[ad_1]

A new generation of asset management chief executives have called time on a “golden decade” for their industry, warning that it is becoming increasingly difficult to navigate the competing pressures of markets, regulators and politicians.

“The complexity of the demands on an asset manager are clearly increasing,” said Ali Dibadj, chief executive of Janus Henderson. “Clients are asking more of all of us, regulators are asking more from all of us, and our clients’ clients are asking more from us.”

Katie Koch, chief executive of Los Angeles-based TCW Group, said asset managers were “facing increasing complexity around evolving regulation, migration of investment opportunities from public to private markets, globalisation of the opportunity set and the more recent politically charged portfolio management environment”.

After a decade of zero rates and quantitative easing that pushed equity markets to record highs, investors are grappling with the challenge of a regime change towards both higher inflation and higher interest rates.

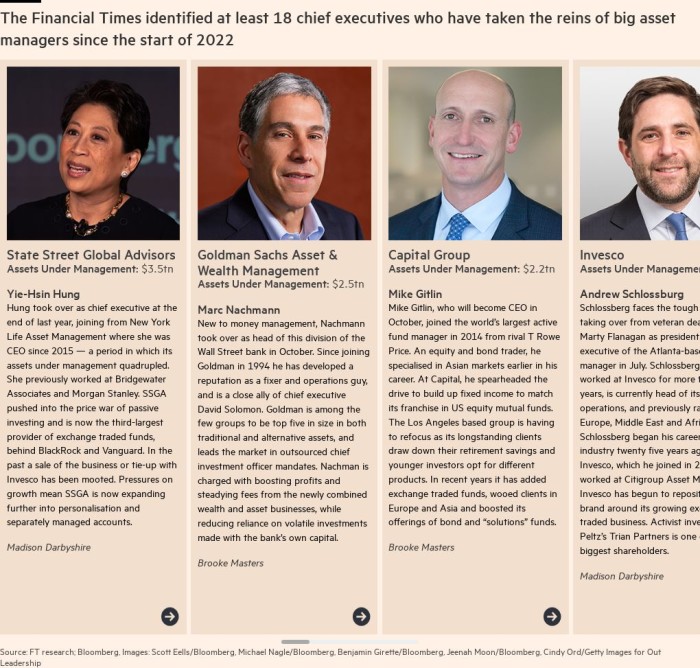

“Asset management used to be a rising tide that would lift all boats and that’s no longer true,” said Yie-Hsin Hung, chief executive of State Street Global Advisors.

The Financial Times identified at least 18 chief executives who have taken the reins of big asset managers since the start of 2022. This new guard is charged with stabilising their businesses following the worst year for the roughly $60tn industry since the financial crisis.

Big falls across markets combined with investor outflows and spiralling costs, compounding pressure on active asset managers that have been fighting the march of passive investing.

Investors globally pulled $530bn from investment funds (excluding short-term money market funds) last year, the fund industry’s worst for new business since 2008, according to data provider Morningstar.

Investment managers’ revenues are underpinned by the fees they charge on assets under management, and falling assets are putting cost-to-income ratios — a key measure of investment manager profitability — under pressure, especially for less efficient players.

“The golden decade for asset management is over,” said Stefan Hoops, chief executive of DWS, adding that investors now faced a market environment where “not everything is going up and up and up” but “costs are”.

Last week BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, warned that the “traditional investing approach” of 60 per cent stocks and 40 per cent fixed income will serve investors poorly over the long term, calling time on a strategy that has been a cornerstone of many asset managers for more than 30 years.

“The complexity of the markets right now — not just equities and bonds, but consumer behaviour, economics, geopolitics and regulation — is creating a lot of volatility and uncertainty,” said Andrew Schlossberg, chief executive of Invesco. “That makes creating a long-term business strategy challenging and we think it’s going to be with us for a while.”

Asset managers have responded to profitability pressures by trying to diversify their businesses, adding higher-margin products such as private assets or targeting new client types or geographic regions, sometimes through acquisitions. Their business models have become increasingly elaborate and difficult to manage as a result.

“The challenges of complexity are greater than the challenges of scale,” said Rob Sharps, chief executive of T Rowe Price. Customers now come to T Rowe through multiple channels, including direct access on brokerage platforms, through advisers or to buy specific products such as alternatives. “Then we do that around the globe.”

He added: “It becomes a complicated business especially with the proliferation of regulation and different client preferences for vehicles, strategies or structures in end markets.”

Increasingly fragmented and complex regulation is another area of concern, particularly around the fast-growing sector of investing on the basis of environment, social and governance factors. Asset managers are trying to balance the demands of a highly interconnected investment industry against retreats from globalisation and the increasingly politicised nature of ESG in the US.

“Regulation is becoming much more complicated,” said Matthew Beesley, chief executive of Jupiter. “Regulatory pressures have increased in every region. We are also seeing regulatory divergences emerging within Europe following the UK’s exit from the EU.”

For example, European regulators took a lead on defining standards for ESG investing, with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, which aims to improve transparency and prevent greenwashing. But the UK is consulting on its own version of rules, which could take a different approach to the EU in the aftermath of Brexit, and the US Securities and Exchange Commission is preparing rules around ESG disclosures.

Karin van Baardwijk, chief executive of Dutch asset manager Robeco, said that with the growing demand and associated supply of ESG products, “the risk of greenwashing is becoming more prevalent. This can damage the credibility of our industry as a whole . . . and will ultimately lead to more regulation.”

In the US, asset managers including BlackRock and Vanguard are finding themselves a lightning rod for both sides of the political spectrum. Republican politicians are attacking them over the use of ESG metrics, contending that they are hostile to fossil fuel investments, while Democrats have criticised them for failing to do more to fight climate change.

Meanwhile, asset managers are locked in a war for talent, notably in areas such as private assets, technology and sustainable investing, and trying to keep investing in their businesses to stay ahead of the competition.

“The pressure on cost, inflation of wages, and the war on talent is really here to stay,” said Naïm Abou-Jaoudé, chief executive of NY Life Investment Management.

“And the pressures we have on regulation, compliance and all the requirements mean the business is becoming more demanding . . . all of this is costing a lot in terms of investment to be really efficient as an organisation.”

The chief executives all agreed that investors today face a future quite different from those of their predecessors in recent decades.

To navigate this more complex environment asset managers will “need to work harder and be even more innovative . . . operating across traditional silos,” according to Marc Nachmann, global head of asset and wealth management at Goldman Sachs.

“More extensive relationships and resources — globally distributed and amplified by better technology — will be increasingly needed for idea generation, deal sourcing, portfolio construction, and value creation,” he said. “These are not small investments to make.”

[ad_2]

Source link