[ad_1]

CHICAGO — Plans for a multimillion-dollar tent camp that would have sheltered almost 2,000 migrants a night from the bitter winter cold are now being scrapped by the state after toxic chemicals and heavy metals were found onsite.

In the meantime, outside organizations — especially churches — are pitching in to help.

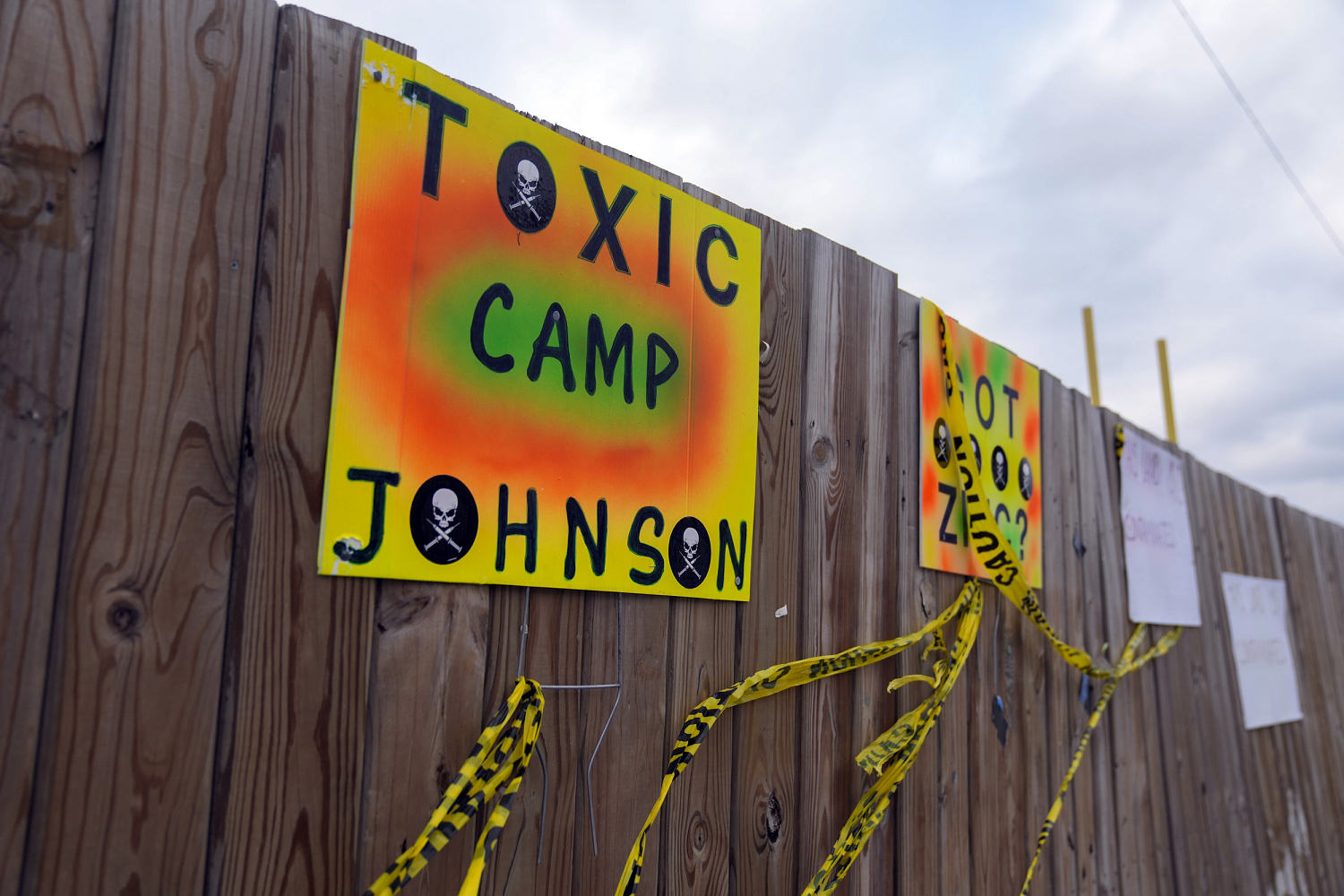

Three Chicago aldermen are now calling for the resignation of seven officials from Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration after the city insisted multiple times that the site was still safe to build on and that the most problematic levels of contamination had been removed.

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker pulled the plug on the construction of the $65 million tent camps in the Brighton Park neighborhood, near Midway Airport, after the state Environmental Protection Agency reviewed an 800-page report released by the city. The report showed that mercury, arsenic, lead, cyanide, pesticides and the now-banned cancer-causing compounds known as PCBs were found on the 9.43-acre property.

After the state announced it was permanently canceling plans for the site, Johnson said “discovering toxicity there wasn’t a surprise.” City officials have pointed out that mercury had been removed and gravel had been put on top as part of remediation efforts and that it would have been safe.

But residents of the neighborhood have been protesting since plans were first made public. After the announcement of the cancellation, locals expressed relief.

“It is toxic and now can we sit down and actually talk about what we can do that is humane — this is a concentration camp,” Brighton Park resident Richard Zupukus told NBC Chicago.

The city signed the lease in late October for $91,400 a month to use the land as is — meaning there were no guarantees about the compliance with health and safety regulations, NBC 5 investigates found.

The city and the state have been working toward a goal of getting people and families who have recently migrated to the United States into larger shelters by mid-December. Hundreds of migrants have been waiting for their spot in shelters, sleeping in police stations and at O’Hare International Airport in the interim.

The city’s plan to feed asylum-seekers through the winter also recently fell through; the state stepped in with an additional $2 million in funding, on top of the $10.5 million it had already allocated toward food bank resources.

‘We want to give them hope’

Churches are spearheading the opening of new shelters thanks to an alliance of faith-based organizations organized via what the city is calling its Unity Initiative.

“There’s more than 100 churches in the city. If we get the church involved in many areas, you know we can relieve some of the stress that the city is dealing with,” said John Zayas, pastor of Grace and Peace Church, one of the 17 churches involved in the initiative.

While the churches’ funding comes from their own networks of donors, the city helps coordinate the resources through the initiative and directs recently arrived migrants who are on the streets to the church shelters.

Grace and Peace has been providing people who have recently migrated with temporary shelter at eight locations since they first started arriving in the city over the summer. More than 400 families have cycled into permanent living situations — both in Chicago and out of state — within the city’s limited 60-day policy.

“We felt like we just didn’t want to just house them,” Zayas said, “we want to give them hope.”

The volunteers at Grace and Peace help migrants get cash jobs or start their own businesses — like a woman who now sells empanadas at an in-house cafe at the church.

“We have companies lined up to hire folks who have their work permits,” Zayas added.

At one of the temporary shelters, Emilie, who migrated from Venezuela, told NBC News that while she was warned about the Chicago winter, she’s been given coats and warm clothes through the church’s shelter. Emilie, whose last name is being withheld for security reasons, said she brought her entire family to the U.S. because they feared for their lives after an armed group killed her husband’s two brothers.

She said they entered the U.S. through El Paso, where they were put on a bus to Chicago. “The [Texas authorities] know we will have support here, so we aren’t in the streets with children. Here in Chicago, we have that support,” she said in Spanish.

Emilie hopes to become a hairstylist, which was her job back in Venezuela.

“We’re looking for work, but it’s difficult since we need the proper documents,” she said in Spanish. “And once we’re working, we can support ourselves and then help other families that are coming over.”

Santiago, 7, who is also from Venezuela, said he was excited to be learning English in school — his temporary shelter helped him enroll there — while his father just got a job as a mechanic.

Zayas wants to share the lessons they’ve learned with other churches, helping them understand logistical needs, including what to do if they don’t have the right facilities to take in people on a massive scale, and how to connect them and support other churches as more migrant families arrive each week.

“It’s not slowing down. But you know, Chicago is a city of broad shoulders, and we can handle it,” he said. “We have a lot of good folks in the city of Chicago that are looking to be helpful. And so we’re excited about the opportunity.”

[ad_2]

Source link