[ad_1]

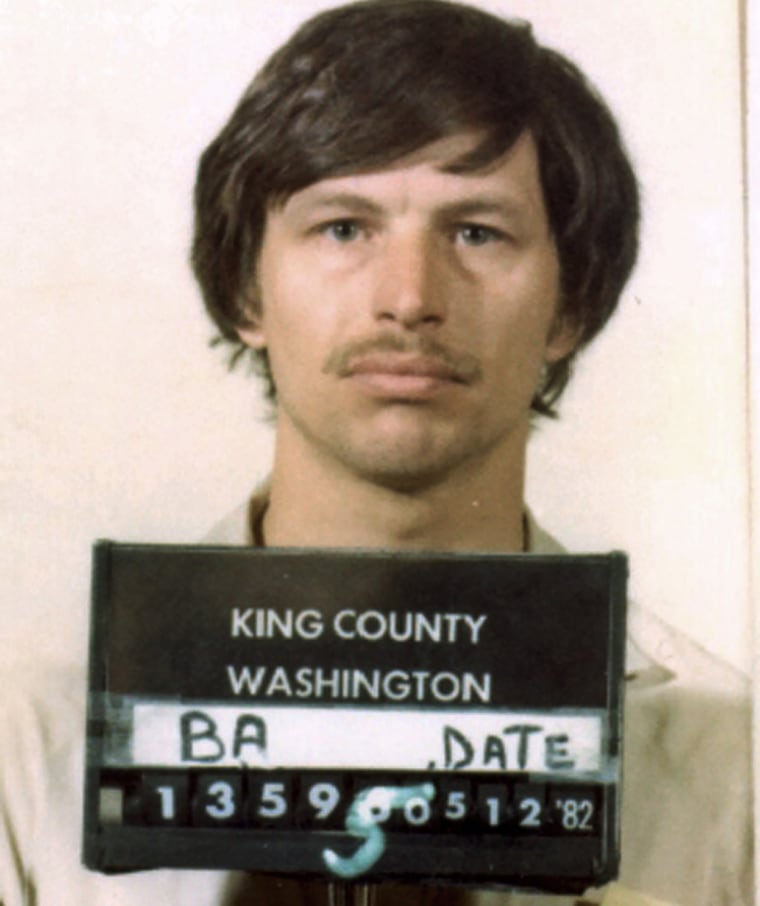

1982-86: A decision about evidence

In July 1982, the body of Ridgway’s first known victim was pulled from the Green River in suburban Seattle, a pair of blue jeans knotted around her neck.

Embedded in the denim used to strangle 16-year-old runaway Wendy Lee Coffield were the tiny spheres of spray paint that would take more than two decades to detect.

After four more bodies were found dumped in and along the Green River within a month, the King County sheriff assembled a task force to track down a serial killer.

The killer kept preying on vulnerable women and girls, many of whom were runaways or had been involved in street prostitution, leaving the bodies in remote, wooded stretches. Investigators compiled a list of hundreds of potential suspects and amassed a mountain of evidence from the dumpsites, turning much of the material over to state forensic scientists for analysis.

Ridgway first came to the task force’s attention in 1983, when 18-year-old Maria Malvar disappeared after she got into a pickup truck with a man on Pacific Highway South. Her boyfriend and pimp later spotted what he thought was the same truck in front of Ridgway’s house and reported it to police.

Ridgway told a detective he knew nothing about Malvar’s disappearance, but he kept resurfacing in tips and brushes with sex workers over the next several months. He voluntarily spoke with detectives and acknowledged he’d been arrested before for soliciting a prostitute. He said he’d continued to routinely pick up girls working the street and had even encountered two of the killer’s presumed victims. But he denied having harmed them. In 1984, he agreed to take a lie detector test — and passed.

By then, the killer had left behind key microscopic evidence that could have helped unmask his identity, records and interviews show. Along with the jeans used to strangle Coffield, the paint spheres were trapped in the weaves of fabric eventually found with seven other bodies and bones, records show. A purple shirt. A pair of jeans. A black knit sweater.

But with the volumes of evidence, the staffing constraints and the workload of other cases statewide, crime lab officials had to choose what evidence to analyze, said Cwiklik, the lab’s trace evidence supervisor at the time.

They opted to focus on analyzing hairs and fibers, which “usually would have been the most fruitful,” Cwiklik said in a recent interview.

The analysts assigned to the case “actually did an amazing job” of sorting, analyzing and comparing thousands of individual hairs, fibers and chunks of paint and other collected debris, she said.

But focusing analysis on hairs and fibers meant the lab “basically ignored” smaller particles and dust on clothing and other items, Cwiklik said.

In early 1985, Ridgway drew suspicion again after another woman reported that a man who showed her his Kenworth employee identification card tried to strangle her after he had paid for sex in 1982. When a detective questioned him, Ridgway claimed he choked the woman only after she bit him. The woman declined to press charges, according to the detective’s report.

The same year, Palenik, the renowned trace evidence expert, learned about the case. Palenik, then a senior researcher at the Chicago-based McCrone Research Institute — a leader in microanalysis — taught workshops around the country. He’d just finished teaching a basic forensic microscopy course at the crime lab in Seattle when George Ishii, then the director, told him about the Green River murders, Palenik said in a recent interview.

Before he left town, Palenik said, Ishii vowed to seek his help if a suspect emerged. But he never heard about the case again from Ishii, who died in 2013. Ridgway is known to have killed at least four women after 1985, when Palenik visited Seattle.

“Imagine in ’85, after I was out there, if George sent this stuff back to us, we’d find and identify the spheres as this unusual urethane paint,” Palenik said. “And then when they bring in a suspect and it’s Gary Ridgway — well, where does he work? He works at a place where he sprays the very same unusual paint on trucks all day.”

But without that forensic testing, Ridgway slipped through investigators’ grasp and kept killing.

1987-90: ‘We should have done it’

By 1987, Ridgway’s penchant for prostitutes and past brushes with known victims and other tips were enough to help investigators get a warrant to search his home, vehicles and workplace.

In an affidavit, investigators wrote that they wanted to compare trace evidence collected from various dumpsites that might be tied to Ridgway, including green polyester carpet fibers and aluminum fragments.

But the hair, fibers, clothing and other evidence that were seized didn’t definitively tie Ridgway to any victims, and he slipped back into the slush pile of suspects as the decade ended.

In hindsight, Cwiklik said, the crime lab should have shifted its focus from hairs and fibers and turned to analyzing smaller particles in the trace evidence recovered from the dumpsites.

By 1990, Cwiklik said, the crime lab was using an infrared microscope, capable of detecting finer details than an optical microscope. For years, the lab also had been using techniques to capture smaller fractions of trace evidence that could have helped to detect the paint spheres, she said. But it still would have needed an outside specialist, like Palenik, to identify and trace them back to their source, she said.

“Really, we were capable of finding these things, but we didn’t because we didn’t look at the small, small fractions,” she said. “It always bugged me that we didn’t do that, but it would have been hard to argue that we should prioritize that.”

“But later on, when nothing was fruitful,” she said, “we should have done it.”

1990s: A rejected request

By the early 1990s, when a new wave of bodies and bones were found, the Green River Task Force had already disbanded. But a smaller group of detectives who feared the killer was still at work quietly kept the probe alive. They focused on a prime suspect: Ridgway.

In November 1992, detectives formally requested that the crime lab compare hairs collected from Ridgway to those recovered from the new wave of victims, according to a detective’s memo to the lab obtained through a public records request. But officials for the crime lab, which by then had spent years futilely analyzing hairs and fibers in the case, rejected the request as a pointless endeavor, retired King County sheriff’s Detective Tom Jensen said.

Jensen, who dedicated most of his career to the case, was stunned to learn recently from an NBC News reporter that the capability to detect the paint spheres that linked Ridgway to some of the victims had existed years earlier.

He couldn’t recall lab officials’ ever having mentioned to detectives that smaller particles of trace evidence hadn’t been analyzed, he said.

“I should think we would have done the testing if we knew about it,” Jensen said. “We were doing everything we could to come up with a shred of evidence.”

As the ’90s wore on, Jensen was left to investigate the Green River murders on his own as leads dried up.

Jensen’s list of the killer’s suspected victims grew to nearly 90, including dozens of homeless or drug-addicted girls and women who’d disappeared or were dumped in remote places across western Washington.

Near the end of the decade, the killings seemed to stop. But they hadn’t.

When Patricia Yellow Robe’s body was found in bushes outside a wrecking yard south of Seattle in 1998, she wasn’t considered a victim of the killer. The medical examiner ruled her death an accidental overdose.

Yellow Robe grew up in Montana as the oldest of nine siblings in a family splintered by alcoholism. By 38, she’d been in and out of rehab and had suffered chronic health problems. She spent her last days couch-surfing and frequenting dive bars, police records show.

[ad_2]

Source link