[ad_1]

When it comes to queer books, the loudest headlines may be about bans and censorship, but a quieter truth about the state of LGBTQ books reveals the resilience of their authors and commitment of their readers. The queer titles debuting in 2023 are as full of joy as they are examples of resistance, and those in the industry say LGBTQ writers are only getting more ambitious.

“We’re moving into a lot more queer joy but not shying away from the difficulties of what it means to be queer,” said Natalie Edwards, a literary agent at Trellis Literary Management. “There’s a lot more perspectives across the spectrum that we’re hearing from.”

Whether queerness is core to the story or woven into the narrative, Edwards said there was once “this sense that queerness had to be palatable and safe” to achieve widespread success, but writers are pushing the boundaries and readers are responding. Sales have boomed.

In 2021, LGBTQ fiction sales surged in the U.S., reaching nearly 5 million units, doubling the prior year’s sales, according to a report released in June by market research firm The NPD Group. And while queer young adult books are often the target of book-banning efforts, these titles drove the highest gains in the category, the report found.

With the book market expected to grow overall in 2023, according to market research firm Grand View Research, queer bibliophiles are predicting an even greater diversity of queer stories for readers to choose from this year.

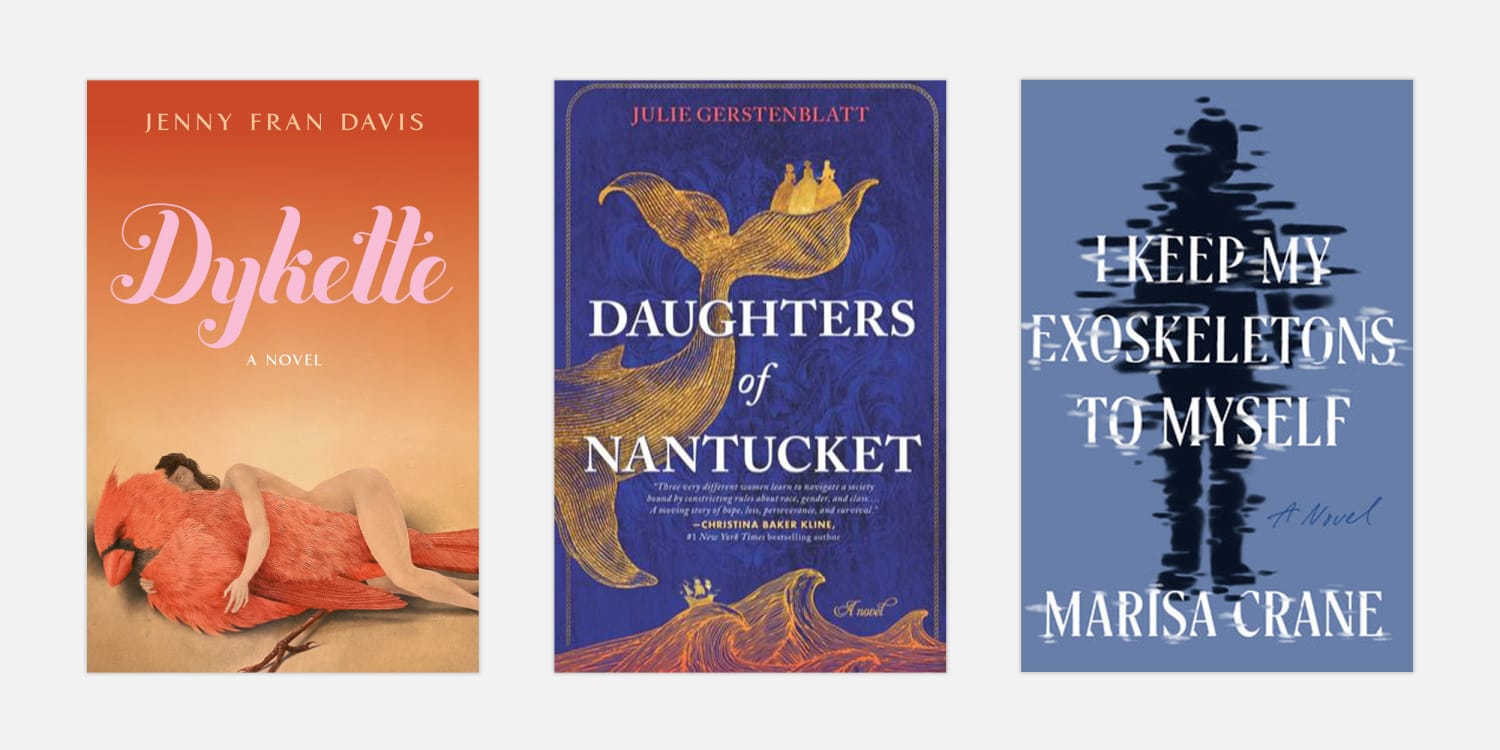

On Tuesday, Marisa Crane’s speculative novel, “I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself,” published by Catapult, hits shelves. Centered on a queer mother raising her daughter in a surveillance state, this story — which pits a community of defiant misfits against a corrupt government — has been described as “Dept. of Speculation” meets “Black Mirror.” Crane’s debut novel has been named in most-anticipated-books lists by Goodreads, Independent Book Review and Lambda Literary, among others.

In March, the novel “Daughters of Nantucket” will be released by Mira, a HarperCollins imprint. This historical fiction title, represented by Edwards’ literary agency, weaves a queer narrative into the story of three women living on the tiny Massachusetts island of Nantucket in 1846. The story encompasses the whaling industry, astronomy and a massive fire that causes the characters to make some life-altering decisions.

Then in May, the highly anticipated book “Dykette” by Jenny Fran Davis debuts. Published by Henry Holt and Co. and mentioned by Edwards as a title she’s looking forward to reading, this debut novel traces a woman’s 10-day trip with her partner and two other queer couples. It’s a story promising “a complex web of infatuation and jealousy” and “a spiral of destructive rage.” Davis’ debut novel has been named in most-anticipated-books lists by BuzzFeed, Literary Hub and Electric Literature, among others.

Dan Smetanka, editorial director of Catapult Book Group, said he has an editorial staff across three imprints — Catapult, Counterpoint Press and Soft Skull Press — devoted to finding and supporting LGBTQ voices.

“The rubrics are the same for any writer or new project: Who is the writer, what are they saying, how are they saying it and what does this add?” he said. Smetanka, a book industry veteran, said the queer books he is seeing today have “an ambition now that is appropriate for the times we live in.”

Like many publishers, Smetanka sees book bans and censorship efforts as a call to action against something that “has no place in our society.”

“I hope writers see it and want to immediately address it, and publishers feel a renewed vigor and passion to push back and publish more into that space,” he said.

Two other queer titles debuting this year from Catapult are Amelia Possanza’s “Lesbian Love Story,” which combines memoir with real-life love stories of women across several generations, and Ruth Madievsky’s “All-Night Pharmacy,” described as a Rachel Kushner-meets-David-Lynch “fever dream of an LA novel about a young woman who commits a drunken act of violence just before her sister vanishes without a trace.”

Trans and nonbinary writers in particular have seen their books be as censored as they have been celebrated. The most challenged book in 2021, according to a report released in April by the American Library Association, was “Gender Queer,” an illustrated memoir by nonbinary author Maia Kobabe. The ALA’s Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2021, its most recent list, also includes nonbinary author George M. Johnson’s memoir “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” which came in at No. 3, and Susan Kuklin’s “Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out,” which was No. 10.

For some trans publishers, these censorship efforts have meant a consideration of what the future looks like for books written by trans and nonbinary authors and how community-based publishing can support them.

“You never know how the political situation will go, how backlash will go. When does the money dry up? What happens if our books don’t sell or the books we want to write don’t sell?” said Casey Plett, co-founder and publisher of the feminist press LittlePuss Press.

Plett and her co-founder, Cat Fitzpatrick, take a different view than many other publishers and are generally more involved in the writing process than what is standard for the industry. They work in the tradition of queer zines and small presses, where books gain traction within the community and visibility by word-of-mouth.

“We feel dedicated to running our own show, and that’s important,” Plett said.

LittlePuss is working on two short story collections, one by Anton Solomonik and another by Emily Zhou, both trans writers.

“I do think that from the perspective we have as trans editors, we felt we were the right people to take these books on and bring them into the world,” Plett said.

She couldn’t promise these books would be ready this year (“One of the nice things about being an indie is you have some flexibility,” she said), but she did share the 2023 queer titles she’s most excited about reading: Alison Rumfitt’s “Tell Me I’m Worthless,” a queer horror title published by Tor Nightfire, an imprint of Macmillan, that will be released in the U.S. on Tuesday; Hazel Jane Plante’s “Any Other City,” a two-sided fictional memoir debuting in April from Arsenal Pulp Press with an A side that tells one story and a B side that tells a related story; and a story collection by writer Alice Stoehr that will be self-published this fall.

When it comes to considering a queer future, and what’s next for queer books, that’s something that’s been on the mind of Suzi F. Garcia, the editor of Lambda Literary, a nonprofit that advocates for LGBTQ books and authors.

She said she sees writers looking “to balance telling important stories with the question of, ‘What does a queer future look like?’ And that includes love and joy, and can those two things coexist?”

Garcia said there’s a variety of work finding different ways to answer that question, and she pointed to “Black on Black,” a collection of essays on racial tension by novelist and scholar Daniel Black. She described the book as having a “queer core” and a sense of hope while discussing issues critical to LGBTQ and Black communities.

Garcia said she reads a significant amount of queer poetry, which “can have a lot of themes of trauma and joy,” and she shared three poetry titles she’s looking forward to: “Have You Been Long Enough at Table,” a debut poetry collection by Leslie Sainz, the daughter of Cuban exiles, which is being released in September by Tin House; “Beautiful Machine Woman Language” by Catherine Chen, a collection that has “a lovely delicateness to it that kind of cuts” (published by Noemi Press, where Garcia serves as co-publisher); and “Saltwater Demands a Psalm” by Kweku Abimbola, a collection of poems that “groove, remix, and recenter African language and spiritual practice to rejoice in liberation’s struggles and triumphs,” according to Graywolf Press, which will release the collection in April.

Garcia said that in 2023, we are still considering how the pandemic has informed our lives and how we re-enter the world both as individuals and as a community. These themes, she said, are playing an outsize role in upcoming titles.

“Finding safety in community, joy and love in community, is a large part of how we get through the trauma and pain that comes with being a marginalized community,” Garcia said. “We are all finding different ways.”

[ad_2]

Source link