[ad_1]

“I don’t know how any of us can think any of this is replicable without me,” says Giorgio Armani, speaking in a small backstage meeting room a few hours before his “One Night Only Venice” catwalk show, held last weekend at the Arsenale di Venezia, an ancient complex of shipyards dating back to the 12th century.

Armani, whose show dovetailed with this year’s subdued Venice Film Festival, has been determined to do things differently from many of his Italian contemporaries. While Valentino, Gucci and Versace have all been sold to foreign investors, he remains the sole shareholder of the business that bears his name, a decision some analysts say has undervalued the group.

But the 89-year-old designer and chief executive says he has never doubted his choices, and is especially keen to avoid a takeover by one of the French luxury conglomerates. “These French groups want to do everything, I don’t get it . . . it’s a bit ridiculous,” he says. “Why should I be dominated by one of these mega structures that lack personality?”

Although he told American Vogue in 2021 he was open to a “liaison with an important Italian company” — quickly kindling speculation the company was for sale — he says now that he’s not going anywhere: “Everyone tells me I should just retire and enjoy the fruits of what I’ve built, but I say no . . . absolutely not.”

When Armani attended the film festival in Venice for the first time around the late 1970s, he says he felt like an “intruder”, a lesser-known character among a firmament of stars.

“Photographers pictured me with some actor friends and I thought I didn’t deserve it, I knew I had to work hard to deserve it and eventually I did,” Armani recalls.

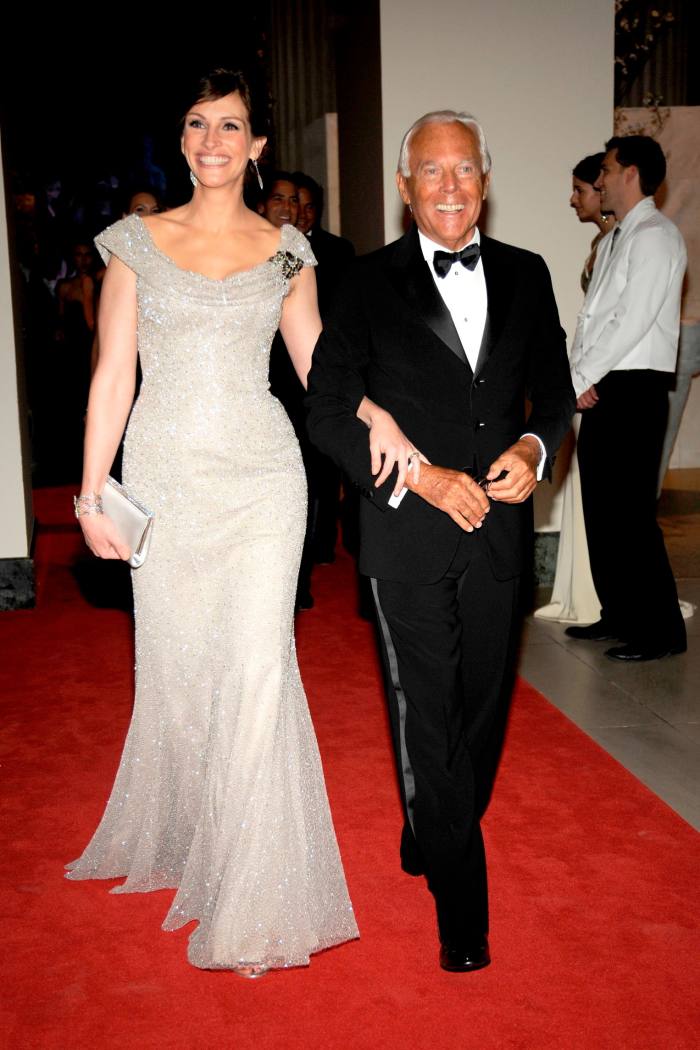

The show, a revamped version of the harlequin-inspired spring/summer 2023 haute couture collection he showed in Paris in January, underlined how far he’s come. Actors Sophia Loren, Jessica Chastain and Benicio Del Toro were there in spite of the SAG-AFTRA strike that has kept many in Hollywood away. They joined fashion personalities including Santo Versace and Remo Ruffini of Moncler in a five-minute-long standing ovation at the end.

To many of those present, including some of Armani’s senior staff, the two-day event resembled something of a farewell.

Earlier that day, the designer — known for his rigour and formality — had taken a press conference by surprise as he strayed from the details of the show to describe how it was the general public who appreciate him as a person and not the stars that make his efforts worthwhile.

“The other day I [took] a picture with an old lady, who must have been 85 and was probably never able to afford any of my designs in her life, and she cried. It was hard to hold back the tears,” he said, teary once again.

Armani began working in fashion in 1957 after dropping out of medical school. He took a job on the design team as a window dresser at the Milanese luxury department store La Rinascente, going on to design for Nino Cerruti’s Hitman men’s collection before founding his own fashion house in 1975 alongside the late architect Sergio Galeotti. His deconstructed take on men’s jackets was the antithesis of the typical Savile Row structured suits. His breakthrough came five years later when he dressed Richard Gere in the film American Gigolo.

Fashion historians consider Armani, a favourite of Hollywood stars spanning multiple generations, the most influential figure of the 20th century in Italian high fashion alongside the late Gianni Versace and Valentino Garavani.

The group, which includes brands Emporio Armani and Armani Exchange as well as the higher-end Giorgio Armani line, posted €2.35bn in revenues in 2022, up 16.5 per cent on the previous year. Armani is Italy’s second-richest man, after the heir to the Nutella empire Giovanni Ferrero, and his business now also includes restaurants, luxury hotels and a beauty license with L’Oréal.

Armani has been laying plans for the company’s future — admitting, candidly, that he is “afraid to die”.

“I know Giorgio Armani, the company, is identified with me, so it is my responsibility to make sure this will continue and that the company will have a footprint that will resemble il signor Armani,” he says.

In 2016 Armani set up the Giorgio Armani Foundation, designed to fund social projects and shield his group from a future takeover or breakup — a set-up similar to that of Swiss watchmaker Rolex. As part of his succession plan, the foundation will own an undisclosed stake in his fashion empire, with the rest going to his family. Nieces Roberta and Silvana Armani work for the group, while Andrea Camerana, his nephew, is a board member.

Pantaleo Dell’Orco, who heads the men’s style office and has worked with Armani for 46 years, is also taking on an increasingly important role within the company. He sits on the foundation’s board and is also poised to inherit a stake in the company. At a men’s show in 2021, Dell’Orco joined the designer for the customary end-of-show bow, a suggestion that he may one day succeed Armani as menswear designer. Silvana Armani, meanwhile, works with her uncle on the women’s collection.

Armani’s designs have evolved over the decades. The Venetian catwalk shimmered with black headpieces and ruffled harlequin-like collars, sequinned lozenge-patterned dresses, tops and trousers in a variety of unconventional colours.

Armani says he’s changed over time and he has accepted the evolution of fashion, but only to a certain extent. “At one point I knew I could either [stick to] my own style, or [give up as] I would have never adapted to the new trends.”

“Change is happening and I have also changed . . . the thing is that today’s designers draw inspiration from the past and it’s not like they are inventing anything unless they do a mattana,” a colloquial Italian expression to describe an erratic behaviour.

What bothers Armani, though, is what he defines as a lack of loyalty by the younger generation of fashion consumers. “It’s very hard nowadays, because what young people like today, they won’t like tomorrow . . . and this underworld of [VIPs] set trends, there’s a lack of culture, of substance . . . everything is very, very superficial,” he says.

Armani remains closely involved in the day-to-day of running the business. His aides claim there isn’t a single document Armani doesn’t personally sign off nor a single figure he doesn’t look at in running the company.

“Detail is essential . . . it is often the minutia that makes the difference, not the great idea as those are rare,” he says.

The night before the show he welcomed his guests, including a small group of journalists, on his yacht for a drinks reception. When they headed off to dinner, also hosted by Armani, he took a water taxi to the show venue instead. He wanted to make sure the lights on the runway were perfect.

Sign up for Fashion Matters, the FT’s weekly newsletter on the business of style

[ad_2]

Source link