[ad_1]

MEXICO CITY — In a country with around 110,000 people reported as missing, presumably dead, locating them could be just a few clicks away.

That is the hope behind Angelus 2.0, a computer program developed by the Mexican government in an effort started four years ago.

While many relatives of the missing people have had to take it upon themselves to find traces or remains of their loved ones, Angelus conducts the search from an office south of Mexico City. The software is able to process thousands of documents and databases and find connections and patterns that elude the human eye.

“We are producing relevant evidence for the location of tens of thousands of disappeared people,” said historian Javier Yankelevich, a soft-spoken 34-year-old who at times got emotional during his interview with Noticias Telemundo.

“This is the type of response that is needed,” said Yankelevich, who leads a team that has been working with the Angelus program for about three years, within the country’s National Search Commission together with academics from the National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt).

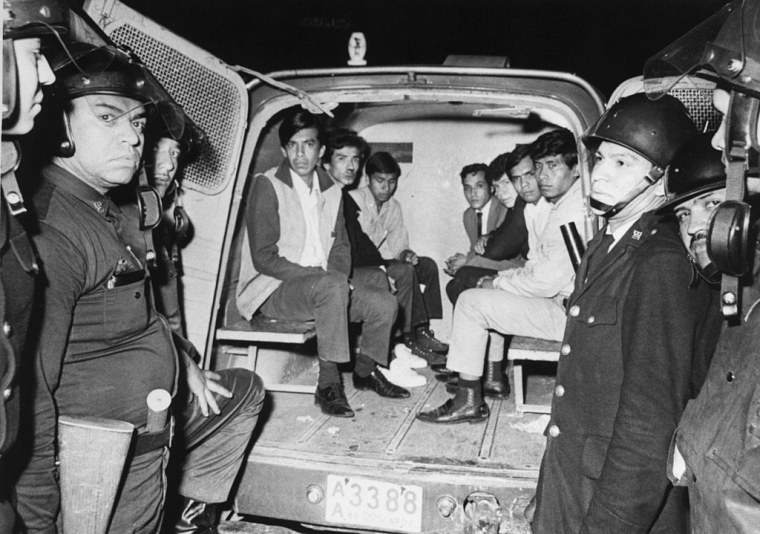

Angelus is currently focused on reviewing facts about people who were forcibly disappeared between 1964 and 1985. Authorities and groups linked to Mexico’s then-ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (known as PRI in Spanish), repressed and persecuted with systematic violence those they considered “disruptors” or insurgents.

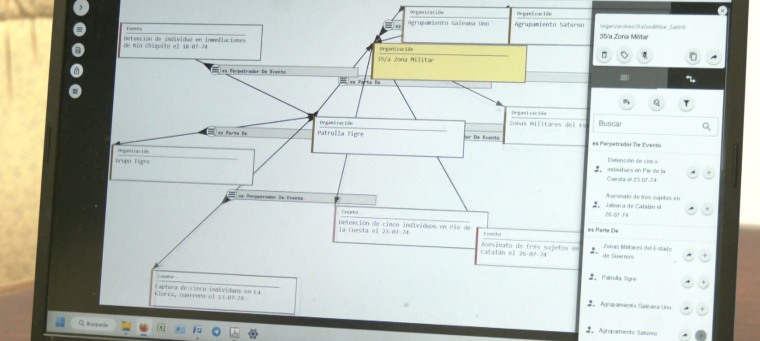

The software gathers information — where was the missing person last seen, did someone who survived government detention share a cell with someone with the same name, etc. — and makes links and provides clues as to the person’s whereabouts.

Behind the program there is a multidisciplinary team: historians, archivists, computer scientists, biologists, lawyers.

Yankelevich said they have already been contacted by a unit of a state prosecutor’s office, asking whether the program could help find information relevant to their ongoing criminal cases.

Angelus could even lay the foundation for similar tools to be used in Guatemala, Colombia and Chile — countries where regimes, dictatorships or paramilitaries also perpetrated disappearances and crimes in a massive and systematic way.

“The central question in the search for people is ‘where,'” said Yankelevich. He noted that when it comes to cases of missing persons as part of government repression, it’s never about just one person missing. “If we don’t manage to generate a methodological level that transcends one individual, we will never solve it.”

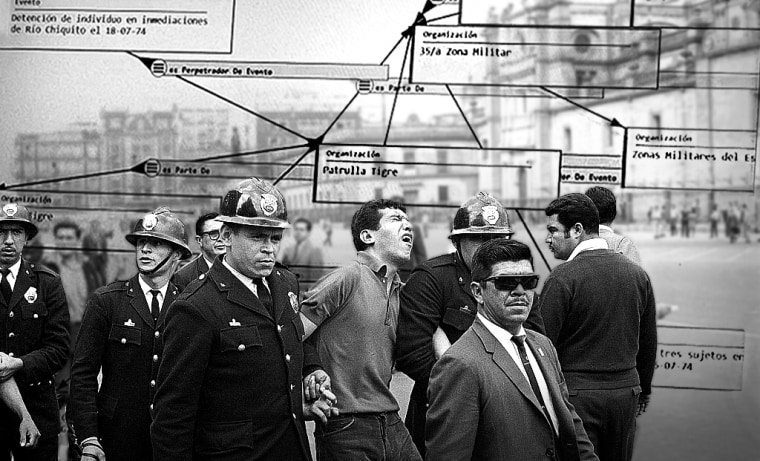

Angelus is also designed to create graphic charts that show all the connecting lines between missing persons, perpetrators and places. This allows researchers to spot relationships and coincidences, listing for example the names of people who ended up in the same clandestine site but did not seem linked otherwise.

Citing one case, Yankelevich said Angelus made possible to get enough information to contact survivors of one of the largest clandestine counterinsurgency centers, Campo Militar No. 1.

Then, last September, they were asked to visit that military site, which covers thousands of square miles and today operates as a military court venue, to see what they could recognize, such as confirming sketches and identifying specific spaces where the violence took place so that the forensic analysis could be more accurate.

Angelus’ reach is widening now that prosecutors are beginning to show interest in it to help them solve their cases, Yankelevich said, visibly frustrated for the delay. “It’s been very difficult — although I can’t understand why they wouldn’t want to” use the information. That aspect of his job is like “swimming against the current,” he said.

“To the extent that you find the victims of forced disappearance, you will find information that can be used to do justice. And to the extent that you do justice, you will find useful information to find the victims,” the historian said. To date, only one agent has been prosecuted and convicted for the disappearances during the Mexican counterinsurgency.

The impact of technology

It is not the first time technology has been used to address the issue of missing people in Mexico.

In recent years, for example, the nongovernmental organization Data Cívica group compiled a database with the locations of clandestine graves and another one matching file numbers of recent disappearances with a person’s identity, giving a name to a numbered file.

In other countries, technological programs have also been used to solve cases. In the United States, for example, there are hackers who study information from open sources to help authorities, especially in cases of missing children. They look to see if someone with features like the missing person can be seen in the background of a photo someone shared on Instagram with geolocation. Agencies like the FBI have forensic data — fingerprints or facial identification.

Worldwide, the Forensic Anthropology group uses social media posts and videos to reconstruct events. One of the group’s investigations, done in collaboration with Mexican NGOs, looked into the disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in September 2014.

In South America, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team —which has spent four decades searching for the people who disappeared during the dictatorship — has begun incorporating drones and laser technology to scan land and water for possible debris.

Yet the fact that Angelus is a government enterprise, specifically created to search people, sets it apart. It gives more institutional visibility to the search for the truth — what happened, who committed the crime, where the victim ended up — and, with it, a greater opportunity for families and survivors to access justice. It seems less likely tax authorities, for example, would ignore proof and evidence of someone’s life or disappearance when it’s being collected by other branches of government.

“These people have been missing for more years than I have been in the world and we are not the first to try [to elucidate the whereabouts],” Yankelevich said. “However, we are the first, a new generation, to put technological tools of this kind at the service of this mission. When the number of individual cases overwhelms the number of, say, available detectives by such magnitude, these other means become crucial.”

Knowing history so as not to repeat it

Hundreds of boxes with thousands of documents each sit today in the Mexico’s General Archive, partially declassified, describing the actions of authorities during the so-called counterinsurgency.

These documents, Yankelevich said, show how the perpetrators —largely the General Directorate of Political and Social Investigations, and the Federal Security Directorate, agencies that spied on and detained those they considered to be dissidents — used to repeat their methods.

“The same vehicles, weapons and places of clandestine detention” were used against “the same type of victims, victimized for the same reasons,” Yankelevich said. Those who were forcibly disappeared were mostly young people, students and teachers (some gathered in groups and associations) who protested and called for greater transparency and a stronger democracy.

This systematic nature of the forced disappearances implies, according to the researcher, that “the cases cannot be seen individually because the destinations are not individual.” Several people were probably tortured at one point by the same officer using the same nickname while in the same location, for example. Hence, an Angelus is key to better elucidate these patterns.

Feeding Angelus is hard work; it has involved devising the development of algorithms and doing machine learning so that the program can detect and match repeated names, even when one of them, for example, is lacking an accent. It’s also crucial to reconcile the different disciplines and units making up the team, and to be able to appeal to authorities and prosecutors and have them join the technological effort to use Angelus as evidence in their criminal proceedings.

But on top of that, the work behind Angelus involves people devoting themselves almost daily to reading documents and records written by agents detailing atrocities: how they tortured, beat, raped and disappeared and what tools — or in particularly bloody cases, live animals — they used to commit violence.

Keep doing battle

The work has a real impact for victims and their families, particularly when they can get answers. But beyond that, Yankelevich said, the continued effort reinforces the notion that this type of violence is unacceptable and inadmissible, regardless of what motivated the actions of the agents.

“You feel that you are part of a movement toward a slightly more civilized society,” the historian said.

Since Angelus was made from scratch and there is no intellectual property component, the group is planning to make public a version of the program’s code later this year.

“We are legally in the possibility and of course in the desire that whoever this serves can use it,” said Yankelevich. The hope is that it’s used beyond Mexico too, and that people adjust it to their needs.

Perhaps in this way, Angelus will be able to grow and improve, until it reaches a version where it not only puts together information on Mexico’s earlier counterinsurgency and its forced disappearances, but also on those missing at the hands of current criminal groups that systematically abuse the inhabitants of towns disputed by Mexican cartels or migrants in transit from Central and South America.

In this way, Angelus will honor its name’s inspiration: a painting by Paul Klee that shows the “angel of history,” a creature that knows that in order to build the future, one also needs to look at the past.

An earlier version of this story was originally published in Noticias Telemundo.

[ad_2]

Source link