[ad_1]

Qualifications and Skills

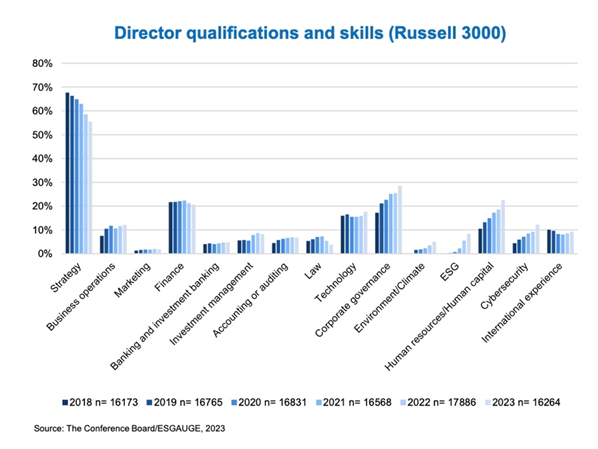

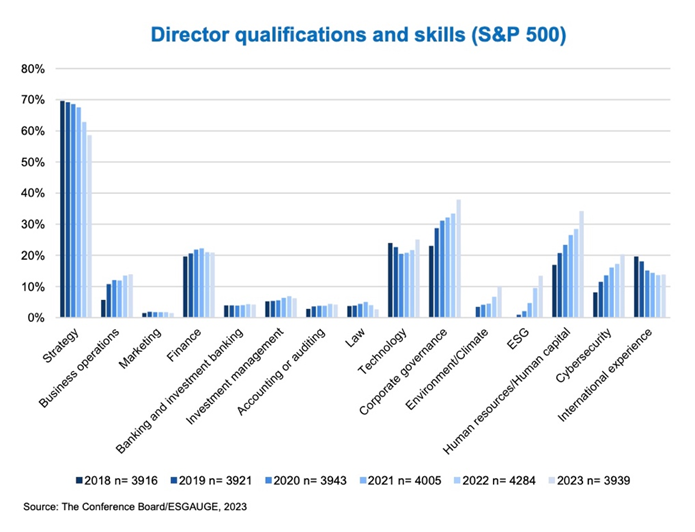

While business strategy is the most cited experience for directors, the share of board members whom companies report as having such expertise continues to decline. In the S&P 500, the percentage of directors with such experience—as reported in the proxy statement or other disclosure documents—declined from 70 percent in 2018 to 59 percent in 2023. In the Russell 3000, the decline was even more pronounced, from 68 percent in 2018 to 55 percent in 2023.

Decreased business strategy experience on boards is a worrisome trend, as approving the overall strategic direction of the company is a core responsibility of boards. Having such shared experience enables directors to “speak the same language” and collaborate effectively. Having a strategic lens for assessing business opportunities and risks as they arise also enables boards to maintain a steady course despite a changing environment and—often conflicting—demands.

By contrast, functional experience in ESG and other areas has increased in recent years. For example, in the S&P 500, directors with reported experience went up in governance (from 23 percent in 2018 to 38 percent in 2023), environment/climate (from 0 to 10 percent), ESG (from 0 to 13 percent), human capital (from 17 to 34 percent), and cybersecurity (from 8 to 20 percent). In the Russell 3000, experience also grew—albeit less sharply—in governance (from 17 percent in 2018 to 29 percent in 2023), environment/climate (from 0 to 5 percent), ESG (from 0 to 8 percent), human capital (from 11 to 23 percent), and cybersecurity (from 4 to 12 percent).

While having directors with functional experience in ESG areas can be beneficial, it should not be a substitute for core business competence. Directors who have strategic business acumen and a deep understanding of the board’s various responsibilities will be more effective in helping make the connection between the company’s business and key ESG risks and opportunities.

Technology experience also continues to increase. In the S&P 500, the share of directors with such experience went up from 21 percent in 2021 to 25 percent in 2023. In the Russell 3000, it increased from 15 to 18 percent.

While many boards may not need directors who are “tech experts,” there is a widespread need for greater fluency in how technology affects the company’s business. In a recent survey of 600 C-Suite executives at US public companies, half of the respondents said their boards do not have a strong understanding of the impact of technology on their companies.

Rather than focus on narrow technology expertise, boards may wish to seek out directors who have experience at companies in adjacent industries that have undergone, or are undergoing, a technological transformation.

The decline in the percentage of directors with strategic experience is greater for new directors than for all directors. In the S&P 500, the percentage of new directors with such experience declined by 19 percentage points from 66 percent in 2018 to 47 percent in 2023. In the Russell 3000, it declined by 18 percentage points, from 65 to 47 percent. Moreover, compared to all directors, new directors are reporting higher levels of experience in environment/climate (12 percent of new S&P 500 directors and 6 percent of new Russell 3000 directors), ESG (15 and 11 percent), and human capital (38 and 24 percent).

Some of the decline in strategic experience may reflect the process that companies typically use to decide what skills and experience to disclose. The process generally begins with directors self-identifying their capabilities, based on a menu provided by the company. The company may also limit the number of areas that it will disclose for each director, sometimes as few as three or four. This can result in disclosures relating to new directors that emphasize experience in current hot-button areas, rather than core areas that are of equal, if not greater, importance. Based on our discussions with major institutional investors, this can expose directors as targets for shareholder activism, especially if investors are not familiar with those directors from other board or executive roles.

Strategic experience is most cited in directors at the largest and the smallest companies. As of August 2023, 66 percent of directors at the largest companies (with annual revenues of $50 billion and over) and 62 percent of directors at the smallest companies (with annual revenues under $100 million) reported having strategic experience—exceeding all other revenue categories.

Management in the largest and smallest companies may benefit the most from having directors with strategic experience. While all companies can benefit from a board with broad and deep experience in business strategy, the largest companies often face the most complex and multifaceted challenges due to their scale and scope, and the smallest companies with smaller internal strategic planning departments may routinely rely on the board for strategic advice.

Functional Background

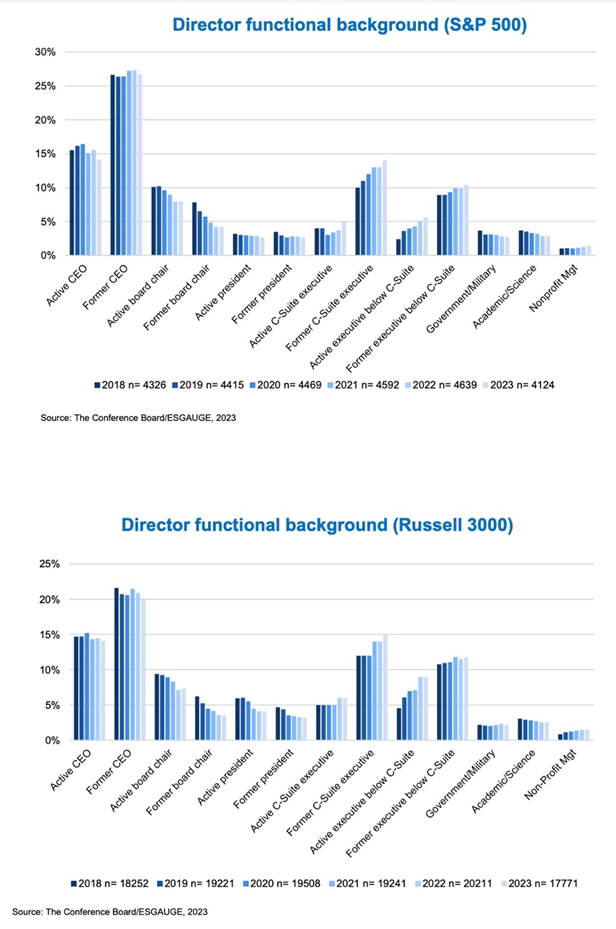

As boards look to diversify their composition, the percentage of directors who are active or former CEOs has decreased. The recorded decline was from 42 percent in 2018 to 41 percent in 2023 in the S&P 500, and from 37 to 34 percent in the Russell 3000. At the same time, the percentage of directors who are active/former C-Suite executives other than the CEO has increased from 14 percent in 2018 to 19 percent in 2023 in the S&P 500, and from 17 to 21 percent in the Russell 3000. Directors from a level below the C-Suite have also become more common, increasing from 11 to 16 percent in the S&P 500, and from 16 to 21 percent in the Russell 3000.

CEOs bring a unique breadth of experience to the board, but directors with C-Suite or near C-Suite-level experience can also provide advantages. They bring deeper experience in key disciplines (finance, human capital, legal/regulatory) as well as current experience and perspectives gained from what it means to work within, and not at the top, of an organization.

Company size correlates with the presence of directors with CEO backgrounds. Larger companies tend to have a higher proportion of CEO directors, whereas smaller companies typically have the smallest. As of August 2023, 47 percent of directors at the largest companies (with annual revenues of $50 billion and over) are current or former CEOs, compared to 30 percent at smaller companies (with annual revenues under $1 billion). Conversely, smaller companies are more likely to attract directors coming from a level below the C-Suite. Such directors make up 23 percent of boards at the smallest companies and 13 percent at the largest companies.

Larger companies often have more resources (and recognition and appeal) to attract and retain CEOs as board members. Rather than looking for CEOs, smaller companies may want to target C-Suite executives with strategic experience and broad business acumen and who have (or recently had) significant exposure to the board at their companies.

Retirement Policies Based on Age

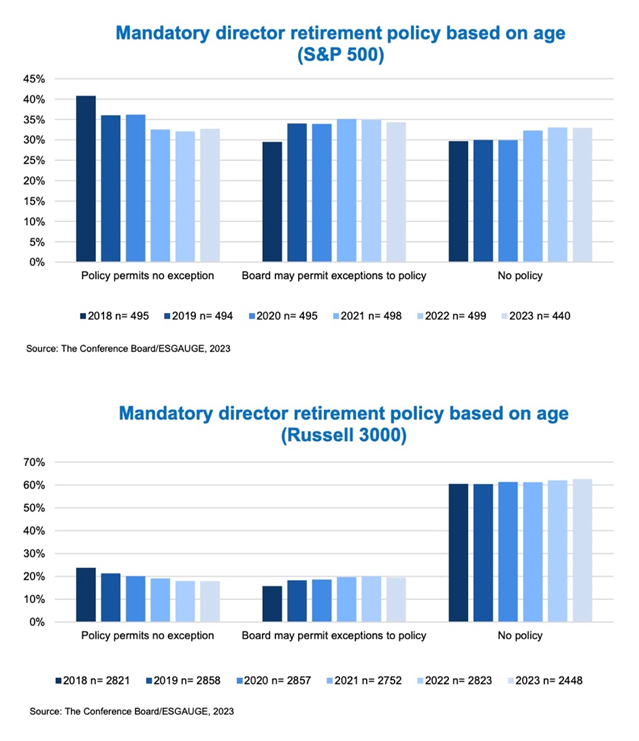

Larger companies continue to be much more likely than smaller firms to have a policy for mandatory retirement age that permits exceptions, while smaller companies are more likely to have no policy at all. One-third of S&P 500 companies have a mandatory retirement policy that allows no exceptions); 34 percent of S&P firms allow the board or nominating and governance committee to make exceptions to the retirement policy (down from 35 percent 2022); and 33 percent have no policy (the same as 2022). The approach to retirement policies at Russell 3000 companies is starkly different. Sixty-three percent of Russell 3000 companies do not have an age-based retirement policy (up from 62 percent in 2022). Just 18 percent of companies have a retirement policy that doesn’t allow exceptions, and 20 percent allow exceptions (no changes compared to 2022).

Just as smaller companies face a greater challenge in attracting CEOs to their boards, they may also be more concerned about their ability to replace directors who are required to leave because of an age-based retirement policy. At the same time, most “Big A” shareholder activism (which seeks to change the direction, board, or management of a company) is focused on smaller companies. Therefore, smaller firms—like their larger counterparts—may want to consider tools that at least encourage—rather than force—board refreshment, including mechanisms that prompt a discussion of turnover. A growing number of investors are explicitly requesting more robust board and director evaluation practices, in large part due to a desire to have boards rigorously assess whether each scarce board seat is being utilized most effectively. In addition to enhanced evaluation procedures, companies can also encourage refreshment with guidelines on average board tenure, policies requiring directors to submit their resignation upon a change in their primary professional occupation, and overboarding policies.

Despite the increase in the mandatory retirement age at companies that have such a policy, the average director age is holding steady. In the S&P 500, it has increased from 63.2 years in 2018 to 63.5 years in 2023, and in the Russell 3000, it went from 62.3 years in 2018 to 62 years in 2023. Not surprisingly, the average age for new directors continues to be lower than for all directors (58.2 years in the S&P 500 and 57 years in the Russell 3000).

Given the average age of new directors, they could conceivably serve on the board for nearly 20 years before reaching a mandatory retirement age. In both the interviewing and onboarding process for new directors, it can be helpful to set the expectation that the company’s goal is to have board composition that evolves over time to keep pace with the company’s and board’s needs with no expectation that directors will either serve until the mandatory retirement age or that their service will be ended because of a need to meet some arbitrary target.

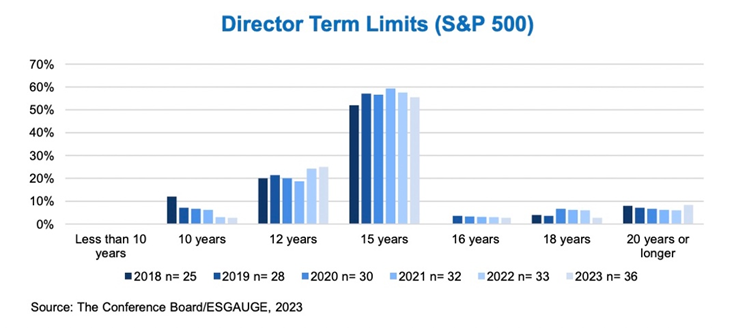

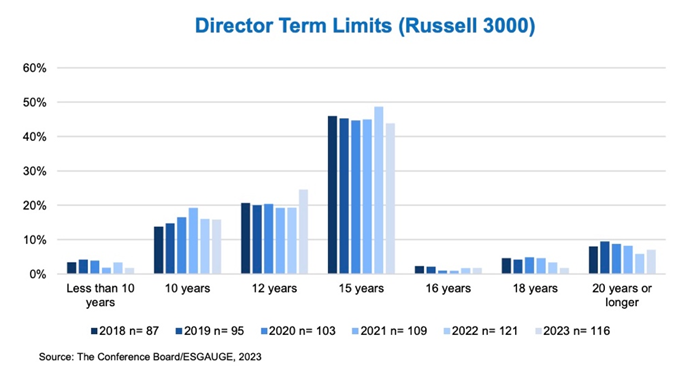

Term Limits

The percentage of companies establishing director term limits (mandatory retirement policies based on tenure) is growing, albeit very slowly, but it remains an uncommon practice as companies prefer to have flexibility to retain valuable directors. In the S&P 500, the share of companies with a retirement policy based on tenure grew from 5 percent in 2018 to 8 percent in 2023. In the Russell 3000, the percentage grew from 3 to 5 percent.

The largest firms are most likely to adopt term limits. Thirteen percent of companies with annual revenues of $50 billion and over disclose a policy that sets a maximum tenure. Conversely, only 0.4 percent of the smallest companies with annual revenues under $100 million have such a policy. This is consistent with large companies also having a stricter approach to age-based retirement policies.

The most prevalent term limit for companies that have a mandatory retirement policy based on tenure is 15 years, followed by 12 years. In the S&P 500, 56 percent of companies with such a policy require board members to step down after 15 years of service, and 25 percent set the term limit at 12 years. By comparison, 44 percent of Russell 3000 companies set the term limit at 15 years and 25 percent at 12 years.

Sitting director tenure is declining, which indicates that factors other than retirement are driving refreshment. In the S&P 500, sitting director tenure declined from 8.9 years in 2018 to 8.3 years in 2023. In the Russell 3000, the decline was even more pronounced, from 8.6 to 7.7 years. With the average mandatory retirement age increasing, the decline in sitting director tenure could be due to various factors other than retirement, including companies diversifying their board and adding new directors.

Departing director tenure is also declining. In the S&P 500, departing director tenure declined from 12.6 years in 2021 to 11.4 years in 2023. In the Russell 3000, it declined from 10.4 years in 2021 to 9.7 years in 2023. Given that most sitting directors were not serving on boards at times of prolonged economic uncertainty or geopolitical instability that are comparable to what we are experiencing today, it is important for boards to ensure that they have access to management and external resources that can supplement the board’s own experience. The need for boards to have a long-term perspective is applicable not only to the future but also to the past.

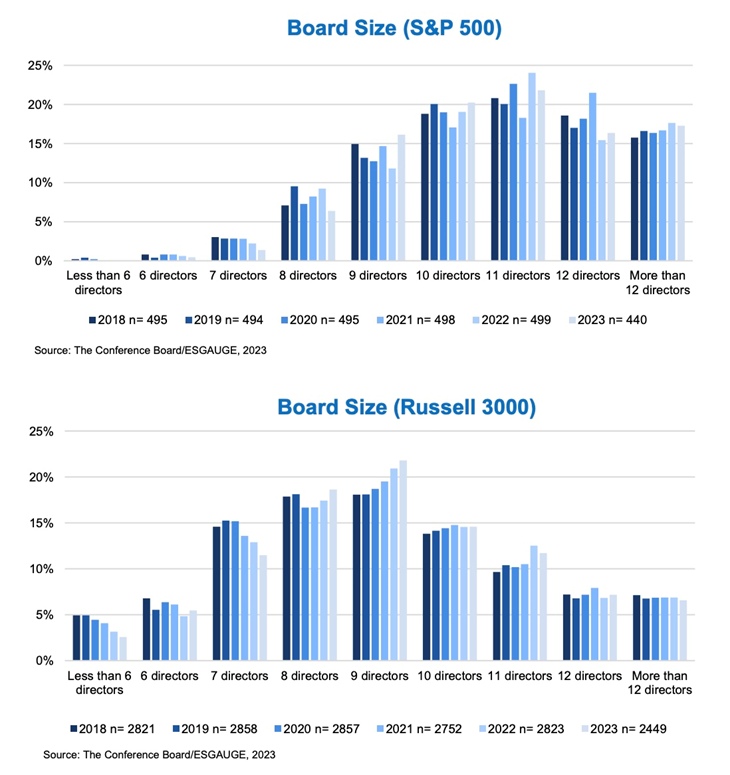

Average board size has barely increased in recent years, which is notable considering the ever-expanding range of topics that boards are expected to oversee as well as the growing demands to diversify the board room. In the S&P 500, average board size has stayed steady at 10.8 directors since 2018. In the Russell 3000, the average went up only slightly, from 9 directors in 2018 to 9.2 directors in 2023. There is a direct correlation between company size and board size, with the largest companies having the largest boards. For example, companies with annual revenues of $50 billion and over have an average board size of 11.4 directors. By comparison, companies with an annual revenue under $100 million have an average board size of 7.9 directors.

As board responsibilities grow, boards need to ensure that their size is—and will be—sufficient to accommodate the needed range of skills, experience, and perspectives without becoming unmanageable.

Despite a fast-changing operating environment, companies should take a long-term approach to board composition, ensuring that the board has critical core competencies for long-term performance regardless of the challenges of the day.

The following are our insights and recommendations to companies:

- Crucial director qualifications, such as business strategy experience, should not give way to or be underreported because of a focus on functional expertise in ESG and other areas, such as climate and cybersecurity. The reported percentage of directors with business strategy experience continues to decline, which may reflect both a shift in director recruitment and underreporting of core business experience—either put the company at risk for decreased board performance and increased shareholder activism.

- New directors, in particular, may become targets of shareholder activism. While activists have traditionally targeted longer-serving directors, new directors may now also be vulnerable. Activists usually highlight the relevant business background of their slate, which makes the stark decline in strategic experience among new directors an area of concern.

- To avoid being accused of “greenwashing” the board, companies should ensure that their directors’ self-disclosed qualifications can be substantiated. Amid increasing regulatory and investor pressure to demonstrate board fluency in specific areas, companies should validate that directors have significant—and preferably recent—experience in those areas.

- Board refreshment can benefit from long-term (and “depersonalized”) succession planning. Instead of recruiting directors only as vacancies arise, companies should look ahead several years for potential vacancies as well as the evolving needs of the company and the board. This can help both to “depersonalize” succession planning and ensure that the board is able to evolve to meet the company’s needs.

- CEOs may want to seek input from key members of the C-Suite when the board is recruiting new directors. A majority of surveyed CFOs, CLOs, and CHROs favor replacing two or more directors; CEOs should ask such key executives for their insights and where they may see gaps in expertise on the board.

- Companies should take a fresh look at their board size to ensure it allows for the needed range of experience, skills, and perspectives. As board responsibilities continue to grow over the long term, companies should ensure that the board strikes the right balance between diversity of experience and thought, and efficient decision-making—and consider modestly increasing their size, as appropriate, to meet this balance.

This report documents board composition and refreshment trends at US publicly traded companies—including information on independent director qualifications, skills, and professional backgrounds, and the use of retirement policies based on age and term limits to promote change in the board. The analysis is based on recently filed proxy statements and complemented by the review of organizational documents (including articles of incorporation, bylaws, corporate governance principles, board committee charters, and other corporate policies made available in the Investor Relations section of companies’ websites). The report also presents key insights gained during gained during a Focus Group discussion with in-house governance leaders.

Data discussed in this report can be accessed and visualized through an interactive online dashboard at conferenceboard.esgauge.org/boardpractices

Endnotes

1See Board Effectiveness: A Survey of the C-Suite, PwC/The Conference Board, May 18, 2023, p. 6.(go back)

2Company-size data in this report are not captured in the charts and apply to manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies. They exclude companies in the financial and real estate sectors as those tend to report on asset value instead of annual revenue. Our live, interactive online dashboard allows you to access and visualize practices and trends from 2018 to date by market index, business sector, and company size, including asset value.(go back)

[ad_2]

Source link