[ad_1]

Businessweek

LORD OF THE DEEP

For years a shipwreck hunter has battled governments and rivals over the ocean floor’s riches. He’s kept his identity a secret, until now.

By Kit Chellel, Olivia Solon and Jonathan Browning

Illustration by Ricardo Rey

Officers from the Icelandic coast guard watched the ship on the control room monitors—a solitary dot on the blue expanse of the nautical map. The dot had been circling 120 miles offshore for several days in April 2017, in weather no sane sailor would loiter in. Near-gale-force winds howled across mountainous seas; rain mixed with sleet.

By the look of the ship, it wasn’t there to catch fish. Taking on supplies in Reykjavik a few days earlier, the Seabed Constructor’s unusual appearance had attracted local news crews and a visit from a coast guard commodore. Its sleek orange hull supported a space-age communications array and a helipad. A gigantic crane shaped like a scorpion’s tail arched from its stern. Now, as the Constructor bobbed in the storm, the coast guard radioed the vessel’s bridge to ask its business. The response—“research”—was so infuriatingly vague that officers dispatched a helicopter to investigate. The pilot buzzed overhead and reported seeing equipment being winched in and out of the waves.

The Constructor was outside Iceland’s territorial waters but inside its zone of economic influence, just a few miles from an undersea internet cable. Senior coast guard personnel debated what to do, then sent an armed patrol boat to escort the Constructor to port.

The Seabed Constructor, viewed from an Icelandic coast guard vessel. Source: The Icelandic Coast Guard

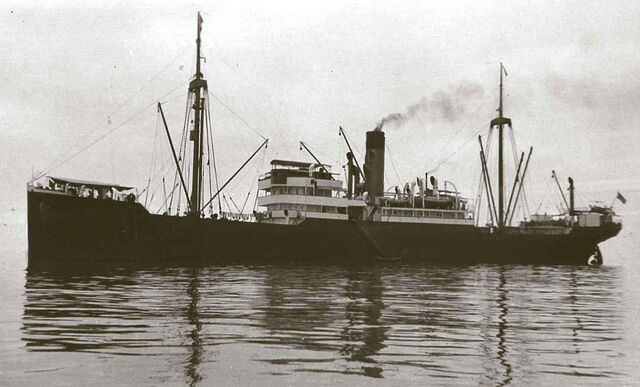

When the ship got back to Reykjavik, the captain and two operations managers were taken to a police station to be interviewed by Icelandic detectives. All three were cooperative but cagey. They were contractors working for a London client whom they couldn’t, or wouldn’t, identify. They said they’d been hired to search for valuables on the SS Minden, a German cargo ship sunk during World War II that lay broken some 2,240 meters (7,350 feet) below the surface.

The Minden was in Brazil when war broke out in 1939. Historical records don’t show what the vessel was carrying back to Nazi Germany, but they indicate that a handful of German businessmen were on board, including two bankers. Whatever the cargo, it was valuable enough that, when the Minden was spotted by the British navy, the captain scuttled the ship rather than let it fall into enemy hands.

SS Minden, a German cargo ship sunk near Iceland in 1939. Source: Wrecksite

At first the Icelandic coast guard was reluctant to allow the operation to continue, but it relented a couple of weeks on after receiving a letter from the Constructor’s lawyers threatening to sue. To recover whatever the Minden contained, all the salvors needed to do was return with an environmental permit. The application set out a plan to use battery-powered, remotely operated subs to cut open the hull, bend back a sheet of metal and retrieve a wooden box from the mailroom. “Our client expects that the operation will take approximately 24 to 48 hours if weather conditions are favourable,” the document said.

At no point did the Icelandic authorities learn the identity of this mysterious client, the backer of the Minden expedition. They couldn’t have known that the German ship was one of dozens he’s pursued over the years. Media reports about wrecks this man has found or recovered have described him variously as an anonymous London financier, “the unknown salvor” and “the Originator.” He’s marshaled a high-tech operation to recover the lost treasures of history, spanning centuries and entire civilizations and covering most of the blue portion of the planet. And he’s managed to keep this remarkable enterprise secret—until now.

To piece it all together, Bloomberg Businessweek investigated the financier’s operations across 11 months, interviewing more than 40 current and former employees of his companies, as well as contractors, archaeologists, government officials, law enforcement officers and attorneys. Many of them requested anonymity, concerned about possible legal consequences from discussing what the financier considers his private business. The research also drew on corporate and legal filings, government records and satellite ship location data to confirm previously unreported expeditions.

The glitter of deep-sea treasure has lured adventurers since time immemorial, and most have ended up poorer instead of richer. There are about 3 million wrecks in the ocean, an unharvested bounty worth untold billions of dollars, but getting to them can be dangerous, difficult and ruinously expensive. Recently, though, advances in underwater technology have opened up swaths of the ocean floor to exploration. Beyond gems and cultural treasures are rare minerals, oil, gas, battery metals and creatures unknown to science—all outside the reach of any state regulator that might constrain an eager entrepreneur. In the deep-sea gold rush that’s resulted, what matters most is getting there first.

Right now, the only ones with the resources to join in are corporate interests and wealthy individuals whose goals may or may not be aligned with the rest of humanity. The Originator is the most prolific of them all—the most successful shipwreck hunter in modern times, perhaps in all of history. His name is Anthony Clake, and he’s a 43-year-old hedge fund executive who rarely leaves dry land.

Clake’s pursuit can be traced back to another quest popular with the super rich: the hunt for lower taxes. At the turn of the century, enterprising accountants and bankers in the City of London were creating ever more ingenious shelters for their clients’ money—investing in Harry Potter film distribution, say, or arranging for bonuses to be paid in fine wine.

The contribution London investment firm Robert Fraser Asset Management made to the genre was tax-efficient shipwreck hunting. The idea was to mitigate the high risk of losing millions of dollars on a fruitless search by claiming a juicy tax break in the event of failure. To do this, Robert Fraser created companies tailored to individual wreck operations, then used leverage and other accounting tricks to supercharge investors’ tax relief.

A Robert Fraser brochure touting its approach hails a new era of wreck recovery, aided by million-dollar marine robots and side-scan sonar that creates accurate 3D seafloor maps. Among the firm’s first investors were celebrities and tech entrepreneurs, as well as executives at the London hedge fund Marshall Wace. Founded in 1997 by Paul Marshall and Ian Wace, it grew to become one of the top hedge funds in London, then the planet. Today it has $62 billion under management and a reputation for making money in good times and in bad. Both of the founders put money into Robert Fraser’s marine ventures, and so did Clake, a talented young Marshall Wace executive.

The Financial Times reported in a story about the hedge fund that, in 2002, fresh from his studies at the University of Oxford, Clake developed a successful portfolio system that reviewed stock recommendations from 1,000 or so analysts to generate trading ideas. Those who’ve worked with him say his passion lay there—with technology and data. But he took a particular interest in shipwrecks, according to several people interviewed for this article who asked not to be identified, citing nondisclosure agreements. (A Marshall Wace spokesman says the investments were made in a personal capacity, unconnected to the hedge fund’s business.)

By 2015, Robert Fraser had formed a partnership with a leading deep-sea recovery company, Odyssey Marine Exploration Inc. The financial firm’s marine unit had attracted about 100 individual investors, sponsoring expeditions around the world, each with its own code name and off-the-shelf company. One of the most ambitious, the “Enigma” project, sought an historic wreck called the Napried, known to be stuffed with priceless relics when it sank somewhere off the coast of Lebanon in 1872.

The vessel was carrying cargo for Luigi Palma di Cesnola, an American consul in Cyprus who had a taste for Mediterranean antiquities. Back then he was considered a collector, though today what he did would likely make him a plunderer. Cesnola shipped some 30,000 pieces of sculpture, weaponry and pre-Biblical kitchenware to the US, where they can still be seen in a New York Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition bearing his name. He lost about 5,000 more pieces on the Napried.

Marshall, Wace and Clake all invested in the Enigma project, and Clake was enthusiastically involved in details such as the potential location of the wreck, says Colin Emson, Robert Fraser’s executive chairman at the time. The expedition didn’t find the Napried, but it did stumble across several trading ships dating to the last days of the Ottoman Empire, one so large that archaeologists christened it “the Colossus.” Inside were turquoise-glazed jars full of peppercorns, Ming dynasty Chinese pottery and Turkish tobacco pipes.

The Enigma team sent a tethered remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) to reach the Colossus. Using suction cups mounted on robotic arms, the ROV painstakingly removed several hundred items. The whole operation cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, at a minimum. Although the value of the cargo was mainly historical, the intention, for Robert Fraser and its clients at least, was always to sell some of it to private collectors and make a profit. “You don’t need too many Ming vases to make that worthwhile,” Emson says.

They never got the chance, because when the expedition ship went to Cyprus to refuel in December 2015, the authorities detained it and seized all the Colossus relics. The Cypriot government is sensitive about cultural heritage, a legacy of Cesnola’s activities. The authorities released the ship but kept the cargo on the island, where it’s remained under lock and key ever since.

At Robert Fraser, Emson liked to say there were three key questions about any given shipwreck: Can you find it? Can you fund it? Can you keep it? The last of those often poses the biggest challenge. It’s not just Cypriot officials who are hostile to treasure hunters. Seventy-three countries have ratified the United Nations’ 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, which states that signatories will take “all appropriate measures” to prevent the commercial exploitation of shipwrecks. And academics feel so strongly about the sanctity of sunken ships that they argue divers and their machines shouldn’t even touch a wreck site. “You don’t go to the Louvre and stick your finger on the Mona Lisa,” Robert Ballard, the marine geologist who discovered the Titanic, said after trophy hunters ransacked the world’s most famous ship.

On the other side are pro-salvage archaeologists who argue that historical material left in the deep is of no use to anyone. Better to haul it up and put at least a portion on display. One member of this faction, who asked not to be named discussing sensitive matters, says those in the “don’t touch” school are akin to religious fanatics, calling them “the Archaeo-Taliban.”

Technically there’s nothing to stop salvage crews from recovering anything they want from the seafloor. But even sunken treasure once belonged to someone, and salvors are effectively obligated to at least try to find the legal owners. That can lead to competing claims and years of litigation. The Colossus was carrying vases made in China 500 years ago, which had been acquired by Turkish traders for the palace of a long-dead sultan somewhere in the Ottoman Empire. Who might own that cargo today? Enigma tried hiring lawyers in Cyprus, who argued that the ship had been found in international waters, where the country had no jurisdiction, but the effort got jammed up in the island’s judicial bureaucracy. (A spokesman for Enigma says that the Colossus excavation was a “purely scientific venture” with new funders and that Clake is no longer involved. Clake’s spokesman says his stake by the latter stages of the project was less than 5%.)

Before the matter could be resolved, the Robert Fraser era of wreck exploration ended. British tax inspectors cracking down on aggressive tax-avoidance schemes began reviewing and rejecting the deductions claimed by the firm’s investors. Without the tax breaks, treasure hunting lost a key part of its appeal. Emson says the deals were “totally lawful, totally legal and commercial”; the British tax agency declined to comment.

By that point the Marshall Wace executives, and Clake in particular, were already frustrated with Robert Fraser, according to several people familiar with the situation. In meetings, Clake sometimes gave the impression he thought he could get better results without them. Behind the scenes, he was already trying.

About a decade ago, several companies with vaguely nautical names were registered in the UK. Their ownership wasn’t always evident. Advanced Marine Services Ltd. listed its main shareholder as an Isle of Man trust. Other entities recorded Clake or Marshall as investors, or they employed directors with close business ties to Marshall Wace. The companies were created specifically to recover and sell valuable cargo from shipwrecks. Clake was the driving force behind them, according to numerous sources interviewed by Businessweek.

In 2015-16 he ordered a half-dozen autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) from a Norwegian manufacturer. These free-swimming robots resemble bright orange torpedoes and can descend as far as 6,000 meters, without the risk of a disaster like the one that befell the Titan submersible, which imploded while diving to view the Titanic, killing all five passengers. Each would normally cost several million dollars, but Clake got a bargain because the offshore energy industry was in a slump and wasn’t buying as many as usual, according to two people familiar with the deals.

Ocean Infinity’s autonomous underwater vehicles. Courtesy: Ocean Infinity

Clake’s innovation was to put all the AUVs on one ship and deploy them in formation like a bomber squadron, carpeting vast areas of seabed with sonar. Multiple AUVs could search more ground and get better-quality scans while reducing time spent at sea and the costs of fuel and labor. Clake and the other investors in his companies also acquired businesses in Louisiana and Texas whose employees had experience operating the robots for the oil and gas industry.

His employees and contractors describe him as a demanding boss who seemed to have access to almost unlimited funds. Marshall Wace had in 2015 sold a 25% stake in the business to Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., the Wall Street private equity titan, for about $150 million in shares and an undisclosed amount of cash. (Clake netted under $50 million.) Clake’s earnings aren’t disclosed publicly, but Bloomberg News reported in 2018 that he’d been Marshall Wace’s top earner in the year through that February, receiving compensation of about £61 million ($75 million). Given that Clake and his partners clearly didn’t need the extra income from treasure hunting, they seemed to be in it primarily for the challenge. He never showed an interest in going to sea.

In deciding where to start searching, Clake drew in part on records from Lloyd’s of London, the shipping world’s economic engine since the 18th century. His researchers discovered the insurance market was digitizing its records, including manifests, ship designs, letters and safety certificates—a compelling dataset, from a hedge fund analyst’s perspective.

It wasn’t long before his AUV squadron started finding targets, or “hard returns” in radar operator’s jargon. In 2016 they dove to the site of the SS Coloradan, an American steamer that was sunk by a German U-boat 250 miles off Cape Town during World War II, killing six crewmen. The wreck contained drums of gold precipitate that a Clake expedition later recovered. (His spokesman says Clake wasn’t a shareholder in the company that claimed the gold cargo. His boss Paul Marshall was, however, along with another Marshall Wace executive and several of Clake’s regular collaborators, company records show.)

That same year, off the coast of West Africa, according to two sources familiar with the operation, Clake found the SS Benmohr, a Scottish-owned cargo ship that held 50 tons of silver coins from the Bombay Mint. It took 12 hours to lower containers 4,500 meters, have robots load them with silver and winch them back up. The coins were later melted down and sold. Neither discovery was made public, and everyone involved had to sign an NDA pledging secrecy. (Clake’s spokesman says he had a 25% stake in the proceeds from the Benmohr salvage.)

Turning treasure into money—the “can you keep it?” part of Emson’s equation—remained a challenge. But Clake and his partners found a way to streamline that process, too. Anything they found was reported to the UK Receiver of Wreck, an obscure British government post created to find the true owners of lost cargo from around the world and ensure salvors were rewarded fairly. If the owners emerged, Clake-affiliated companies could claim compensation of as much as 80% of the cargo’s value. If no one came forward after a year, they could legally keep anything found outside British territory.

To make matters more confusing for anyone trying to keep track, Clake’s crews sometimes moved material from a wreck to another location on the seafloor for later collection, a practice called “wet storage.” Such methods helped Clake keep his prospecting private from governments that might’ve seized the treasure, and from rivals who might’ve been tracking his ships via satellite. But the tactics weren’t without risk. On one occasion a salvage expert who felt he’d been unfairly treated returned to a wet storage site without Clake’s knowledge and helped himself to several tons of silver coins, according to several sources with firsthand knowledge of the incident. Clake’s team was told the salvor had taken them to South Africa and smelted them into cups to disguise their origin.

Clake himself wasn’t above some sleight of hand in pursuit of shiny objects. In 2017, after negotiating a salvage contract with the UK, his former partners at Odyssey Marine Exploration sent subs 2,500 meters into the North Atlantic darkness to recover 526 bars of silver from the SS Mantola, a World War I cargo carrier it had discovered previously. The subs reached the wreck to find the silver … gone. In between discovery and recovery, someone else had gotten there, and Odyssey’s lawyers thought they knew who. They filed a lawsuit in New York claiming possession of the wreck and asked the judge to order a deposition from the person they held responsible: “Odyssey has credible information that Mr. Clake was the individual who directed the removal of the silver bars from the Mantola.” The lawsuit didn’t go anywhere, in part because the Receiver of Wreck refused to release information to Odyssey’s lawyers.

Documents obtained by Businessweek through a freedom of information request show Odyssey’s suspicions were right, though. Clake’s contractors had taken the silver and claimed an award through the Receiver of Wreck: all perfectly legal and handled without publicity.

No find of Clake’s brought more potential for riches—and more complications—than one of his first: a Spanish galleon discovered off the Colombian coast in 2015. The San José, sunk by British warships three centuries ago, has been the fever dream of treasure hunters ever since. It was known to contain gold, silver, pearls and jewels plundered from the New World, valued at anywhere from $1 billion to $17 billion.

In December 2015, then-Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos announced that the San José had finally been located by the Colombian navy with help from “international experts.” He didn’t identify them, though he did say they’d used an undersea robot. The ship, Santos said, would be salvaged for a “great museum” that the country would build. Even as more details emerged about the search, the identity of the individual who’d financed and planned it remained unknown, with Clake referred to in Colombia only as the Originator.

Screen captures from footage of the San José wreck site. Source: YouTube

The Colombian government had awarded the contract for the search to Maritime Archaeology Consultants Switzerland AG, or MAC, a Clake-linked, Swiss-registered company that had received funds from a charitable trust in the Netherlands previously used by Clake. Under a recently amended Colombian law, MAC might be entitled to as much as half the proceeds from any recovery.

But profiting from wreck hunting is never so simple. Almost immediately after the San José’s discovery was announced, the Spanish government claimed the ship for Spain. A rival US treasure-hunting company also emerged to claim that MAC had stolen its coordinates. And the Indigenous Qhara Qhara people of Bolivia, whose ancestors had mined the precious metals on board, publicly declared their interest.

The presence of London-based millionaires in a dispute about colonial pillage was awkward, to say the least. In 2018 the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee, a UK nonprofit dedicated to protecting marine heritage, held a private meeting for members to voice concerns about the plans to recover the San José. There, a representative from a Clake-linked company told members the excavation and museum could be partly funded by selling a limited number of artifacts, according to minutes seen by Businessweek. When someone argued that this risked breaching international treaties opposing the commercial exploitation of historic wrecks, Ian Panter, an archaeologist working with Clake, replied that not all the items on board were culturally significant enough to put on display. “What do you want to do with a million coins?” he asked.

Not long after, with disputes proliferating and the press clamoring for transparency, the Colombian government announced that it was suspending its plans to salvage the San José and build a museum. The treasure remains unrecovered, its location a state secret.

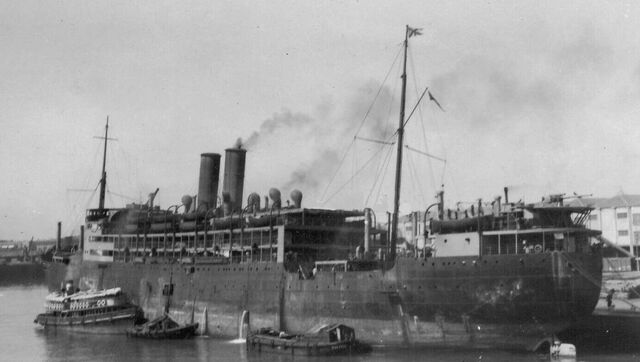

During those years, Clake was behind another controversial project—one that, because the wreck was more recent, stirred up some strong emotions. In 2017 he’d sent a salvage operation to recover precious metal from the SS Tilawa, a passenger steamer destroyed by Japanese torpedoes in 1942. Some 281 of the more than 900 people on board had died, most of them Indian—an event that’s been called India’s Titanic.

The Tilawa had been found off the Seychelles a few years earlier, in an expedition backed primarily by Paul Marshall, Clake’s boss at Marshall Wace. It had been carrying 2,364 bars of silver worth roughly $40 million. Clake’s contractors recovered the metal and set sail for Europe, taking the precaution, before stopping in Oman to change crew, of leaving the bars on the seafloor, in wet storage. No need to risk another mishap like the one involving the Colossus in Cyprus.

SS Tilawa, an Indian cargo ship sunk in 1942. Source: Wrecksite

After Clake’s company reported the silver to the UK Receiver of Wreck, the Receiver’s team determined that the legal owner of the cargo was the Republic of South Africa. The South African government, furious that it hadn’t been consulted beforehand, refused to pay a salvage award, leading Clake’s company to sue. The lawsuit is still working its way through the legal system, with a hearing scheduled at Britain’s Supreme Court for the end of November. Until the case is resolved, the silver is locked in a secure warehouse in the UK.

No one has previously connected the lawsuit to one of London’s most successful hedge funds, and the families of the Tilawa victims didn’t know about the recovery of the ship until it made the news. They’re in contact with representatives of Clake’s company but still don’t know what its operation found, having been refused access to photos or videos of what’s essentially a mass grave. (Clake’s spokesman declined to comment on the Tilawa, citing ongoing legal proceedings.)

“Hundreds of families around the world are anxious to see what is left of Tilawa and learn more of the incident,” says Emile Solanki, whose great-grandfather was lost in the attack. One person familiar with the matter told Businessweek that Clake’s subs recorded footage showing lifeboats still attached to the Tilawa, indicating that some passengers never had a chance to escape. Knowing that such evidence exists is deeply painful, Solanki says. “I yearn for the time when more will be shared.”

Clake’s various attempts to tap into the deep’s resources have in recent years converged on a single company called Ocean Infinity Group Ltd. It was registered in 2017 in the Cayman Islands, which in addition to having no corporate taxes doesn’t require owners to publicly disclose their identities. But filings from a UK affiliate reveal that Clake has at least a 25% stake. Ocean Infinity’s first chief executive officer, Oliver Plunkett, seemed light on maritime experience, having spent the previous two years working as a hedge fund tax specialist.

Ocean Infinity was public-facing, showcasing the technological innovations Clake had pioneered as well as renting out gear and finding wrecks for clients. The government of Argentina was an early one, paying $7.5 million for finding a lost submarine. The company also continued hunting treasure for its creator, as furtively as ever. Crews would find out where in the world they were being deployed only the day before leaving and had to sign NDAs, several contractors say. Even their families weren’t supposed to be aware of their final destination. (Ocean Infinity said in a statement that it takes its contractual duties of confidentiality to clients “very seriously.”)

One of Ocean Infinity’s first big jobs was returning to the site of the SS Minden, this time with the environmental permit from Icelandic authorities. In November 2017 a vessel contracted to the company sailed into the North Atlantic and launched a remotely operated sub under cover of darkness. By then journalists had worked out that anonymous treasure hunters from London were trying to salvage what the Daily Mail called “a Nazi gold ship,” though an Icelandic historian, Illugi Jokulsson, told a local newspaper there was no evidence the Minden was carrying anything particularly valuable. “Either the British company has found some new information which has eluded everyone for the past 80 years, or they are using the Minden as cover for something else,” he said.

Clake’s vessels descended to the Minden three times, with ROVs cutting away portions of the hull and removing debris to get into the bridge, crew areas and mailroom, supervised by the Icelandic coast guard. According to reports filed later with the country’s authorities, “no items of value were found.”

Three people familiar with the operation, however, say that one item was removed from the wreck and that it was noteworthy enough to be presented to an Ocean Infinity executive at port later: a wooden box. The sources either don’t know or won’t say exactly what was inside, if anything. An Ocean Infinity contractor who didn’t work on the Minden project says his team often retrieved personal belongings while salvaging a wreck, and the more intriguing objects were kept by company representatives. (“To the extent that items from any client project are handed to an Ocean Infinity representative it is to ensure they are conveyed to the relevant authority on behalf of the client,” the company said in a statement.)

Ocean Infinity became best known for its work trying to locate wreckage from Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which disappeared somewhere over the Indian Ocean in 2014 with 239 passengers on board. Clake offered the company’s services at a 2017 meeting it convened in London with various governments, aircraft agencies and accident investigators, volunteering a search vessel and its AUV squadron on a no-win, no-fee basis. Despite a 19‑week search in 2018, covering nearly as much ground in a few months as the other survey crews had in two years, the company didn’t find MH370, so it never qualified for the $70 million reward that was on offer.

“Whilst clearly the outcome so far is extremely disappointing, as a company, we are truly proud of what we have achieved both in terms of the quality of data we’ve produced and the speed with which we covered such a vast area,” Plunkett said at the time. According to a person familiar with the project, the scans did reveal several undiscovered shipwrecks—something Plunkett didn’t mention.

In 2019, Ocean Infinity brought Clake’s treasure hunting full circle, sending a ship to the Mediterranean to resume the search for Cesnola’s Napried and its collection of priceless relics. It didn’t take long for Cypriot authorities to spot the vessel and detain it at Larnaca Port. Police arrested the captain and an Ocean Infinity employee, charging them with not having the necessary permits to carry out a survey. Ocean Infinity’s London lawyer was called in, and after a few days the pair pleaded guilty, paid a fine and were released. The arrests seem to have ended Clake’s search for the Napried.

In an emailed response to questions from Businessweek, the Cyprus Department of Antiquities said it considers privately funded treasure-hunting operations to be illegal and unethical, risking the loss of historical material through destruction or sale on the black market. “Wealthy individuals conducting underwater explorations for antiquities are motivated by personal gain rather than an interest in academic matters or cultural preservation,” the email read. It’s essential, the reply continued, “to prioritise the preservation and study of cultural heritage for the benefit of future generations over personal profit.”

Whether Clake had been pursuing profit, knowledge or both, he wasn’t saying, not publicly anyway. Whatever the case, his pursuit only accelerated from there, branching out into ambitions that went far beyond silver coins. Starting in 2020, Ocean Infinity set out on a buying spree, with orders for 23 remote-controlled, full-size vessels from shipbuilders in Italy and Norway. The “Armada,” as Ocean Infinity calls it, stands to be the world’s biggest private fleet of robotic vessels, serving the oil and gas industry, cable companies and deep-sea miners. The ships will have skeleton crews initially, but the plan is to dispense with sailors altogether and steer the vessels from onshore hubs. “The impact and the scale of this robotic fleet will spark the biggest transformation the maritime industry has seen since sail gave way to steam,” Plunkett said in a press release announcing the purchase. The company also won government grants from the UK and Norway to develop eco-friendly ship propulsion technology, totaling about $17 million. (Ocean Infinity says it was part of a consortium of companies benefiting from the grants and had to match state funds with its own.)

In 2021, Ocean Infinity added a Swedish marine data group, a Portuguese subsea software specialist, an offshore wind farm tech provider and a British security firm to its list of acquisitions. It also moved into a refitted warehouse on England’s southern coast. The facility looks more like a tech campus than a shipyard. Access to the control room is by iris scan. Inside, pilots of remote submarines sit in big gaming-style chairs in front of multiple screens. The workspaces were designed by an e-sports company, and the pilots can even use Xbox-style controllers if they wish.

The UK headquarters of Ocean Infinity. Courtesy: Upperlook/Mildren Construction

Ocean Infinity’s recent clients include a wind farm project off Long Island, where it’s surveying for unexploded military ordnance. Plunkett also announced last year that the company wanted to mount a new search for MH370. And Clake’s long-ago investment in the San José could yet pay off, too: Colombia’s minister of culture told Bloomberg News this November that President Gustavo Petro wants the wreck recovered by 2026. If that happens, MAC, the Clake-affiliated company that discovered the site, has a potential claim to a finder’s fee, even as it would have to navigate a legal and political minefield to enforce it. Clake’s spokesman says that the contents of the wreck are classified as Colombian National Heritage, meaning no one is entitled to any of it, and that MAC would work on recovery for a service fee to be agreed upon with the Colombian government.

Last year, Clake sponsored an Ocean Infinity-led project to find the HMS Endurance, lost beneath the Antarctic ice for more than a century after being abandoned by the British explorer Ernest Shackleton. Clake used a charitable trust for the purpose, which helped keep his name out of the ensuing media coverage. (His primary role in the project was highlighted to Businessweek by several people and confirmed by corporate and charity records.) For three weeks, helicopters, autonomous undersea vehicles and an electromagnetic sounding system carried out a search and recovery operation, until finally the Endurance emerged from the blackness, perfectly preserved by the frigid water. It was a landmark moment in the history of marine archaeology.

HMS Endurance: sank in 1915, discovered in 2022. Source: The Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust/National Geographic

Sky News went live to the research ship, where onboard historian Dan Snow described Shackleton’s vessel as a “once-in-a-lifetime discovery” and announced the project would seek legal protection so no one could remove anything or otherwise disturb the ship. Countless wrecks were now within reach, Snow added, saying, “We have a duty to protect them, because there are people out there, bad actors, who want to loot and desecrate.” He seemed unaware that the Endurance expedition’s primary funder had been hacking into shipwrecks and extracting their contents for more than a decade.

Clake’s spokesman says: “There are strict international laws of salvage, and as far as Anthony is concerned any entity which he invests in should adhere to them.”

In July, after getting an email from a Businessweek reporter laying out the details of his maritime career, Clake agreed to break his silence and go on the record. “I don’t do it for a living,” he said in a phone interview. “I find it interesting to use technology to solve problems under the sea.” He figured he’d done about 30 wreck salvages in all, sometimes as the main investor, sometimes as a minority investor, sometimes with his companies working on behalf of a client. On several occasions he’s worked privately with the owner of lost cargo, such as an insurer, in return for a salvage fee.

Clake seemed to have cooled on the idea of wreck hunting, saying he didn’t have any projects in the works but would reconsider if an opportunity arose: “If people come to me with one, maybe.” In his telling, the world had reached peak shipwreck and come out the other side.

His larger goal was for Ocean Infinity to be a world leader in undersea technology. The modern UK has become too afraid of risk to produce champions, he said. “I want to take things further. That’s a personality trait.”

During his brief phone call with Businessweek, Clake couldn’t articulate a clear answer to the fundamental question: Why bother? For all he’s invested, it isn’t clear he’s made real money from wrecks. Most of his finds, by his own admission, have never been revealed. And while it’s impossible to say for sure, given how widely salvage awards vary, it isn’t clear he’s made real money from the wrecks. The most impressive finds have yielded more headaches than profit, and any sums he’s made look trivial compared with the $62 billion managed by Marshall Wace. Surely there are other datasets less fraught with peril.

Emson, who as Robert Fraser’s chairman first brought shipwrecks to Marshall Wace, thinks he knows the answer. An old-school merchant banker, he played a significant role in directing money from the financial markets to wreck hunting, and he worked closely with Clake at the time. He’s seen it happen before: When successful businessmen realize they can reach across the centuries, touch history and earn back many times what they put in, they get a feeling they want to experience again and again.

“You know why?” Emson asks. “It’s f—ing treasure fever.” —With Todd Gillespie, Ragnhildur Sigurdardottir and Ken Parks

More On Bloomberg

[ad_2]

Source link