[ad_1]

German states are rethinking how their police forces use software made by Palantir over privacy concerns, as the US data group’s ambitions to expand its European business come under strain.

Two states — Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia — told the Financial Times that they are reviewing use of Palantir’s software after a ruling that laws allowing the use of data mining by police forces were too broad and infringed on individuals’ privacy.

That ruling was made last month by Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court against Hesse and Hamburg and has already forced those states to begin overhauling their use of software made by Palantir, which is best known for its contracts with US security organisations including the CIA.

The German state moves have dealt a blow to the $17bn data analytics company, led by chief executive Alex Karp and co-founded by Peter Thiel, the tech investor and prominent backer of US Republican political candidates.

Palantir has sought to grow in Europe through work for governmental clients. It is the frontrunner for a forthcoming £400mn data contract with the UK’s NHS and its other clients have included the Danish police and the law enforcement agency Europol. German police forces have said they intend to continue using Palantir’s software.

But wariness from privacy advocates in Europe has hampered the expansion effort. Karp, a German speaker who holds a doctorate from Frankfurt’s Goethe University, said in a February earnings call that Europeans are “a lot less friendly to new innovations”.

“That felt to me like they’re throwing in the towel on Europe,” said Tyler Radke, a software equity analyst at Citi, about Karp’s comments. “Companies don’t just throw in the towel because of macro[economic factors] . . . privacy [concerns] could be part of that.”

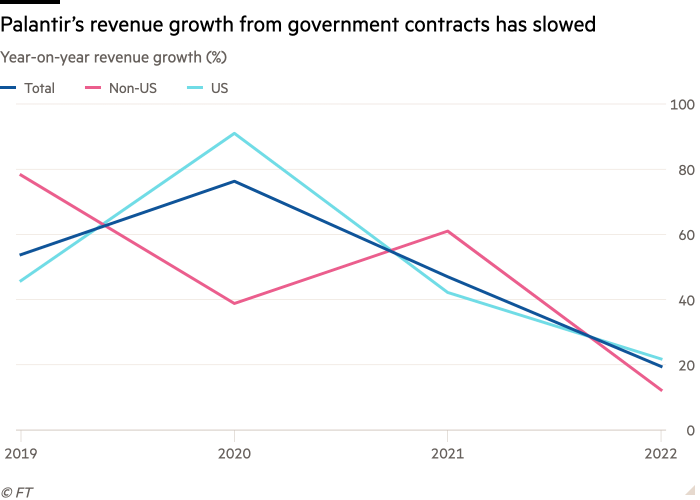

Growth in Palantir’s government contracts business, which makes up over half of its revenue but of which over three quarters comes from the US, slowed from 47 per cent in 2021 to 19.5 per cent in 2022. Non-US government spending rose just 12 per cent from 2021 to 2022, compared to a 61 per cent rise the previous year.

In Germany, mistrust of state surveillance runs deep, given memories of the Stasi secret police and Hitler’s Gestapo.

Like Palantir’s other law enforcement clients, police in Hesse, a state in central Germany with a population of around 6mn, use Palantir’s Gotham software, named after the fictional city home to superhero Batman, to sift through vast sources of police data.

Since it was first deployed in 2017, the so-called HessenDATA system has helped foil a 2018 Islamist terrorist attack and uncover a paedophile ring in 2020, according to the state’s interior minister Peter Beuth.

“Our police must be able to sift through their own data quickly and efficiently to avert threats of the highest legal interests,” Beuth said. “The police work of the future must deal efficiently with large amounts of data.”

But the constitutional court found that using Gotham “allow[s] the police, with just one click, to create comprehensive profiles of persons, groups and circles”, which could subject innocent people — such as those with links to criminals — to police investigation if they are wrongly identified as subjects.

Now, Hesse’s police cannot conduct automated data analysis until its government has rewritten its legislation. Hamburg has not yet started implementing the software but it must also reform 2019 laws allowing for its use.

The ruling also threatens Palantir’s expansion to other states. Bavaria signed a €25mn framework agreement with Palantir in 2022 that other German states can choose to join, speeding up Palantir’s adoption across the country.

Bavaria said it had concluded “in principle” that it would need to change its policing law, but the details would depend on the constitutional court.

In North Rhine-Westphalia, which signed a Palantir deal worth more than €20mn in 2020, the ruling has prompted the local government to ask legal experts whether it needs to change its laws on a state level, a spokesman said. It is waiting for the outcome of its own constitutional court ruling, after a similar complaint was brought.

Last month’s ruling could make Palantir’s software less useful, according to Bijan Moini, head of legal at Berlin-based NGO Society for Civil Rights, which brought the case.

Hesse used its software 14,000 times in 2020 but usage will now fall as data-mining is reserved for serious crimes, Moini said. “When the range of problems that you can address with Gotham is reduced, it becomes less attractive and even more [German states] may be critical of buying into the contract,” he added.

Activists elsewhere in Europe do not anticipate immediate repercussions beyond Germany. Palantir expects the ruling to reassure states that its tech can be used within the framework laid out by the constitutional court.

Palantir said: “We welcome the court’s effort to clarify under which circumstances and in which ways police authorities can process their lawfully collected data. Palantir’s software can be flexibly adapted to new legal frameworks thanks to its high configurability.”

The ruling sets a precedent for opponents of data mining, said Ilia Statista, a senior legal officer at Privacy International, opening the door for further challenges.

“The automation of policing has only just begun,” said Misbah Khan, who is the German Green party‘s rapporteur on data protection and privacy rights. “We have to ask ourselves whether the use of data mining and artificial intelligence simply complements traditional police work, or whether entirely new possibilities for invasion of privacy are emerging.”

[ad_2]

Source link