[ad_1]

Last Tuesday was the deadline for submitting papers for next year’s Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting. I submitted one titled Completing Sidewalk Networks: Benefits and Costs, which is based on research concerning the value of non-auto mode improvements.

This study examines why and how communities can complete their sidewalk networks. Most communities have incomplete sidewalks: many streets lack sidewalks, and many sidewalks that do exist are inadequate and fail to meet universal design standards. This is unfair to people who want to walk, and increases various costs by suppressing non-auto travel and increasing motor vehicle traffic.

Recent case studies provide estimates of sidewalk expenditures and the additional investments needed to complete sidewalk networks. This indicates that typical North American communities spend $30 to $60 annually per capita on sidewalks, and would need to double or triple these spending levels to complete their networks. This is a large increase compared with current pedestrian spending but small compared with what governments and businesses spend on roads and parking facilities, and what motorists spend on their vehicles. Sidewalk funding increases are justified to satisfy ethical and legal requirements, and to achieve various economic, social and environmental goals. There are several possible ways to finance sidewalk improvements. These usually repay their costs thorough savings and benefits.

Below are study highlights.

Walking benefits

Walking (including variants such as wheelchair, scooter and handcart use) is the most basic and universal travel mode. Even astronauts walk in space and on the moon. Improving walking conditions can provide many benefits as summarized in below.

Walkability Improvement Benefits and Costs

Improved Walking Conditions |

More Walking Activity |

Reduced Automobile Travel |

More Compact Communities |

|

|

|

|

Walkability improvements can provide numerous benefits.

Sidewalks are the most basic form of walking infrastructure. Virtually everybody uses them including transit passengers when accessing stops and stations, and motorists when travelling between parked vehicles and destinations. However, unlike other transportation infrastructure, sidewalk planning often lacks basic data and funding. In most communities, sidewalk networks are developed ad hoc, built as part of new developments with no mechanism for filling in gaps, correcting mistakes or upgrading to current design standards, and there is often little enforcement of maintenance requirements. As a result, most communities have incomplete and inadequate sidewalk networks.

Sidewalk cost studies

Some recent data sources and case studies provide information on sidewalk construction costs.

- According to popular sources such as the Home Advisor and How Much, a typical concrete walkway costs $6 to $12 per square foot, with higher costs for additional prep work, thickness, design and finish. This totals $1,200 to $2,400 for a typical 5-foot walkway on a 40-foot urban frontage or $2,400 to $5,000 for an 80-foot suburban frontage. Assuming that sidewalks have a 20-year average operating life and homes have 2.5 occupants these facilities cost $24 to $100 annually per resident.

- Using detailed field data from Albuquerque, New Mexico, Corning-Padilla and Rowangould estimated that improving all sidewalks to optimum standards would cost approximately $54 million, averaging $60 per capita or about $6 annual per capita if implemented over ten years.

- A city engineering study found that approximately 40% of Denver, Colorado’s sidewalks are missing or substandard, and filling these gaps would cost between $273 million and $1.1 billion, which averages $385 to $1,550 per capita or about $40 to $150 annual per capita over a decade. The city’s new Ordinance 307 will collect special property taxes to upgrade and complete the city’s sidewalk and recreational trail network.

- Ithaca, New York charges $70 annually per household (about $30 annual per capita) and $185 per business to build and maintain city sidewalks.

- Los Angeles, California has approximately 10,750 miles of sidewalks of which 40% are rated inadequate. A 2016 class-action lawsuit by disability rights advocates requires the City to spend $1.4 billion over 30 years to fix its sidewalks, which averages about $12 annual per city resident.

- The city of Nashville’s WalknBike study estimates that new sidewalks cost $1,000 per linear foot, of which 82% is construction costs and 18% professional services. This is higher than most other estimates because it includes costs for property acquisition, curbs, stormwater infrastructure and trees.

- The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) Draft Active Transportation Plan estimates that upgrading the state transportation system to maximize active travel safety would cost $5.7 billion, which is approximately $750 per capita, or about $75 annual per capita over a decade, which represents about 13% of the WSDOT budget.

- U.S. federal and state departments of transportation typically spend $1 to $3 annually per capita on special walking and bicycling facilities.

These data sources indicate that typical U.S. communities spend $30 to $60 annually per capita on sidewalks, primarily by property owners as mandated by law, plus some government expenditures. This results in sidewalks on only 40-60% of urban streets. Completing sidewalk networks to fill in gaps and achieve universal design standards typically requires doubling or tripling these expenditures to $80 to $150 annually per capita, and more in some areas to make up for decades of underinvestment.

Comparing transportation infrastucture investments

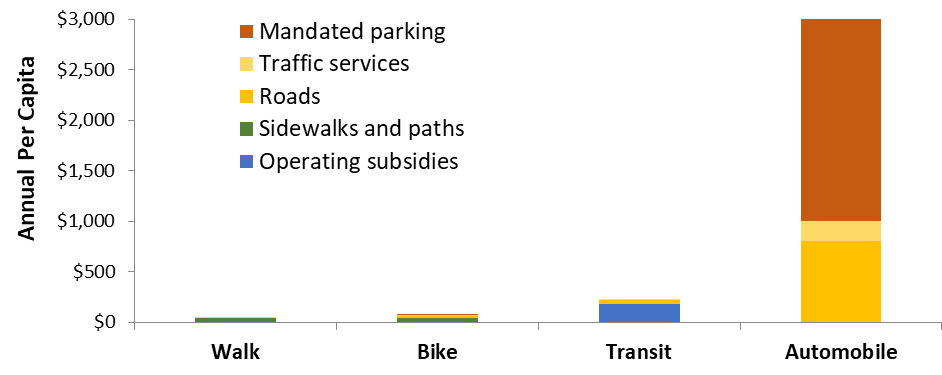

I used data from my Fair Share Transportation Planning report to compare spending on various modes. This indicates that only about 1% of total transportation infrastructure spending is devoted to sidewalks.

Figure 1 Estimated Transportation Infrastructure Spending

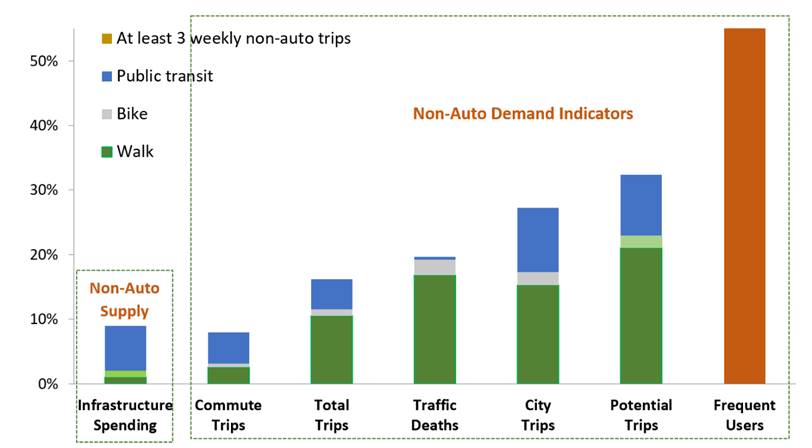

Figure 2 compares non-auto mode expenditures with indicators of their demands, including commute mode shares (which significantly undercounts walking), total trips, traffic deaths, city trips, potential trips, and frequent users. This indicates that most communities underinvest in non-auto modes relative to their demands.

Figure 2 Comparing Non-auto Infrastructure investments with Demand Indicators

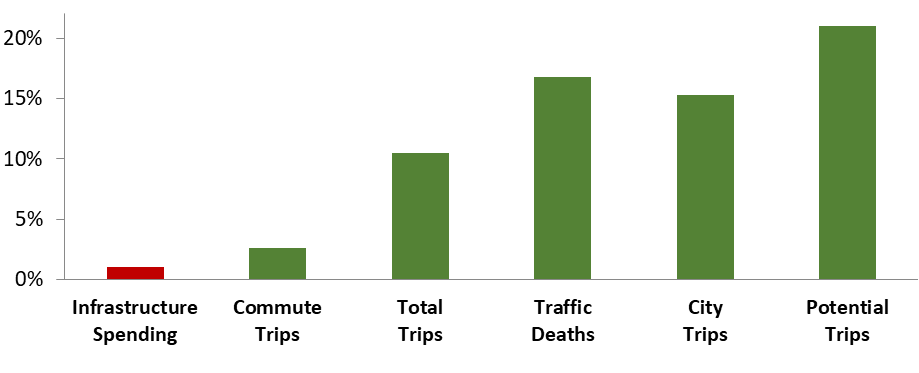

This disparity is particularly large for walking. Typical communities spend about 1% of their transportation infrastructure budgets on public walkways although walking represents 11% of total trips, 17% of traffic deaths, 15% of city trips, and an estimated 21% of potential trips if walking conditions are improved. This suggests that significant increases in sidewalk funding can be justified on social equity grounds, to ensure that pedestrians receive their fair share of public resources.

Figure 3 Comparing Walking Infrastructure investments with Demand Indicators

Travel impacts and benefits

Pedestrian improvements can significantly increase walking and reduce driving. For example, the Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program, which invested about $100 per capita in pedestrian and bicycling improvements in four typical U.S. communities increased walking trips 23% and bicycling trips 48%, reduced total vehicle-miles about 3%, and reduced active mode crash rates. Researchers Guo and Gandavarapu (2010) predict that installing sidewalks on all streets in a typical North American community would increase 0.097 average daily walk- and bike-miles per capita and reduce 1.1 vehicle-miles, about 12 miles of reduced driving for each additional active mode mile.

By improving walking conditions, serving latent walking travel demands, and reducing car traffic, completing sidewalk networks can provide large savings and benefits. Providing walkways separated from travel lanes can prevent up to 88% of crashes involving pedestrians walking along roadways, and reduces head-on, sideswipe, and fixed object crashes. Walkability improvements tend to increase nearby property values, an indication of the value residents place in walkability.

In a typical community, completing sidewalk networks is estimated to cost about $100 annually per capita. Using Guo and Gandavarapu’s estimate that completing sidewalk networks would reduce average annual vehicle miles and associated costs about 3%, this would provide about $30 in annual roadway savings, $60 in annual parking cost savings, $180 in vehicle cost savings, plus significant health benefits and reductions in traffic congestion, crash risk and pollution emissions. These are lower-bound estimates because they ignore the many ways that walkability improvements help increase urban transportation system efficiency. For example, completing sidewalk networks improves public transit access and expands the number of parking spaces that serve a destination, increasing traffic and parking system efficiency. This indicates that sidewalk network improvements provide at least a 2.7 benefit/cost ratio ($270/$100), and probably far more.

Completing sidewalk networks also helps achieve social equity goals. As previously described, most jurisdictions currently underinvest in walking facilities relative to their demands, and since physically and economically disadvantaged groups tend to rely on walking, completing sidewalk networks tends to be progressive – it helps disadvantaged groups. This is indicated by efforts by disability advocacy organizations to complete and improve sidewalk networks based on universal design standards.

Potential funding models

Many jurisdictions are developing pedestrian or active transportation plans which evaluate current walking and bicycling facilities and identify and prioritize improvements. To be fully implemented they usually require new funding options. Currently, most jurisdictions develop their sidewalk networks by requiring owners to build sidewalks when their properties are developed and repair sidewalks that fail. This approach results in incomplete and inadequate sidewalks. There are better approaches.

Options include general funds, special community-wide assessments, tax increment financing, sales taxes, and grants from other levels of government. Some jurisdictions fund pedestrian improvements as part of parks and recreation, but these are mainly special trails rather than sidewalk networks. Ithaca, New York charges household and business annual fees to build and maintain city sidewalks. Denver’s Ordinance 307, approved by referendum will collect special property taxes to upgrade and complete the city’s sidewalk and recreational trail network. In response to a lawsuit the city of Sacramento agreed to dedicate 20% of its annual transportation budget to make public sidewalks accessible. In the article, “Fixing Broken Sidewalks,” Donald Shoup recommends that cities require sidewalk repairs at the point of sale. To accelerate this process a city can offer to repair sidewalks and receive payment when the property is sold in the future. The city effectively lends funds for sidewalk repairs, with owners paying market interest rates so governments recover their costs.

Local and regional governments can also improve sidewalk data, inspection and enforcement. They can develop GIS sidewalk inventories that identify conditions and gaps, encourage residents to report problems, and hire trained inspectors – wheelchair users are particularly qualified – to collect field data.

Regional and state/provincial transportation agencies traditionally invest little in pedestrian facilities based on the assumption that active modes serve local trips and so are local responsibilities, while their mandate is to serve longer, motorized intercity travel. However, that division is a fallacy. In fact, many regional, state/provincial facilities, including urban arterials and highways, serve local trips and are affected by walkability. Sidewalk improvements can reduce traffic volumes and congestion on those facilities, directly and by improving transit access.

Conclusions

Walking is the most basic and universal travel mode, and sidewalks are the most basic walking infrastructure, but they are often overlooked and undervalued in transportation planning. Completing and improving sidewalk networks can help achieve many economic, social and environmental goals.

Recent case studies indicate that typical North American communities spend $30 to $60 annually per capita on sidewalks, and would need to double or triple these spending levels to complete their networks. This is a large increase compared with current pedestrian spending but small compared with what governments and businesses spend on roads and parking facilities, and what motorists spend on their vehicles. Sidewalk funding increases are justified to satisfy ethical and legal requirements, and to achieve various economic, social and environmental goals. There are several possible ways to finance sidewalk improvements. These usually repay their costs thorough savings and benefits.

For more information

ABW (2018), Bicycling and Walking in the U.S.: Benchmarking Report, Alliance for Biking & Walking.

Torsha Bhattacharya, Kevin Mills, and Tiffany Mulally (2019), Active Transportation Transforms America, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy.

Justin Boyar (2016), Walkability: Why it is Important to Your CRE Property Value, JLL Real Estate.

David Boyer (2018), Sidewalk Asset Management: Financial Modeling the Total Cost of Sidewalks, Dissertation, Georgia Institute of Technology.

Ralph Buehler and John Pucher (2023), “Overview of Walking Rates, Walking Safety, and Government Policies to Encourage More and Safer Walking,” Sustainability, Vo. 15(7).

Max A. Bushell, et al. (2013), Costs for Pedestrian and Bicyclist Infrastructure Improvements, Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center.

Alexis Corning-Padilla and Gregory Rowangould (2020), “Sustainable and Equitable Financing for Sidewalk Maintenance,” Cities, Vo. 107.

Bianca Gonzalez (2023), “Accessibility lawsuits are bringing slow but steady wins for disabled city residents,” Prism Reports.

Jessica Y. Guo and Sasanka Gandavarapu (2010), “An Economic Evaluation of Health-Promotive Built Environment Changes,” Preventive Medicine, Vo. 50, pp. S44-S49.

Todd Litman (2022), Evaluating Active Transport Benefits and Costs, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Todd Litman (2023), Fair Share Transportation Planning, World Conference for Transportation Research.

Minnesota Walks (2018), Sidewalk Repair Funding Guide, Statewide Health Improvement Partnership.

Donald Shoup (2022), “A Faster Path to Safer Sidewalks,” Bloomberg.

[ad_2]

Source link