[ad_1]

Bernd Hofmann founded his engineering firm 56 years ago. He’s seen many ups and downs since then — the oil price shock of the 1970s, the upheaval of German reunification in 1990, the global financial crisis of 2008. But nothing like this.

“It’s one of the worst phases I’ve ever experienced,” the 80-year-old says.

Hofmann’s company Femeg, which makes water meters, safety valves and precision parts for the car and chemical industries, is the victim of a downturn that is raising serious doubts about the future of the country’s much-vaunted, export-led business model.

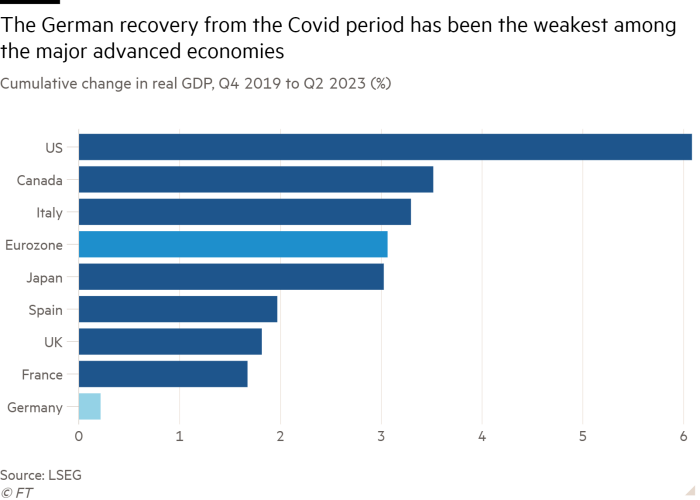

Germany’s economy is stuck in a rut. Its exports and manufacturing output are in decline, inflation is suppressing consumer demand and the construction industry is reeling from high interest rates.

Business leaders are sounding the alarm. Virtually “every European economy is growing, apart from Germany’s”, says Rainer Dulger, head of the BDA, the country’s main employers’ organisation. “That’s a clear signal we have to act.”

Indeed, the IMF predicted this month that Germany would be the worst-performing major economy this year, with GDP set to shrink by 0.5 per cent. It cited slower demand from its trading partners and weakness in sectors that are sensitive to high interest rates. In contrast, the US economy is forecast to grow by 2.1 per cent and France’s by 1.0 per cent.

Experts are clear on why Germany is facing such a uniquely grim outlook. It took a much bigger hit from last year’s surge in energy prices than many other large economies, partly because it has so many big gas-guzzling manufacturing firms. The ECB tightening monetary policy to tackle inflation has also taken its toll, as has a sluggish recovery in trade with China, Berlin’s biggest trading partner.

Robert Habeck, economy minister, admitted earlier this month that Germany was emerging from the crisis “more slowly than we expected”.

But some of the challenges the country faces are more long-term. Companies increasingly complain about the rising cost of doing business in Germany — the burden of climate policies, high taxes and expensive energy. They point to the dire shortage of skilled workers and excessive bureaucracy.

“We’re talking to the government about artificial intelligence and in their offices they still all have fax machines,” says Dulger. “It just doesn’t fit.”

Meanwhile the rise of electric vehicles — and China’s advances in the EV market in Europe — threaten an industry that was long a pillar of Germany’s economic success.

Nowhere is this process more evident than in the district of southwestern Germany where Femeg and a clutch of other medium-sized engineering companies are based. A recent survey by the think-tank IW Consult identified Donnersbergkreis, named after the eponymous mountain that dominates the surrounding landscape, as one of the most challenged regions in Germany.

The researchers looked at the two big transformations currently under way in the country: the shift to a carbon neutral economy, which will put pressure on energy-intensive and high carbon-emission industries such as steelmaking and chemicals; and the switch to electric cars.

They found that six of Germany’s 400 districts and towns would be particularly hit by these processes, and Donnersbergkreis was one of them.

For Bernd Hofmann, a reckoning is coming. “[The government] always told people here ‘we’re the best, the biggest, the greatest, and the sun will never set,” he says. “For years, the only way was up. And we fell into a kind of lethargy. [ . . .] The next few years are going to be tough for all manufacturers.”

‘All the lights will go out here.’

If there is a poster child for Donnersbergkreis’ economic woes, it is BorgWarner, a US-based car parts maker currently in the throes of a massive restructuring.

The company’s factory in Kirchheimbolanden, the regional centre of Donnersbergkreis, specialises in turbochargers, small turbines that force more air into a car engine’s combustion chamber to produce more power. It is the town’s biggest employer.

The company was long a market leader in the device. But demand has been declining for years, says Andreas Denne, head of BorgWarner Turbo Systems. The first blow was the Volkswagen emissions scandal of 2015, which, he says, caused a “collapse in the diesel market”. Then came the “whole discussion around electric cars”.

Initially BorgWarner hoped its prized gizmos still had a future; they could, after all, be deployed in so-called “mild hybrids”, which use a traditional combustion engine alongside a 48-volt battery. They also hoped conventional petrol and diesel engines might hold up for years to come.

The EU dashed those hopes with their decision to ban new vehicles with petrol and diesel engines by 2035. BorgWarner has since announced plans to cut the workforce at Kirchheimbolanden from about 1,600 in 2021 to 650 by 2028.

“For years we were used to growth, growth, growth,” says Denne. “From here we sent turbochargers out into the world. But times have changed, and anyone who has anything to do with combustion engines is affected.”

So are all the local companies that supply BorgWarner. Our “historical fixation on turbochargers” is a “major challenge,” says Rainer Guth, head of the Donnersbergkreis district council. Take Femeg: providing parts for the devices made up 80 per cent of its automotive business.

Other nearby companies, too, are oriented to the auto industry. One is Gienanth, a big iron producer established in 1735 in Eisenberg, the biggest town in Donnersbergkreis, which found early fame a century ago by making parts for Bugatti racing cars.

It now produces components for locomotive and ship engines, and for the emergency generators used in hospitals or data centres. It also makes brake callipers for commercial vehicles and crankshaft bearing caps for BMW engines — a side of the business that will inevitably be affected by the phaseout of combustion engines.

Gienanth says it has spent the past few years “collaborating with customers on product solutions for EVs”. It is also “expanding and diversifying its product portfolio”, for example by working with the Berlin start-up STUR on making cast iron saucepans.

Donnersbergkreis is not a grimy relic of Germany’s fossil-fuel past. The region is plastered with wind turbines and solar panels. It boasts a Japanese-owned factory that makes surveillance cameras. Just beyond its borders lies the city of Kaiserslautern, where Automotive Cells Co, a joint venture between Mercedes-Benz, Stellantis and TotalEnergies, is building a gigafactory to produce lithium-ion battery cells for EVs.

But while some parts of the region are reviving, others are in decline. An hour’s drive away from Donnersbergkreis lies Saarlouis, home to a big Ford factory with a near-60 year history — and a bleak future.

Ford said last year it would stop building cars at the plant and construct its next generation EVs in the Spanish city of Valencia instead. This month it announced that talks to sell the factory to a big unnamed investor had failed. More than 3,000 jobs are at risk.

The slow demise of petrol-powered cars is one issue facing Donnersbergkreis; the huge surge in energy costs another. Reiner Bauer, the district’s head of business development, says many of the region’s energy-intensive companies were long seen as “innovative, profitable, with model training programmes and excellent management”. But the energy crisis changed all that.

“When you’re facing spiralling energy costs, you’re just no longer competitive internationally,” he says.

He cites the example of Heger, an iron foundry near Kaiserslautern making parts for wind turbines. The company declared insolvency in September last year: it said it was paying €700,000 a month for electricity, up from €100,000 before the price surge, and could no longer pass that increase on to customers. “The energy prices are killing us,” Johannes Heger, managing director, told local media at the time.

Another company paying a lot more for energy these days is BASF, the world’s biggest chemicals group, which is a 40-minute drive away from Donnersbergkreis in Ludwigshafen, on the Rhine. It has been forced to shut down several of its most energy-intensive production lines, including for ammonia, cyclohexanol, which is an ingredient of soaps and plastics, and TDI, used to make foam mattresses. Some 700 jobs will be affected.

The government is fatalistic about such developments. “We only produced ammonia here because we had access to cheap Russian gas — and now that’s gone,” says one senior official. “I don’t think Germany will be manufacturing basic chemicals, plastics and ammonia in 2035. Maybe it just makes more sense to produce them in Saudi Arabia, where energy is cheaper.”

But that’s not how it is seen in Donnersbergkreis. The district is home to hundreds of commuting BASF workers, who have watched in alarm as the company builds a new €10bn petrochemicals plant in China and downsizes in Europe.

“If such a company were to shift operations abroad because of high energy costs or a shortage of skilled workers in Germany, all the lights will go out here,” says Guth.

Building problems

It’s not just energy-intensive industries that are suffering: the slump in Germany’s construction sector is also being felt in Donnersbergkreis. “The situation is dramatic,” says Frank Dexheimer, head of Frambach, a building company in Kirchheimbolanden.

Construction firms across Germany have been hammered by high interest rates and a big increase in the cost of building materials. A survey by the Ifo Institute, a think-tank, found 21.4 per cent of residential builders were affected by project cancellations in September, the highest level since records began in 1991.

Dexheimer’s firm has been cushioned by the diversity of its services. It is involved in civil engineering projects and residential building renovations, where contracts are still to be had. But all companies focused solely on new construction are suffering, he says.

“Next year is going to be cruel for those guys,” he adds. “We’ll see lots of insolvencies.”

The real victims of the crisis are young families, Dexheimer says. The pricetag for a one-family house with a plot of land in Donnersbergkreis was €500,000 a couple of years ago, he says; now it is €750,000, the result of higher building costs. Meanwhile, mortgage rates have risen from about 1 to 4–5 per cent.

“Young families can’t get a home loan any more — they’re just too expensive,” he says.

Evidence of the slump is easy to find in Kirchheimbolanden. The town recently tried to market about 40 building plots for new houses, but only managed to sell three of them. “The site is lying idle,” says Dexheimer. “Demand has collapsed.”

Donnersbergkreis is also prey to one of Germany’s most abiding problems: a chronic shortage of skilled labour. The government has said that an ageing population means Germany could lack 7mn workers by 2035. It has passed laws to make it easier for foreigners to take up a job in the country. But business groups say much more needs to be done.

Hubert Hack, owner of a small iron foundry in Eisenberg that makes parts for the auto and mechanical engineering industries, says that finding workers has become his “biggest challenge” — even larger than high energy bills. He has been trying to fill three vacancies at his company for months.

“Young people seem more concerned about their work-life balance than with working hard,” he says.

Hack says he has resorted to hiring pensioners. “I have five of them that work here part-time, as needed,” the 64-year-old says. “They’re more reliable than the young.”

His story is typical. An Ifo survey in August found 43.1 per cent of German companies lack skilled workers. Habeck admitted earlier this month that the issue was one of the “biggest structural challenges we have to overcome.”

‘We need to get our mojo back’

But Habeck also sees reasons to be hopeful. Speaking to reporters earlier this month, he said the German economy should return to growth next year. Inflation is declining, the labour market is robust and real incomes are rising, he said, which could help to drag domestic demand out of its slump.

That optimism is shared by Joachim Nagel, head of Germany’s central bank. Speaking to business and political leaders in Berlin last week he dismissed claims Germany was the “sick man of Europe” or a country in the grip of “deindustrialisation.”

German companies had weathered the gas crisis well, he said, investing heavily in efficiency measures to cut their energy use. They had shown themselves to be “highly adaptable”, he said, praising the ingenuity of the country’s “hidden champions” and the strength of the Mittelstand, the small and medium-sized companies that form the backbone of the German economy.

Their resilience had left him “generally optimistic,” he said. “‘Made in Germany’ will, in my view, continue to be a coveted and successful trademark.”

Longer-term, Germany is also making great strides in building up new industries. Lured by massive subsidies, Intel and TSMC are constructing semiconductor plants in Magdeburg and Dresden, representing a shift in Germany’s industrial geography from the south to the east. Battery factories for electric vehicles are springing up everywhere and old-established companies such as Thyssenkrupp are investing billions to decarbonise their production.

Habeck says his ministry is overseeing an €80bn pipeline of planned investments by foreign firms. “Germany as a location for business is strong if it wants to be,” he said last month.

BorgWarner, the automotive turbine maker, is trying hard to reinvent itself. It has developed an “eBooster”, an electrically driven compressor that can be used in hybrids. Denne describes it as a “bridge to the future” for the Kirchheimbolanden site.

The company is also looking to use its turbocharger technology for decentralised power generation. Its Kirchheimbolanden tech centre has developed an “e-fan” — an electrically-driven fan for cooling the components of battery-driven cars. But that will be manufactured at BorgWarner’s factories in Portugal and the US, not in Donnersbergkreis.

Hans-Joachim Retzlaff, head of human resources at the tech centre, says business opportunities for the German auto industry are set to shrink.

“If you look at how Germany is turning into an importer of electric cars, and that we should reckon with lots of cheap Chinese EVs, it’s clear our share of the global market will dwindle,” he says. “And our business will become correspondingly smaller.”

Femeg is also trying to move with the times, away from the automotive sector and into arms manufacturing, an area that has boomed in Germany since the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

It owns a foundry in south-western Germany that makes components for Leopard tank engines and is also shifting to producing munition and parts for heavy military equipment.

“We’re not just sitting here moaning, you have to keep moving,” says Bernd Hofmann. But he thinks the downturn will deepen unless the government takes more decisive action, in particular on the question of energy costs.

“We have to make this country a more attractive place to invest in again,” he says. “We need a new spirit of optimism. We need to get our mojo back.”

Additional reporting by Martin Arnold

[ad_2]

Source link