[ad_1]

Credit Suisse directors last month made the trek up the Swiss Alps for their annual off-site gathering in the spa town of Bad Ragaz, famous for its healing waters.

After a bruising few years in which the bank lurched from crisis to crisis, chair Axel Lehmann and the board had finally decided on a turnround plan.

The only question remaining was who would drive that change. They had concluded that chief executive Thomas Gottstein, who had his own health problems, was no longer the right man for the job.

That was settled on Wednesday with the promotion of Ulrich Körner, a former UBS executive who joined last year to run the asset management division. He beat out two internal rivals, investment bank boss Christian Meissner and Francesco De Ferrari, head of wealth management, people familiar with the matter told the Financial Times.

Körner was picked because of his reputation for dispassionate cost-cutting and operational execution, the people said, deemed essential in a bank that has spiralled out of control, unable to stem the flow of scandals and with its shares at a three-decade low.

People close to the 59-year-old Swiss executive say he earned the nickname “Uli the knife” during his 11 years at UBS, where he helped restore discipline in the wake of a rogue trading scandal that led to losses of $2bn and the chief executive’s ousting.

A person familiar with the matter said Körner narrowly missed out on UBS’s top job to Sergio Ermotti a decade ago. When he takes over at Credit Suisse on Monday he will have the chance to revive another ailing Swiss lender. “He clearly has unfinished business,” said one former UBS colleague.

His task is daunting. During Gottstein’s two-year tenure, Credit Suisse shares plunged 60 per cent and the bank was haunted by scandals old and new.

It lost $5.5bn from the collapse of family office Archegos, is still trying to recover $2.7bn of client money after the failure of Greensill Capital, was fined for its role in the $2bn Mozambique “tuna bonds” scandal and became the first Swiss bank to be found guilty of a corporate crime after it was found to have laundered money for a Bulgarian cocaine cartel run by a former professional wrestler.

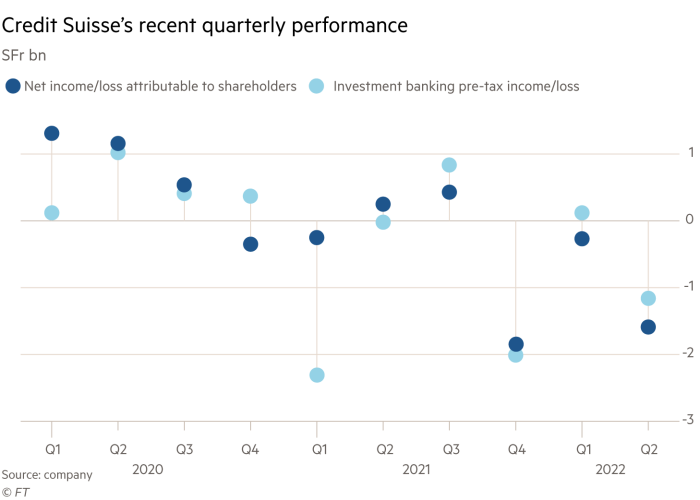

The financial performance has been equally bleak. After making a SFr2bn ($2.1bn) loss in the fourth quarter last year, it has lost a further SFr1.9bn this year. It has issued profit warnings in six of the last seven periods.

Gottstein’s departure means all but one member of the dozen-strong executive board he installed in early 2020 is gone, or soon will be.

“While Mr Gottstein inherited a number of problems, the way in which the firm reacted to these and the subsequent strategy adopted has left the bank in a weaker position with significant franchise erosion across all divisions, most notably the investment bank,” said Citigroup analyst Andrew Coombs.

Top of Körner’s lengthy to-do list is a brutal cost-cutting exercise that will lead to a much-diminished investment bank and strip out as much as 20 per cent of the bank’s annual spending to less than SFr15.5bn.

Shareholders and Credit Suisse’s 45,000 global workforce will be watching anxiously to see if Körner and Lehmann — who worked together at UBS — will be able to arrest the decline of a national champion that has taken on Deutsche Bank’s mantle as world’s most scandal-prone lender.

People familiar with the new strategy, which will be unveiled in more detail in October, said another focus would be cutting what is considered to be bloated and inefficient technology and operational divisions.

The change in leadership was announced at the same time as the bank reported a third consecutive lossmaking quarter. The SFr1.6bn group-wide loss, significantly worse than the SFr206mn expected by analysts, was driven by a SFr1.2bn hit from Credit Suisse’s investment bank, the source of many of its recent woes.

Credit Suisse’s latest strategic review — its second in less than a year — aims to slim the investment bank to focus on capital-light advisory work to support the group’s three other business lines: wealth management, asset management and the Swiss domestic bank.

The plan is being hashed out with support from advisers at Centerview Partners, whom the bank’s previous leadership had recruited to devise a more sustainable strategy.

The move risks alienating investment bankers. Meissner, head of the division, is planning to step down after an interim period, despite having joined little more than a year ago, the FT reported on Tuesday.

Körner and Lehmann have said they are considering an exit or sale of the bank’s securitised products business, which used to be one its most profitable. But analysts cautioned that while revenues are quick to disappear as trading units are shut down, the costs stick around for much longer.

“We expect exit costs from this business, which has $20bn of risk-weighted assets and $75bn of leverage exposure, could be sizeable,” said Citigroup’s Coombs. Third-party capital is being sought “presumably to reduce the magnitude of exit and restructuring costs, but we question who would step in and how this relationship would work”.

Credit Suisse investors have long called on the group to pull back from investment banking, saying its returns do not justify the costs of running the business or the frequent scandals.

“We are encouraged that management is taking steps to realise the inherent value in Credit Suisse by improving upon their strengths and shedding their weaknesses,” said David Herro, vice-chair of US asset manager Harris Associates, the bank’s largest shareholder.

Vincent Kaufmann, chief executive of Ethos Foundation, which represents shareholders owning about 5 per cent of Credit Suisse stock, said scaling back the investment bank was long overdue and mimicked UBS’s successful shift to wealth management a decade earlier.

“Having two former UBS executives now running Credit Suisse is an acknowledgment that UBS made the right turnround 10 years ago,” he said. “They can change strategy and leadership, but the real change needs to be on culture. They need to show it’s working.”

However, another top-10 shareholder gave a less optimistic assessment.

“My view is the company is listless, it has no effective leadership,” the person said. “My forecast is that the bank will be sold. This will not work out and the regulator will force a transaction.”

Some trace Credit Suisse’s problems back decades to its attempt to break into Wall Street by building a stake in First Boston, taking majority control in 1988 and branching out from its Swiss private banking roots. It was then run by a series of US investment bankers including John Mack and Brady Dougan.

“Twenty years ago we lost our soul. We wanted to play in the NBA, that is how we saw investment banking,” said one veteran wealth manager. “And not only did we buy an investment bank, who were the next CEOs? They all came from there — what do they know about private banking? Banana trees are not going to produce cherries.”

“We need to go back to the essence of our core business and regain our soul,” he added. However, there is “little room for strategic manoeuvre today with the capital position, business mix, legacy misconduct issues, provisions and the loss of vast human capital”.

The bank sought a new direction in 2015, recruiting insurance executive Tidjane Thiam. After a promising start where he set about de-risking the investment bank and shifting the strategic focus to wealth management in Asia, he became mired in a corporate spying scandal that undermined his turnround and ultimately cost him his job.

Credit Suisse then recruited former Lloyds chief executive António Horta-Osório for a fresh start. But he lasted less than a year as chair, quitting in January after losing the confidence of his board when it emerged he had breached Covid-19 quarantine rules to attend sports events with his family and used company-funded private jets for personal trips.

Internally, many in Zurich hope the sober Körner will bring an end to such lurid scandals and address a cavalier approach to risk management that has characterised its recent past.

“Credit Suisse has always been too small to compete with Wall Street, so we have taken risks that are too great,” said a Credit Suisse compliance professional, citing last year’s twin crises of Greensill and Archegos.

“Some of them pay off for a while. But it is like Russian roulette — the sixth bullet always kills you.”

[ad_2]

Source link