[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Markets took one look at the consumer price index yesterday and went right back to bed. The Vix and Move volatility indices are back near recent lows. Yawn. Wake us up with a bracing email: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

CPI: just barely bad enough

August’s CPI report wasn’t horrible. True, it came in a bit on the hot side, with core inflation at 0.3 per cent. But the most important trends — disinflating rents and goods — stayed true.

But there was a glimmer of the inflation risks that still linger. Start with non-housing core services, the Fed’s inflation bugbear. After four months of encouraging deceleration, it crept up in August, rising 0.4 per cent (dark blue line below):

The main culprit was transportation services, particularly the temperamental airfares category. Transportation services, which make up 7 per cent of core CPI, rose a full 2 percentage points in August owing to a 5 per cent increase in airfares. Blame Opec. Production cuts have helped push the oil price above $90 a barrel, from under $70 in June. Airfares are highly sensitive to the cost of jet fuel, and transportation is more broadly exposed to energy.

The oil price increase, which has lost momentum, could fade. But a sustained high oil price poses an inflation risk through two channels. One is inflation expectations. Headline inflation, which is what people experience, rose 0.6 per cent in August. Petrol prices are plastered everywhere and play an outsized role in people’s idea of the price level. Long-run inflation expectations, it should be noted, are already near the higher end of their historical range.

The second is direct pass-through to core inflation. Over a 3-month horizon, a 10 per cent supply-driven oil price shock raises core inflation by just 3-5 basis points, Morgan Stanley economists estimate in a note out yesterday. But a longer lasting price rise “could bleed over into core inflation as price contracts reset and to the extent companies have pricing power to pass higher prices on to consumers”, they write.

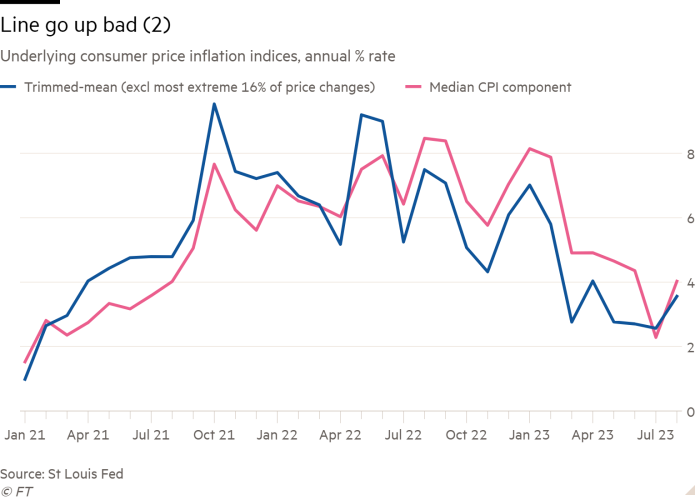

Another risk is inflation breadth. This is not just about transportation or energy. Omair Sharif of Inflation Insights notes that several unexpected categories ticked up, including household furnishings and medical care. Measures of underlying inflation also rose after yesterday’s data:

This gets at a broader idea: for all that can be learned slicing and dicing the data, a top-down approach must be considered, too. This cycle has been inscrutable but the plain fact is that spending is strong right now. Until proven otherwise, we have to assume that economic resilience matters to inflation, that high levels of corporate profits and wage growth don’t match a tidy return to 2 per cent. We are still holding our breath on inflation. (Ethan Wu)

The big bad basis trade

Since the great financial crisis, people tend to worry when a lot of leverage builds up in any financial market, the way it did in the market for housing finance prior to 2008. Everyone knows that particular mess won’t reoccur, but they are sniffing around for an analogous mess, so they can avoid it, profit from it, or (in the case of people like me) look clever by noticing the problem before it explodes and then write a book about it.

Lately, people are looking with trepidation (or is it anticipation?) at the Treasuries basis trade. The Treasury market makes a good target for anxiety. It nearly failed in 2020, when volatility jumped, liquidity disappeared, and the Fed had to intervene. One culprit in that might have been speculators who had leveraged exposure to Treasuries that they had to jettison in a hurry.

The basis trade is one form this speculation takes. It works like this. I sell a bunch of futures contracts; that is, I agree to buy a lot of Treasuries at a certain price, for the sake of simplicity let’s call it $100.50, at some point in the future. Let’s call it three months. Now I buy a bunch of Treasuries for $100 (why are the futures more expensive than the cash Treasuries? Mostly because there is lots of demand for futures for use in hedging interest rates). At the end of the three months, I close the futures trade, providing my $100 Treasury in return for $100.50. I have made 50 cents. Yay. What is nice about this trade is that it is matched. I mostly don’t care what happens to the price of Treasuries or Treasury futures over the life of the trade. All I have to do is hold the Treasury and then deliver it as specified in the contract.

The problem is that 50 cents is not a sexy return on a trade that ties up $100 for three months. It’s not as good as simply buying a Treasury bill. But because the trade is matched — it’s almost a pure arbitrage — I can borrow tons of money to set it up. All the more because it is based on Treasuries, the risk-free asset. Roughly speaking, I can borrow $98 to buy that $100 in Treasuries, using the Treasuries as collateral. Leveraged up 50x, the return starts to look good, even when the cost of all the leverage is subtracted.

But the leverage makes the trade risky, as an excellent 2020 report from the Office of Financial Research explains. The first issue is that the trades are usually funded in the overnight “repo” market, and if rates move and this financing becomes more expensive, it can wipe out the profits from the trade, and then some, forcing me to close the trade in a hurry. What is more, if the prices of Treasuries or Treasury futures move, I have to post additional margin with my lender or the futures clearinghouse. As long as they move in the same direction, I’m mostly fine, because when one requires more margin, the other will require less. If they move in different directions, however, I have to get out as fast as I can.

When either risk bites, I’m selling my Treasuries in a big hurry. If a lot of traders are doing this at the same time, the selling may overwhelm buyers, resulting in panic in the world’s most important securities market and the disappearance of liquidity — a March 2020 type of situation.

The reason is everyone (the Fed, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal) is focused on the basis trade just at present is because there is suddenly a lot of Treasury futures selling going on the market, more even than in the run-up to the 2020 car crash. A chart of the exposure from Ian Harnett and David Bowers of Absolute Strategy Research:

One response to the build-up of leverage in the Treasury market is to wonder why the hell the speculators didn’t learn their lesson the first time. But of course they did learn their lesson: the lesson is that if things get really bad in the Treasury market, the Fed will intervene. The only surprising thing about the return of high leverage levels is that it took as long as four years.

This gets at the heart of the problem, which is that if leveraged speculators cause a problem in the Treasury market, innocent bystanders will get hurt. People like banks and insurance companies, for example, depend on the Treasury market for liquidity management, and every price signal in the world goes haywire when yields jump. So the best possible outcome — that the speculators and their investors get crushed and prudence re-enters the market — has unacceptable side effects. Regulation, including capital requirements for Treasury market participants, becomes appealing to people like Gary Gensler at the SEC.

But the problem with regulating leverage in one place is that it tends to pop in another. There really is no discipline like market discipline. Part of the solution has to be accepting that perfect liquidity in the Treasury market is a fantasy, and everyone, from banks to hedge funds, must deleverage their business models accordingly. The alternative is skipping from one crisis to the next.

One good read

“President Xi’s cabinet line-up is now resembling Agatha Christie’s novel And Then There Were None . . . Who’s going to win this unemployment race? China’s youth or Xi’s cabinet?”

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

[ad_2]

Source link