack of preparation for life after CyberASAP, and specifically the key issues facing newly formed companies. For example qualitative feedback includes:

Further training on the development and management of a start-up company could be a great add-on.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 5 – 2021/22)

More insight into a company formation process would be useful.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 2 – 2018/19)

Information on how different share types work in a new company.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 3 – 2019/20)

What improvements could be made to programme delivery

In relation to how the programme could be improved, 16% (n=8) of the 50 free-text responses referred to an increased emphasis on funding for participants and 55% (n=29) of 53 respondents suggested that grant funding was insufficient to achieve the maximum benefits for their projects. Qualitative feedback on potential improvements included:

The grant for phase 2 was insufficient (less than advertised).

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 3 – 2019/20)

Increased funding to extend the scope of the proof-of-concept outcomes.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

Follow up funding after proof of concept.

CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 2 – 2018/19)

Extra financial support to get printing and business planning.

CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 4 – 2020/21)

4.3 Summary of key findings

The programme has been delivered effectively with positive feedback and high levels of satisfaction from participating academics on the application process and support provided at each stage for their value proposition, market validation and proof of concept development. Participants valued the opportunity to meet and engage with key industry figures and entrepreneurs and highlighted the training undertaken had led to personal development in key areas for commercialising research, including entrepreneurial and business management.

While COVID-19 impacted on programme delivery, this was mainly in relation to relationship building and not the quality of training / support provided. However, key issues which participants highlighted as a barrier to their participation and progression included commitments to teaching while developing their idea / business, the lack of support from their TTOs and internal university policies. Each year the delivery partner has tried to increase the engagement of the technology transfer officers with universities and while this has developed to an extent, participant feedback suggests there is still a need to get greater university ‘buy-in’ to the programme.

5. CyberASAP impact evaluation – performance

This section provides an overview of the performance of CyberASAP against its KPIs, delivery objectives, and outputs as specified in the programme ToC. The sources used are based on monitoring information which KTN and Innovate UK submit to DCMS, including logframe reports. [footnote 31]

5.1 Participants

The following diagram provides an overview of participant numbers for each phase of the programme in each year (no targets were set for each phase):

Figure 13: Participants for each phase of CyberASAP 2017 – 2022 [footnote 32] [footnote 33]

Of the 108 participating universities for which data is available [footnote 34] 82 (76%) are from non-Russell Group institutions and 84 (77%) are from outside of London. The following table outlines the proportion of non-Russell Group and non-London based participating universities over the 5 years of the programme. This shows that while there has been some fluctuation between years, non-Russell Group and non-London based participants have always represented the majority in each year, peaking at 87% and 92% respectively.

Table 10: Proportion of non-Russell Group and non-London based participating universities (base number= 108)

| Cohort | Proportion of non – Russell Group participating universities | Proportion of non – London based participating universities |

| Year 1 | 61% | 92% |

| Year 2 | 81% | 77% |

| Year 3 | 87% | 80% |

| Year 4 | 68% | 71% |

| Year 5 | 73% | 73% |

5.2 Performance against KPIs

This section assesses performance against the delivery partner contracted KPIs based on data submitted in the logframes to DCMS (note: in years 2017 – 2020 no formal monitoring KPIs were set).

Table 11: Performance against KPIs

| Indicator / Target | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| 1 Teams progressing through programme phases [footnote 35] | Target: N/A Actual: 12 |

Target: N/A Actual: 26 |

Target: N/A Actual: 26 |

Target: N/A Actual: 28 |

Target: 20 Actual: 21 |

| 2 Running total investment attracted by CyberASAP projects / companies (£) [footnote 36] | N/A | N/A | Target: N/A Actual: Year 1-3, over £3.2 million (cumulative total as of 2019) [footnote 37] |

Target: N/A Actual: Year 1-4, over £7.5 million (cumulative total as of 2020) [footnote 38] |

Target: N/A Actual: Year 1-5, £17.2 million (cumulative total as of March 2022) [footnote 39] |

| 3 CyberASAP Alumni Companies registered (running total) [footnote 40] | Target: N/A Actual: 9 |

Target: N/A Actual: 9 |

Target: N/A Actual: 14 |

Target: N/A Actual: 20 |

Target: N/A Actual: 22 (as of February 2022) |

| 4 CyberASAP articles published [footnote 41] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Target: 12 (for whole year) Actual: 33 (as of March 2022) |

Source: CyberASAP Programme logframe (March 2022, Year 1-4 Annual Reports, Year 5 final logframe, KTN data provided to RSM UK Consulting LLP.

The latest logframe report (March 2022) and Year 1 to 4 Annual reports indicate that CyberASAP has met its KPIs. The logframe also tracks whether delivery milestones as per the MoU between DCMS and Innovate UK are on track as planned. As of March 2022:

- most delivery milestones for CyberASAP were met

- the only delivery milestone that was not completed as planned was ‘CyberASAP Year six programme confirmation’, i.e. confirmation of whether the programme would continue into its sixth year; this milestone was planned for November 2021 and completed one month later in December 2021

- milestones relating to the Year 6 programme were delayed (specifically: competition promotion, publishing, opening and closing) as DCMS were waiting for the outcome of the Year 3 spending review before proceeding, however are now complete

The logframe does not specify targets for the running total (£) attracted by CyberASAP projects / companies or CyberASAP alumni companies registered.

Feedback from delivery partners suggests while the monitoring and ToC KPIs are helpful to work towards, it is not clear if the KPIs are ambitious or stretching enough as there is no baseline evidence to measure against.

5.3 Performance against the Theory of Change

5.3.1 Activities and outputs

The activities and outputs conducted and achieved over Years 1 to 4 [footnote 42] based on KTN annual reports include:

Table 12: Activities and outputs

| Year | Activities | Outputs |

| Years 1-4 | • selection panels and application assessments • bootcamps and webinars • concept demonstrators / showcase events • events such as: Meet the Entrepreneurs Day, Information Security Europe Show • training such as: presentation skills, sales and commercialisation, meet the investor |

• 123 applications, 92 projects • 47 Demonstrator events • 20 companies formed • over £7.5 million in investment secured over Years 1-4, including by private businesses, from EU grants, and Innovate UK • over Years 1-4, at least 3 projects joined HutZero. Other projects joined: IoTWales, BetaBen, Cyber101 (at least 5 projects) |

| In addition to the above: | ||

| 1 | • business plan development | • demonstrator showcase events for each project in Phase 2 (7 – 6 from original Year 1 cohort, and 1 that joined from ICURe) |

| 2 | • pre-announcement registration of interest phase to promote programme | • market validation phase participation by 17 projects • 1 project shortlisted for funding from the Mayor of London’s Civic Innovation Challenge |

| 3 | • pre-announcement registration of interest phase to promote programme • Twitter activity and publication of articles • alumni conference |

• market validation phase participation by 20 projects • Years 1 to 3 total: three patents registered and three companies who have provided their project outputs in open source format • one project received £200,000 in spinout support from Scottish Enterprise, and another secured £50,000 in funding from Innovate UK to develop a mobile app |

| 4 | • pre-announcement registration of interest phase to promote programme • Twitter activity and publication of articles • alumni conference • 1:1 Persona Development Calls |

• 20 market validation projects |

Across the five years participating teams have successfully attracted investment from a variety of sources, including private business and public sector funds (such as EU grants or Scottish Enterprise support). Other participants have spun out companies successfully, some of whom provided their project outputs as an open-source product and through published articles.

5.3.2 Outcomes

Entry into other incubator / accelerator programmes

The majority of 53 survey respondents (79%, n=42) had not participated in other programmes aimed at supporting the commercialisation of research into cyber security since completing CyberASAP. Of those who had, most (67%, n=6 of the 9 who provided detail on the programmes accessed [footnote 43]) noted they had accessed other external accelerator programmes.

In addition, most of the participants interviewed who did not progress through the full programme continued onto other programmes, applied for other funding, or decided to reapply to CyberASAP. The other schemes reportedly accessed included:

- ICURe run by SetSquared Partnership

- Scottish Funding Council

- Enterprise fellowship

- LORCA

- Cyber Runway

- Defence and Security Accelerator

- Innovate UK funding

- CyLon

- RCUK (research funding EPSRC)

- university accelerator programmes

Increased number of new cyber security start-ups / spinouts (company registrations)

The following two tables detail the current status and outcomes of all CyberASAP participants from Cohorts 1 – 4 based on data provided by KTN (Cohort 5 data was not yet available). This shows a similar proportional performance between Russell Group and non-Russell Group universities, however a higher number of Russell Group university projects are in development, spun out, licensed and acquired. As shown in Table 14, non-Russell Group projects constitute the majority of those that have raised investment and participated to other accelerator schemes.

Table 13: Current status of participating companies from both Russell Group and non-Russell Group universities (Year 1 – 4)

| Status | Number from Russell Group universities (base number=12) | % of total Russell Group universities in the programme (i.e. what % of the Russell group universities spun out or in development | Number from non-Russell Group universities (base number=35) | % of total non-Russell Group universities in the programme (i.e. what % of the Non-Russell group universities spun out or in development) |

| In development [footnote 44] | 5 | 42% | 13 | 37% |

| Licensed [footnote 45] | 1 | 8% | 1 | 3% |

| Spun Out [footnote 46] | 4 | 33% | 8 | 23% |

| Acquired [footnote 47] | 1 | 8% | 1 | 3% |

| Unsure [footnote 48] | 0 | 0% | 6 | 17% |

| Dormant [footnote 49] | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% |

| Abandoned [footnote 50] | 1 | 8% | 5 | 14% |

Source: CyberASAP Alumni Status Tracking (March 2022) provided to RSM UK by KTN

Table 14: Current outcome of participating companies from both Russell Group and non-Russell Group universities (Year 1 – 4)

| Outcomes | Number from Russell Group universities (base number in brackets) | % of total Russell Group universities in the programme (i.e. what % of the Russell group universities raised investment) | Number from non-Russell Group universities (base number in brackets) | % of total non-Russell Group universities in the programme (i.e. what % of the Non-Russell group universities raised investment) |

| Raised investment [footnote 51] | 8 (n= 30) | 27% | 22 (n= 30) | 73% |

| Patent granted [footnote 52] | 2 (n= 4) | 50% | 2 (n=4) | 50% |

| Other accelerators scheme accessed | 7 (n = 17) | 41% | 10 (n= 17) | 59% |

Source: CyberASAP Alumni Status Tracking (March 2022) provided to RSM UK Consulting by KTN

There were mixed findings in relation to the programme’s ability to support an increase in company registrations/spinouts with 49% (n=23) of 47 participant survey respondents who answered this question stating their company’s spinout is fully, or partly, attributable to CyberASAP while 51% (n=24) did not feel that CyberASAP was attributable to this process.

However this may be partly due to insufficient time post-CyberASAP to deliver in this area as qualitative feedback includes:

Much of the above is in progress. We only finished CyberASAP in February 2022. We are in the process of moving invention reports to patent applications. We are applying for funding to help with the spinout process.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 5 – 2021/22)

[COVID-19] meant all my efforts had to be turned to online teaching which meant I have had no time to commit to developing the business further. I am only now just starting to look at picking this up again.

– CyberASAP survey respondent (Cohort 3 – 2019/20)

Table 15: Has CyberASAP been impactful in supporting participants’ business development process? (base number=51) [footnote 53]

| Answer Choice | Yes | Yes, partly | No |

| I have spun out a company (n=47) | 36% (n=17) | 13% (n=6) | 51% (n=24) |

| I have licensed IP from my research (n=46) | 17% (n=8) | 17% (n=8) | 65% (n=30) |

| My product or service has been acquired by another firm (n=47) | 9% (n=4) | 4% (n=2) | 87% (n=41) |

| My company has been acquired by another firm (n=46) | 4% (n=2) | 2% (n=1) | 93% (n=43) |

| I have secured further funding (n=48) | 25% (n=12) | 19% (n=9) | 56% (n=27) |

| I have employed more people (n=47) | 21% (n=10) | 4% (n=2) | 74% (n=35) |

| My company is more productive (n=46) | 22% (n=10) | 11% (n=5) | 67% (n=31) |

| My company’s turnover has risen (n=44) | 11% (n=5) | 5% (n=2) | 84% (n=37) |

| I have made my technology open source (n=46) | 15% (n=7) | 4% (n=2) | 80% (n=37) |

Case Study – Cydon: commercialising academic research

About Cydon

Cydon is an academic start-up company. Their product is a decentralised data management platform which allows regulation of data sharing across organisational boundaries and supply chains. [footnote 54] They applied to the CyberASAP programme through the University of Wolverhampton and were part of the second cohort of the programme. They have now filed a patent in both the UK and USA.

Probably as academics, we all think of things from the academic point of view and knowledge prior to the programme was restricted as we didn’t know how to take it to the commercial side/business side.

When they began the CyberASAP programme, Cydon was just a project. The academics hoped that the programme would enable them to spinout and knew that receiving commercialisation support was the best way to achieve that.

While one or two other support programmes existed, the entry requirements prohibited them from qualifying, in relation to IP and government clearance. They found CyberASAP to be more inclusive and easier for them to “tap into training and resources.”

Support received from CyberASAP

The academics describe the support they received from CyberASAP as “endless” as it covered a comprehensive range of topics in several different formats. They recall a variety of useful training sessions around topics such as market analysis, sales and IP. There were handouts provided and slides that contained lots of commercial content vital for developing a business from an initial research idea.

As well as the benefit of funding, the academics felt that the most useful part was receiving training that helped academics think with a commercial mindset. They said that lots of support was provided around this during sessions at various times throughout the year.

Attending commercial events such as Infosec and presenting in front of investor panels gave them a platform to increase awareness of their academic research and the potential business that could be developed around it.

We had to create an elevator pitch during programme and commercial planning which was extremely useful.

People from the programme have been described as “very contactable” as the academics felt they were thoroughly supported with follow up questions and issues. The academics said that the CyberASAP team were very responsive especially around business modelling and IP. They found additional support on these aspects to be of great value.