[ad_1]

An Eli Lilly drug if approved for weight loss could become the best-selling drug of all time, but concerns are mounting about who will actually be able to afford it.

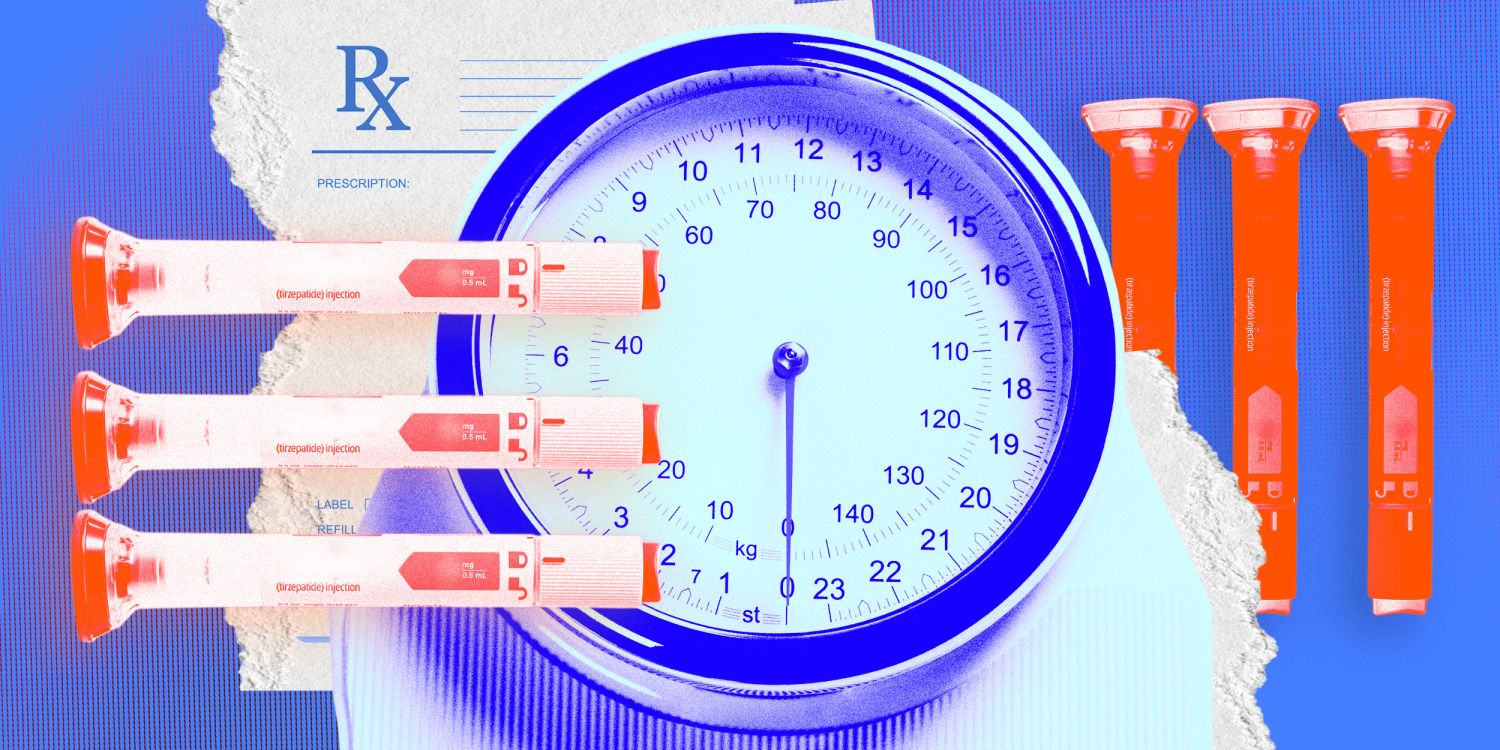

Experts are confident that the drug, called tirzepatide, will be granted approval by the Food and Drug Administration sometime next year. If that’s the case, it would join two other popular — and expensive — recently approved weight loss drugs on the market, Wegovy and Saxenda, both from the drugmaker Novo Nordisk.

Annual sales of tirzepatide could hit a record $48 billion, according to an estimate from Bank of America analyst Geoff Meacham. Another Wall Street analyst, Colin Bristow at UBS, estimated the drug would reach $25 billion in annual sales — a figure that would still surpass the record $20.7 billion set by AbbVie’s rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira in 2021.

Kelly Smith, a spokesperson for Eli Lilly, declined to comment on what tirzepatide will cost. Outside experts said it is possible the drugmaker could price it similarly to Wegovy, which carries a list price of around $1,500 for a month’s supply, and Saxenda, which costs about $1,350 for a month’s supply.

If the FDA confirms the drug’s effectiveness, a “fair” price for tirzepatide could be around $13,000 annually, or around $1,100 a month, said Dr. David Rind, the chief medical officer for the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a research group that helps determine fair prices for drugs.

The drugs have been shown in clinical trials to be highly effective for weight loss. All three drugs — which are given as injections — work in a similar way: They’re a class of drugs called GLP-1 agonists, which mimic a hormone that helps reduce food intake and appetite.

However, Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide also imitates a second hormone, called GIP, which along with reducing appetite, may also improve how the body breaks down sugar and fat.

A phase 3 clinical trial found a high dose of tirzepatide helped patients lose 22.5% of their body weight on average, or about 52 pounds, better than any medication currently on the market. Most patients in the trial had a body mass index, or BMI, of 30 or higher. In trials, Wegovy and Saxenda reduced body weight by around 15% and around 5%, respectively.

Are weight-loss drugs covered by insurance?

At lower doses, all three of the drugs are already approved to treat diabetes.

- Tirzepatide is sold under the name Mounjaro for diabetes.

- Semaglutide, when marketed for weight loss, is sold at a higher dose and called Wegovy; at a lower dose, it’s marketed for diabetes and sold as Ozempic.

- Similarly, a higher dose of the drug liraglutide is sold under the name Saxenda for weight loss, and at a lower dose, it’s sold as Victoza, for diabetes.

With the exception of Mounjaro, which was approved earlier this year, the versions of the drugs used to treat diabetes are covered by most insurance.

That’s not always the case when they are prescribed for obesity.

Obesity carries a unique stigma, said Dr. W. Scott Butsch, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. Many physicians, he said, still see it as a behavioral problem rather than a medical one.

That belief — in addition to older anti-obesity medications not being very effective — has made insurers reluctant to cover many of the new therapies, he said.

“You have a bias,” Butsch said, adding that insurance companies ask for more proof of the benefits of anti-obesity drugs than they normally would for other kinds of medications.

Some insurers may select one of the weight loss drugs and offer coverage, he said, but they often restrict access only to patients who meet a certain threshold, such as a BMI greater than 30.

What’s more, Butsch said, not everyone responds the same way to any given weight loss drug. If the drug covered by insurance isn’t effective for that patient, there are usually no other drug options left, he said.

Dr. Holly Lofton, the director of the weight management program at NYU Langone Health, regularly prescribes the new drugs to her patients but many, she says, are denied coverage by their insurance. “Patients tell me that it appears to them as if insurance companies want to wait until they get so sick that they have more of a necessity for a medication,” she said.

Lofton said that some of her patients will end up spending thousands of dollars out of pocket for the medication for a few months as they negotiate with their insurer to get coverage. Patients usually aren’t reimbursed by their insurance plan for the money they’ve already spent on the drugs, she added.

Dr. Fatima Stanford, an obesity medicine specialist and the equity director of the endocrine division at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said that private insurance coverage for anti-obesity medications is spotty, with treatments often restricted to the most expensive plans.

Medicare does not cover them. Anti-obesity drugs are not a mandatory Medicaid benefit, though some states have opted to include them, she said.

Obesity is considered a chronic illness, and like any other chronic illnesses, most patients are expected to take the medication for their entire lives — a great financial burden if they are forced to pay out of pocket, Stanford said.

The only people who will likely be able to afford a drug like tirzepatide on their own, she said, will be the “very rich.”

Despite the barriers to access, UBS analyst Bristow said he still expects tirzepatide to be a blockbuster drug for obesity, noting that the U.S. is already seeing supply shortages for the drug as a diabetes injection.

“It’s pretty clear how strong the demand is,” he said.

What needs to change?

Lofton, of NYU Langone Health, said insurance coverage of anti-obesity drugs may not improve until more people in the medical field change how they view obesity. It’s not something that diet, exercise or sheer willpower can fix — instead, it’s a dysregulation of fat cells in the body, she said.

Bias and stigma about obesity run rampant throughout the medical community.

It’s “evident across all health professionals, including physicians, nurses, dietitians and others,” said Lisa Howley, an educational psychologist and the Association of American Medical Colleges’ senior director of strategic initiatives and partnerships.

A review published last year in the research journal Obesity found that health care professionals hold implicit and/or explicit weight-biased attitudes toward people with obesity.

But shifting the opinion of the medical community — and with it, insurance companies — is extremely difficult. Requiring anti-obesity drugs to be covered by insurance may require legislative action, Stanford said.

In 2021, lawmakers in the House of Representatives introduced The Treat and Reduce Obesity Act, which would have allowed the federal government to expand Medicare Part D coverage to include anti-obesity medications. The legislation had 154 bipartisan co-sponsors, according to Congress.gov, but did not receive a vote on the House floor before the term ended.

America’s Health Insurance Plans, or AHIP, a trade group that represents insurance companies declined to say whether it would support coverage of tirzepatide should the drug win FDA approval next year or other anti-obesity drugs.

“Health insurance providers routinely review the evidence for medications and surgical treatments for obesity, and they offer many options to patients — ranging from lifestyle changes and nutrition counseling, to surgical interventions, to prescription drugs,” said David Allen, a spokesman for AHIP.

Butsch, of the Cleveland Clinic, said he is hopeful insurance companies will cover tirzepatide.

“We’re seeing really for the first time highly effective anti-obesity medications,” he said. “The benefit is real.”

[ad_2]

Source link