[ad_1]

Just a few hours earlier, the body of Vera was lying around the corner, shattered by a shell blast. She had left her home to pick up supplies from a local shop but ended the trip lifeless in the snow, her clothes torn, still wearing her wedding ring.

She was 42 and had one child, a 14-year-old son.

“There was an explosion, we saw nothing, but then we started to look out for people. Vera had left for the shop — we didn’t realize it was her,” said Ludmila, 73, a neighbor. She was concerned about Vera’s son seeing the body “because she’s really in bad shape, her body is bloody and torn apart.”

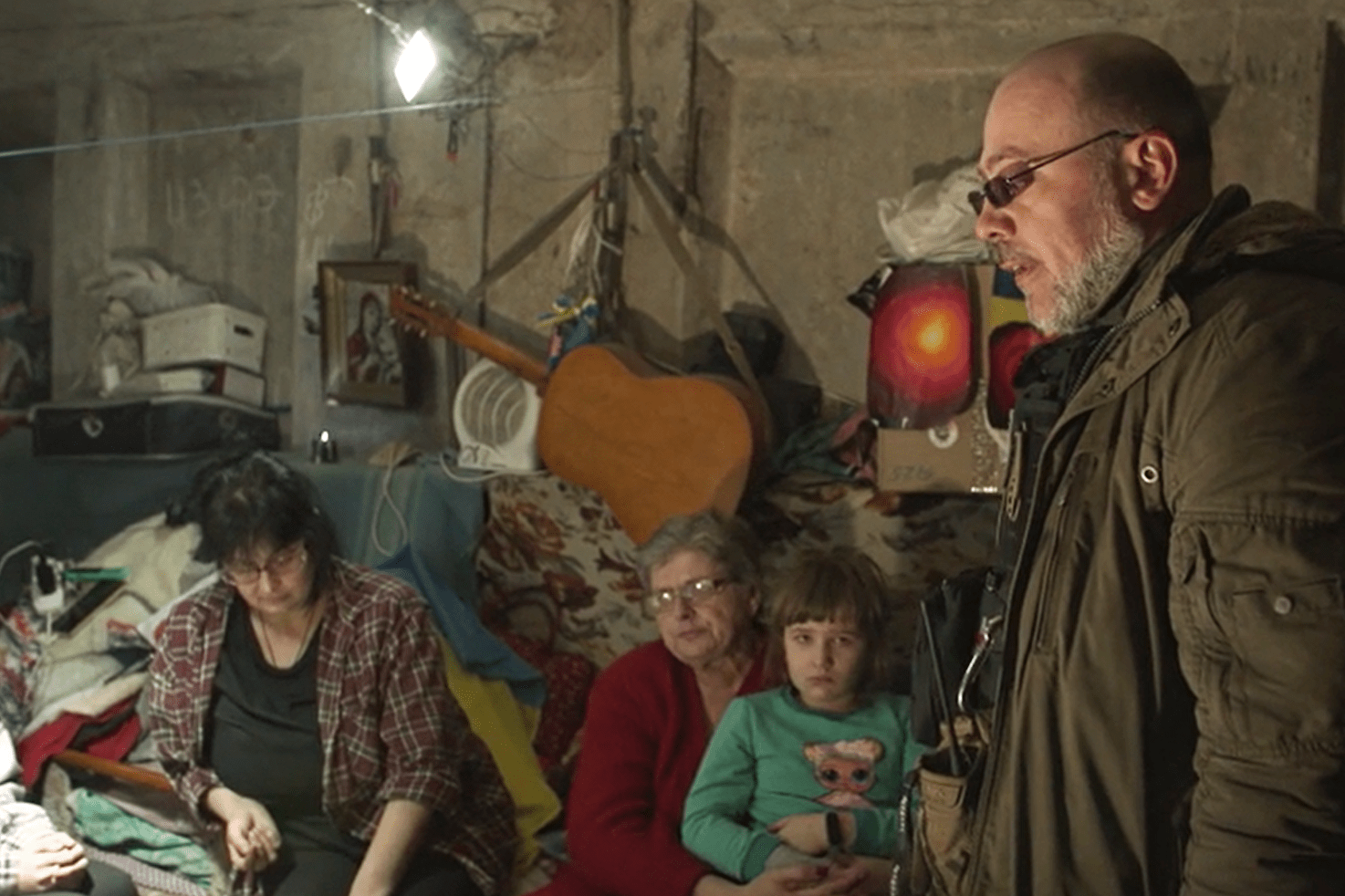

People here are reluctant to leave for safer areas that are out of the way of the Russian offensive, or can’t afford to make the trip. Others tried to leave but ended up back here having failed to make life work as displaced Ukrainians.

One man making the trip was 75-year-old Mykola Yaroslavstev, whose sons are all fighting in the war. He trudged through the snow with his walking stick as his friend Oleksandr, a sprightly chain-smoking 76-year-old, pulled his bags on a sled to a van waiting to take him to Odesa to stay with his daughters-in-law.

Why not leave sooner?

“Because I’m 75 years old and stubborn. I pray for better but it will not get better. Yesterday, my neighbor’s house was hit and now it doesn’t exist at all,” Yaroslavstev said.

That destruction was a message that he interpreted as: “So, old man go away, otherwise your grandkids will not see their granddad, but a piece of meat.”

Though Ukrainian authorities have urged many people still living near the front lines to leave, officials are sympathetic.

“It’s really very hard for people to be here. They don’t want to leave the town where they were born. The example of Vera is a very obvious example. She was just a person who went out to buy some food and she was killed,” said Serhiy Chaus, 42, head of the Chasiv Yar Military Civilian Administration.

[ad_2]

Source link