[ad_1]

2023 was the year that chief sustainability officers (CSOs) struggled to make the business case for sustainability amid a global economic slowdown and conflicting business priorities as geopolitics wormed its way into the boardroom.

Some companies scaled back their climate ambition. Big polluters such as BP and Shell, and multinational consumer brands such as Canon, rolled back decarbonisation pledges, while major banks, including Standard Chartered and HSBC, stepped away from the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), the United Nations-backed organisation that aligns net-zero targets with a climate-safe planet, over concerns that SBTi validation could hinder their ability to finance fossil fuels.

But other companies ramped up climate ambition despite governments postponing or adjusting climate targets. In November, 367 finance firms and multinational companies worth US$33 trillion joined forces to demand science-based targets to limit global warming to 1.5°C, including carbon intensive firms such as Dow Chemical, Nippon Steel and JD.com.

But the life of a CSO didn’t get any easier in 2023, amid resource constraints and rising expectations of what the sustainability function should deliver for the business. Eco-Business spoke to CSOs and sustainability consultants to get a sense of the things that kept the corporate conscience awake at night this year.

What is a CSO actually for?

Expectations for what CSOs should be delivering for the business grew in 2023, as the function ballooned in importance amid investor and consumer pressure to raise corporate climate ambition as governments dithered. But sustainability executives struggled with how to define their role. CSOs cannot be all things to all people, and the sustainability agenda is becoming so broad and so diverse that it is getting ever more difficult for CSOs to describe and define what it is that they do.

ESG backlash

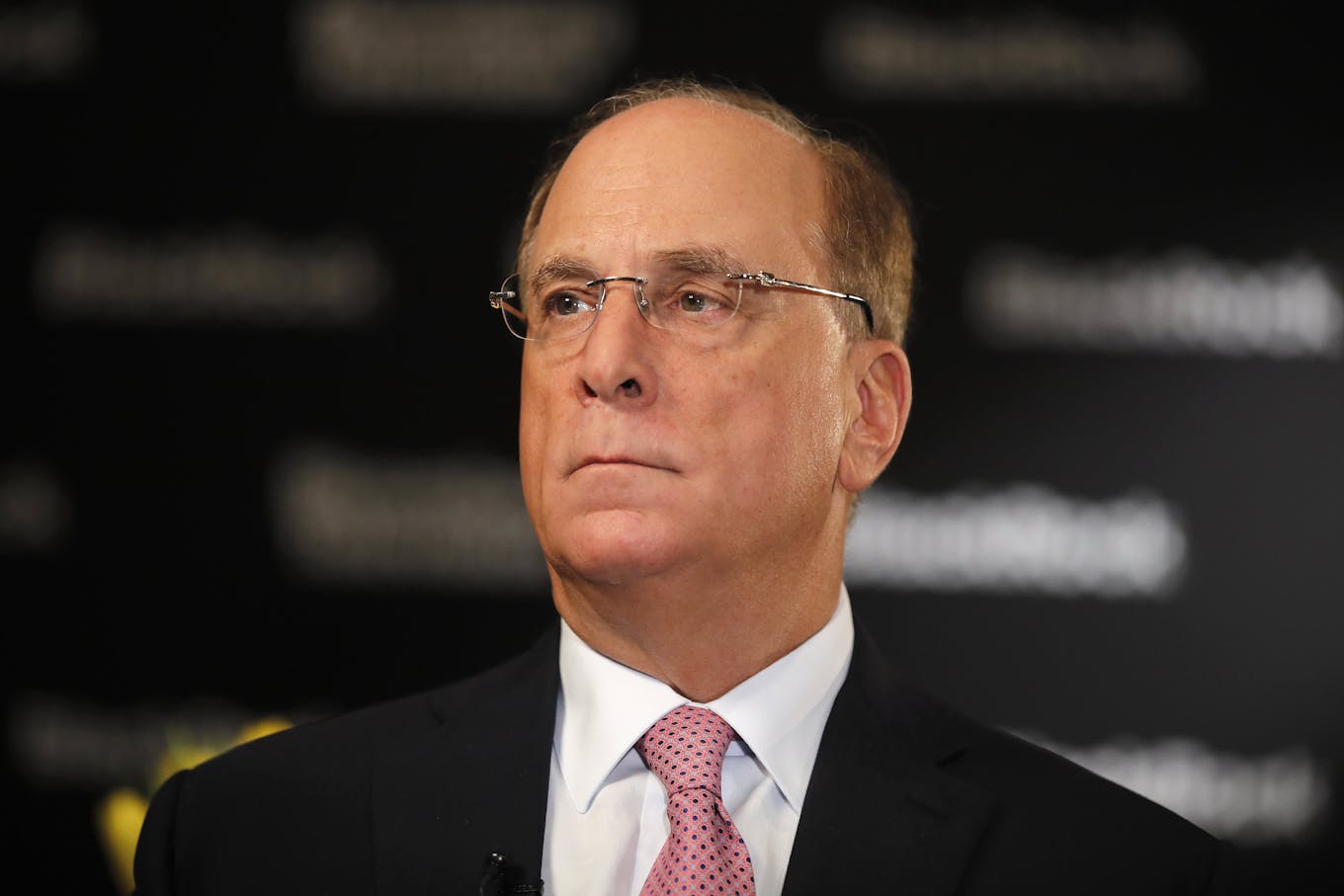

Blackrock CEO Larry Fink has become a lightening rod for criticism of ESG investing in the US. Image: Stefan Wermuth/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The politically-motivated backlash against environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing in the United States – which dragged the name of Blackrock CEO Larry Fink through the mud and prompted him to stop using the acronym – did not directly affect many CSOs in Asia. But it didn’t make their lives any easier. Particularly during budget meetings. How to gain board approval for ESG when one of the world’s supposed leading countries on corporate sustainability is headed in the other direction?

The business case for net-zero: On thin ice

Many companies have made net-zero pledges with little understanding of how to get there, leaving a gap between expectation and reality in the boardroom. Getting science-based net-zero targets approved requires board, if not c-suite level approval. But CEOs rarely come to the table with an understanding of the financial dynamics or the moral imperative of net-zero. According to Valerie Phua, senior sustainability consultant at Paia Consulting, a Singapore-based sustainability consultancy, one question CEOs may ask is whether they can buy all the renewable energy certificates (RECs) or carbon credits the company needs one year before their target net-zero year – because RECs and carbon credits are much cheaper than energy efficiency measures and onsite renewable energy. What has shifted the needle most for net zero ambitions this year has been the prospect of revenue loss due to rising customer expectations, and reputational damage, Phua said. CSOs that make an effective business case are more likely to secure the investment needed to decarbonise business operations, she says.

Competence greenwashing

Perhaps the most common gripe among CSOs this year is hiring from a limited talent pool in which candidates claim to have mastered a complex and constantly changing field after going on a six-week course. Sure, everyone bigs-up their CV. But there are few sectors in recent history that have produced so many overnight experts. This is a particular concern in Asia, where industry-watchers say people have been promoted too quickly into senior roles with very little sustainability experience, leaving them exposed in board meetings when they are asked to justify their existence.

Geopolitics

As if CSOs didn’t have enough to worry about. The Ukraine war and tensions between China and the United States wormed their way into boardrooms this year, prompting some sustainability experts to suggest that an extra “G” should be added to ESG: Geopolitics.

The Science Based Targets Initiative

John Haffner (right), deputy director for sustainability at Hong Kong property developer Hang Lung Properties, spoke on behalf of real estate firms in opposition to SBTI’s proposed new rules at the ReThink event in October. Image: ReThink

The gold standard for decarbonisation target-setting lost a few CSO friends in 2023, particularly in Asia. Hong Kong’s real estate sector lobbied against a proposed SBTi rule change that would have meant buildings firms in Hong Kong – and elsewhere in Asia – could not count carbon-cutting measures such as buying RECs and clean energy power purchase agreements made overseas in their net-zero calculations – a big problem for companies in jurisdictions with fossil fuels-based grids with a limited supply of RECs. SBTi seems to have relented in the latest version of its building sector guidance, and will now allow companies to use either location- or market-based accounting for Scope 2, or indirect emissions from the electricity they use. Even so, many companies in Asia struggled to get their net-zero targets approved by SBTi in 2023, and feel that the organisation favours Western businesses that have the luxury of cleaner grids. Others say SBTi is right to keep pushing companies to try harder to align with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degrees Celsius goal, and not rely on cheap and easy methods to decarbonise.

Greenwashing and greenhushing

One of the biggest fears any self-respecting CSO has is getting accused of greenwashing (see our story on the brands called out for greenwashing this year), particularly when it is unintended. CSOs do not want to greenwash, but poor alignment with the communications department – which in Asia is often where the sustainability function is parked – exposes brands to greenwashing risk. Rather than risk the reputational damage of getting called out, many brands preferred not to say anything at all about their sustainability credentials this year. But “greenhushing” stunts corporate transparency, dilutes the company’s potential climate impact and deters competitors from raising their game. One theoretical alternative to greenhushing that emerged this year is “corporate vulnerability”, where companies are honest about their failings and missteps in sustainability reports. Eco-Business has yet to see any evidence of this theory coming into practice.

Scope 3

Getting your own house in order is hard enough, but decarbonising the full value chain – which accounts for the lion’s share of emissions for most firms – was a thorn in the side of CSOs this year. Particularly oil and gas companies like Malaysia’s Petronas, which said it needed regulatory support to mandate emissions reporting across its value chain. “It’s not that we’re ignoring Scope 3 because we do understand that it is important,” said the company’s chief financial officer Liza Mustapha in September. “The challenge is understanding how to measure someone (else’s) utilisation of your product and … not being able to control how they use your product.” While two-thirds of the world’s biggest companies now have a net-zero target, just over a third (37 per cent) of net-zero targets fully cover Scope 3 emissions, according to Net Zero Tracker.

Sustainability events

While CSOs enjoy the networking, coffee break tittle-tattle and after-show cocktails, some do get the sinking feeling that sustainability events are echo chambers that preach to the choir. “The information swirls around the room, but doesn’t leave,” one Malaysia-based sustainability professional told Eco-Business. “Innovation is needed in the events space to get the problems we are facing and how to solve them into the mainstream. Events are currently not set up to do that,” she said.

Regulation

Keeping up with policymakers, particularly those based in Brussels, preoccupied CSOs in 2023. The European Union’s Deforestation Law (EUDR) gave CSOs working in forest-risk commodities such as palm oil, pulp and paper and soy plenty to think about, such as whether the EUDR undermines the role of certification in weeding deforestation out of supply chains. The EU’s proposed ban on the term “carbon neutral” without data to back up such claims also made CSOs with unconvincing “aspirational” decarbonisation plans feel uneasy.

The voluntary carbon market

A few articles in the Western press butchered the credibility of the voluntary carbon markets this year and made cheap and easy ways for businesses to decarbonise a whole lot more difficult to justify. Environmentalists, however, argued that carbons markets were in dire need of a shake up to bring some much-needed accountability to the emissions-reducing claims of suspect carbon projects.

Alphabet soup

The number of sustainability standards, taxonomies and frameworks CSOs must navigate as they work towards sustainability targets is befuddling for most – even though there are some signs of market consolidation, such as the merger of Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). CSOs feel they are spending too much time on this, rather than doing important things like actually helping their business to decarbonise.

Data digging

One of the trickiest things about regulated sustainability reporting, CSOs say, is getting their hands on reliable data. Making sure sustainability data is collected comprehensively and accurately is laborious and requires the soft skills of a diplomat to cajole various company departments into coughing up the necessary information while they’re busy doing their day jobs.

COP

COP28 President Sultan Al Jaber and participants applaud at the UNFCCC formal opening of COP28 in Dubai. Image: COP28 / Christopher Pike

Christiana Figueres, one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, said in September that the annual United Nations Conference of Parties (COP) have become “a circus”, and suggested that the ambition of the climate meetings could be better achieved by getting things done at home. As for CSOs, some say that COPs are not well set up for the discussions they need to help their businesses decarbonise and do their jobs better – so can’t justify the carbon footprint of flying half away around the world to witness politicians disagree over a single line of text that doesn’t change much.

Consultancies

Eye-wateringly expensive and what value do they really add? Sure, some consultancies are useful for helping companies chart the right decarbonisation pathways, meet regulatory requirements and write sustainability reports, but some CSOs wonder if the thousands, sometimes millions they pay a consultancy couldn’t be saved by bringing the expertise inhouse.

Have we missed any? Let us know by writing to news@eco-business.com. This story is part of our Year in Review series, which journals the stories that shaped the world of sustainability in 2023.

[ad_2]

Source link