[ad_1]

Transnet and Eskom, the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) responsible for South Africa’s economic malaise, have descended into a deeper leadership and governance crisis with an exodus of executives in recent weeks.

Eskom has not had a group CEO since February after the resignation of André de Ruyter, and its board is now doing further interviews to fill the position.

The Eskom board has its own problems. The chairman, Mpho Makwana, resigned suddenly this week after just 13 months in the post. He was immediately replaced by Mteto Nyati, who became Eskom’s seventh board chair since 2011.

Mteto Nyati becomes Eskom’s seventh board chair since 2011. (Photo: Business Day / Freddy Mavunda)

Nonkululeko Dlamini, the Transnet chief financial officer, who has left. (Photo: Fani Mahuntsi / Gallo Images)

There has also been a leadership shake-up at Transnet, the rail and port operator. Portia Derby, the CEO, and Siza Mzimela, head of the rail division, are on their way out. Nonkululeko Dlamini, the chief financial officer, has also left.

Eskom and Transnet have been left more rudderless at a time when their inefficiency is causing huge losses to the economy and public finances.

The SA Reserve Bank estimates that Eskom blackouts (especially higher stages) are costing the economy R899-million a day in shuttered factories, closed shops and malfunctioning infrastructure.

Stellenbosch University estimates that the country is losing R1-billion a day as a result of the dysfunction at Transnet. Trains are delayed or not moving at all, and its ports are ranked among the world’s worst in efficiency, container loading and waiting times.

Fixing Eskom and Transnet has become urgent for the country.

Daily Maverick asked former board members of SOEs about the reasons behind the mess at Eskom and Transnet, and why their top leadership resembles a revolving door – and most blame government interference as the main culprit.

The logistics crisis

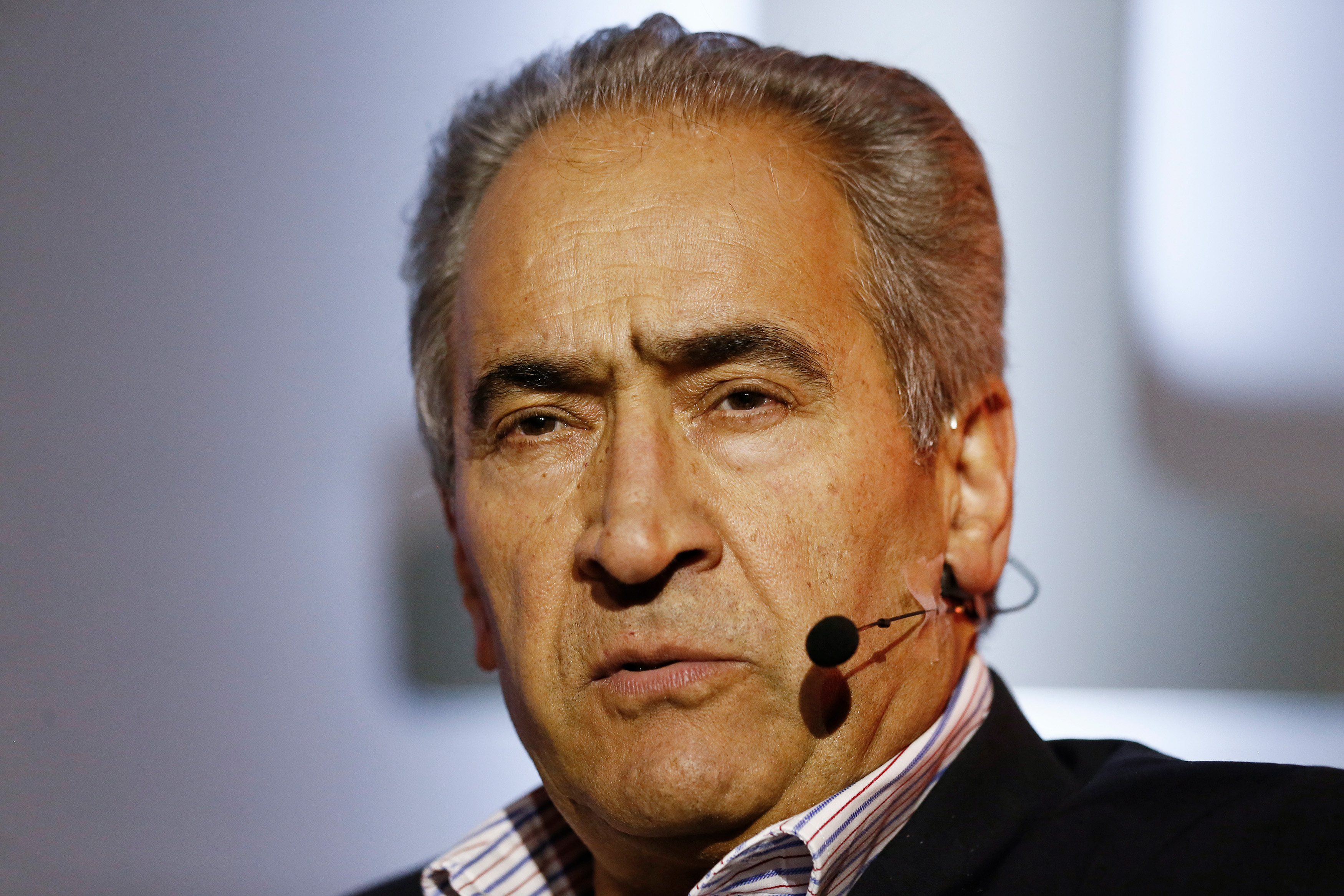

Iraj Abedian, an economist who served on the Transnet board from 2004 to 2009, lays the blame for the troubles at SOEs squarely on the government.

Since the Jacob Zuma administration, Abedian said, ministers who have led the Department of Public Enterprises, which oversees the governance of SOEs, have interfered in the operations and everyday affairs of entities such as Transnet and Eskom.

“The government does not understand the boundaries when it comes to how SOEs are run. The government not only wants to appoint the board, but also the CEO [chief executive officer], CFO [chief financial officer] and COO [chief operations officer]. You have a government that fiddles and this fiddling got worse with the Zuma years,” he said.

Abedian said, when he served on the Transnet board, Alec Erwin (the public enterprises minister at the time in Thabo Mbeki’s administration) did not interfere with the work of the board, leaving it to do its job of handling the SOE’s strategy and operations.

“Concurrence – and not approval or a final say – on decisions already made by the board would be sought from the minister. There was a clear understanding of roles and boundaries,” he said.

This arguably helped to maintain Transnet’s operational and financial sustainability. When Abedian was on the Transnet board, the SOE was profitable, recording profits of more than R4-billion every year between 2005 and 2009.

Today, losses are the norm at Transnet, and the SOE recently pencilled in a loss of almost R6-billion, mostly because of major problems with its freight rail operations.

Volumes in the rail operations have declined from a peak of more than 200 million tonnes a year in 2019 to an expected 143 million in 2023 because of Transnet’s mismanagement of the rail network, cable theft and vandalism.

Unless rail is turned around soon, South Africa stands to lose export markets, jobs and investments in its mines.

Iraj Abedian, an economist who served on the Transnet board from 2004 to 2009. (Photo: Felix Diangamandla)

Interference at Eskom

Business Leadership South Africa CEO Busisiwe Mavuso, who served on the previous Eskom board, also believes interference by the government is the main reason behind the dysfunction at the power utility.

Mavuso said seasoned and capable professionals are appointed to SOE boards, but they are usually disempowered because the government controls decision-making.

“Good governance starts with a board being able to hold the executive management to account. To do that, the board needs to have appointed – and have the right to dismiss – the chief executive officer.

“Yet, in both Eskom and Transnet, as well as all other SOEs, the CEO is appointed and dismissed by a minister, who can, under the organisations’ memorandum of incorporation, ignore the board in the process. This is the beginning of the dysfunction that besets these entities,” said Mavuso.

Business Leadership South Africa CEO Busisiwe Mavuso. (Photo: Masi Losi)

A memorandum of incorporation is a document governed by the Companies Act that outlines the roles and fiduciary duties of directors and executives.

“The minister, as the shareholder representative, should be able to select directors of the businesses in line with the Companies Act. But those directors must then be empowered and be accountable for the performance of the entities.

“Right now, that cannot happen in SOEs because the boards are disempowered on the most critical decision they should be making,” said Mavuso.

Interference by Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan is believed to be behind the sudden resignation of Eskom’s Makwana, who leaves the power utility at the end of this month. Makwana’s relationship with Gordhan broke down over the process to appoint a CEO to replace De Ruyter.

Former Eskom CEO André de Ruyter. (Photo: Brenton Geach / Gallo Images)

Eskom board chair Mpho Makwana resigned this week. (Photo: Leon Sadiki / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The Eskom board and Makwana looked far and wide (even around the world) for a CEO and interviewed close to 150 candidates since April.

The board recommended the former Eskom head of group capital, Dan Marokane, for the top position because of his management experience, technical knowledge and engineering background.

Makwana informed Gordhan about the board’s choice. However, Gordhan dithered and, four months later, he wrote to the Eskom board asking it to submit a shortlist of three candidates, stating that this was required by Eskom’s memorandum of incorporation. The effect of this is that the board and Makwana have to restart the CEO search from scratch.

In his recommendation to the board, Gordhan also said candidates over the age of 60 should be considered in the search. It is understood that the board had chosen to exclude candidates older than 60 to ensure long-term leadership stability at Eskom, where the retirement age is 65.

Makwana hit back, saying the board had concluded that Marokane was the only “appointable candidate”. The impasse had not been resolved by the time Makwana’s resignation was announced. The board is now conducting further interviews to bring the process in line with Gordhan’s requirements. Gordhan has committed himself to concluding the process by year-end.

Daily Maverick has sent a list of questions to the Department of Public Enterprises and an interview request with Gordhan. The Department of Public Enterprises has acknowledged the request and committed to respond in due course. In previous media statements, the Department of Public Enterprises indicated that the exit of executives, especially in Makwana’s case, was handled in a “positive” and “amicable” manner. The Department of Public Enterprises also maintained that the work to restructure Eskom and Transnet, and appoint new leadership, was ongoing.

An individual close to Eskom’s affairs and its board noted that Gordhan’s relationships with the executives he appoints at the power utility usually end in tatters.

“Gordhan’s track record with Eskom executives is quite poor. It’s hardly surprising because he is seen as a meddler,” said the source.

Since Gordhan was appointed to lead the Department of Public Enterprises in 2018, he has had conflicts with former Eskom CEO Phakamani Hadebe (who resigned in 2019, lasting only a year in the job); former chair Jabu Mabuza (who resigned in 2020 over Stage 6 blackouts); and De Ruyter (who served three years of his five-year contract).

Former Eskom board chair Malegapuru Makgoba has since come out to accuse Gordhan of interfering in the SOE’s operational affairs, often “undermining” the people he appoints.

At Transnet, Gordhan was viewed as providing political cover to Derby, the CEO, and Mzimela, the head of freight rail operations, despite the mining industry calling for them both to be fired for their failure to reform Transnet over the past three years.

But on 1 September, when Transnet unveiled a loss of R5.7-billion for its 2022/23 financial year, Gordhan admonished Transnet executives and the board for the SOE’s terrible performance. He ordered the board to deliver a turnaround strategy and a review of skills at the top within three weeks. This was a clear indication that Gordhan had lost confidence in Derby and Mzimela.

Siza Mzimela, Transnet head of the rail division, who leaves soon. (Photo: Russell Roberts / Gallo Images)

Transnet CEO Portia Derby has resigned. (Photo: Dwayne Senior / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Appointing credible people

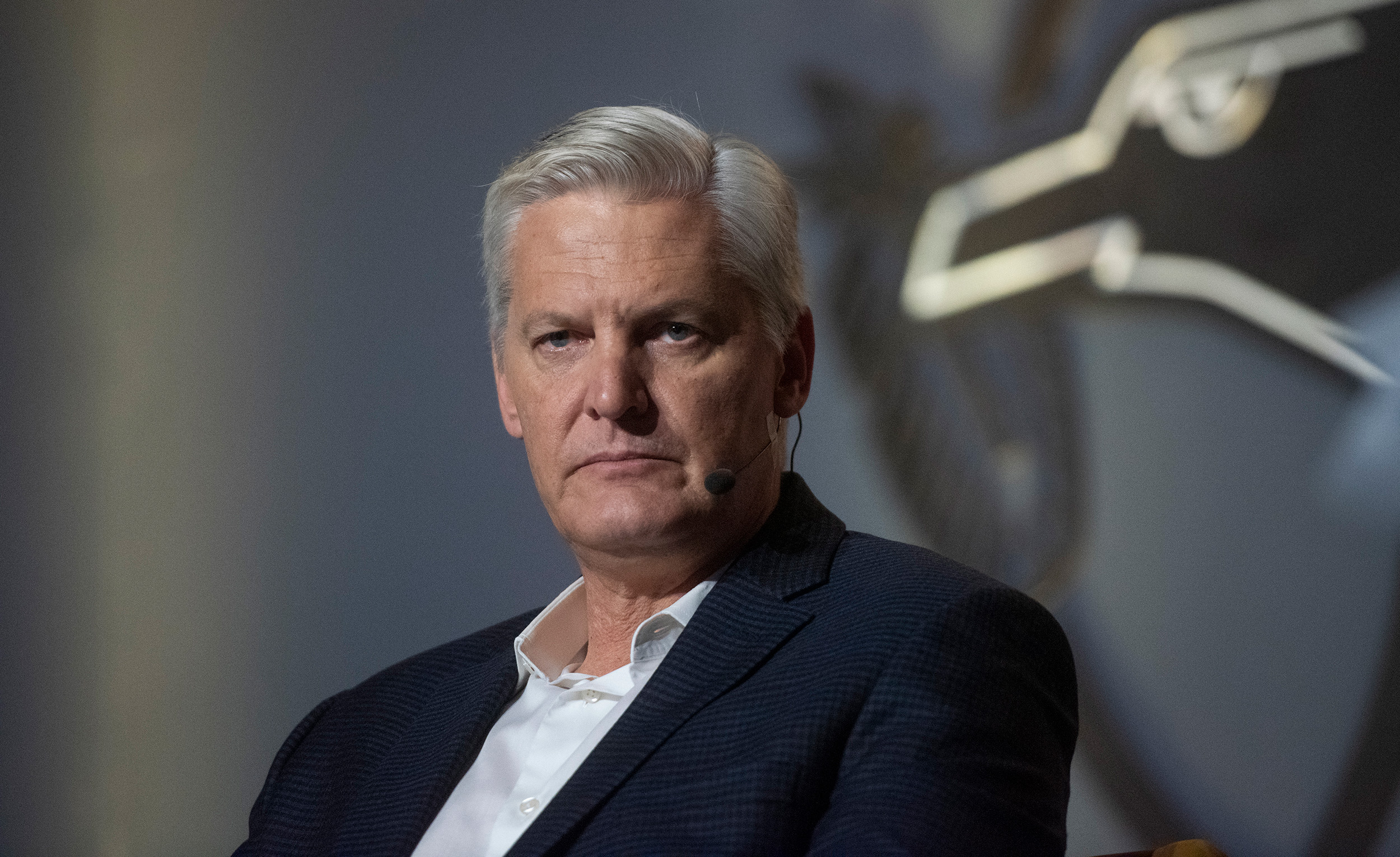

Krutham (formerly Intellidex) MD Peter Attard Montalto said finding candidates to take over from Derby or even Mzimela would be difficult because the problems at Transnet are many and entrenched.

“The board will struggle to find a credible person quickly, who must be exceptionally strong so as not to be captured by the blob layer in the company [incompetent middle managers], where the problems really lie,” he said.

Organised labour has taken an interest in the leadership changes at SOEs. The trade union federation Cosatu has called for the Transnet board and government to “move swiftly to appoint competent management” at the company.

Krutham (formerly Intellidex) MD Peter Attard Montalto. (Photo: Supplied)

Appointing capable and experienced executives is not Transnet’s strong suit. Take Mzimela, for example. She was not seen as the right person to run Transnet trains because she had no rail experience and had a dubious record as the CEO of state airlines SAA and SA Express, which were both in business rescue, with the latter now defunct. Her own airline, Fly Blue Crane, failed and is still stuck in business rescue.

Matthew Parks, the parliamentary co-ordinator for Cosatu. (Photo: Facebook)

“We need management who can turn SOEs around,” said Matthew Parks, the parliamentary co-ordinator for Cosatu. “We can’t afford the deterioration of SOEs as it poses a threat to thousands of jobs and billions of tax revenue for the state. The government needs to move swiftly to stabilise and rebuild SOEs to become enablers of economic growth.”

Political analyst Ralph Mathekga takes a dim view of the ability of the ANC to reform SOEs and return them to good governance.

“The ANC-led government has a deep philosophical problem with how it relates to the ANC because of their heavy impact on the economy and policy,” Mathekga said.

“Transnet and Eskom are not just SOEs; they are mega SOEs with a heavy footprint on policy and a heavy budget. Those are where the biggest patronage battles are fought. This is why we are seeing so much jostling for their control.”

It is possible that the state oversight of SOEs may soon see a drastic change. Gordhan may no longer be the minister after next year’s general election. The Department of Public Enterprises may be shut down under a new administration, and SOEs would then fall under the direct control of their line ministries. DM

This article has been amended to reflect the Department of Public Enterprises’ commitment to comment to Daily Maverick and reflect its position on Makwana’s exit from Eskom, and the department’s ongoing work to reform Eskom and Transnet.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link