[ad_1]

A Native American teenager who died while attending a Utah boarding school for at-risk youth had been sick in the weeks beforehand, but staff had been trained to assume students would lie about being ill and did not try to bring her to the hospital until the day she died, former staff members said in interviews.

Taylor Goodridge, 17, collapsed at Diamond Ranch Academy in Hurricane, Utah, on Dec. 20. While an official cause of death has not yet been determined, her family said in a lawsuit that they believe she died of sepsis, a life-threatening condition that arises from a body’s response to infection.

The Utah Department of Health and Human Services placed Diamond Ranch Academy’s license on “conditional status,” allowing it to remain open while the agency and the Hurricane Police Department investigate Taylor’s death. The Health and Human Services Department said the academy is “actively collaborating with investigators.”

Dean Goodridge, Taylor’s father, sued Diamond Ranch Academy in federal court on Dec. 30, alleging that the school knew his daughter was severely ill but told her to “suck it up” and take aspirin.

An attorney for Diamond Ranch said the facility has “substantial disagreement with many aspects” of the lawsuit and allegations by former staff, but could not respond in detail because of federal privacy law governing education and medical records.

“One thing we have agreement on, it’s a tragic circumstance,” said Bill Frazier, the school’s attorney. “Any time you have a 17-year-old die, it’s horrendous and we’re crestfallen by it.”

NBC News spoke to seven former staff members of Diamond Ranch Academy, including five who said Taylor was ill on different occasions in the three months before her death but was not taken off campus to be evaluated. Four spoke on the condition of anonymity because they fear retaliation by the academy’s leadership. Their accounts echoed the claims made in Goodridge’s lawsuit.

“There would be nights she would throw up and staff didn’t care to do anything,” said Tianamarie Govan, who supervised girls during night shifts at Diamond Ranch Academy until Oct. 20, adding that Taylor was complaining of severe stomach and lower back pains at that time. “There were times I’d have to stay in her room to make sure she was OK. She had a really high fever one night, but the [supervisory] staff refused to allow me to use a thermometer to check it.”

Matt Thomas, who was a youth mentor at Diamond Ranch Academy until late December, said that he read a Dec. 19 staff memo that stated Taylor was so sick she did not want to go to lunch.

Facility records shared with NBC News by a former employee show that Taylor had vomited on at least three days in the week leading up to her death.

Another former staff member, who quit Diamond Ranch Academy in December, said that Taylor was vomiting multiple times a day and complaining of extreme stomach pain before she died. She looked pale and had a swollen stomach, the former staff member said.

“She wouldn’t be able to walk up to medical without help,” the former staff member said, referring to the office where staff medical professionals worked. “We’d have to carry her arms to get over there. It was really bad, and they didn’t do much for her besides giving her Gatorade powder.”

The seven former staff members all told NBC News that Diamond Ranch Academy management warned them that children who complained about feeling sick often did so to get attention, avoid homework or convince their parents to remove them. Only medical staff could recommend that a child be taken to a hospital, but to do so generally would have required a staff member to leave campus, putting them out of sync with state-mandated ratios of adults to children, the former staff members said.

If children objected, they couldn’t tell their families because the school controlled who they could call, and limited and monitored their phone calls and letters with parents, the former staff members said.

“They’re trapped when they have a medical issue,” said Alan Mortensen, an attorney for the Goodridge family. “It’s not like if they disagree with what the staff is telling them that they can just walk out the door and go to the doctor, or even call their parents to take them to the doctor. It’s totally to the discretion of the school.”

Frazier, Diamond Ranch Academy’s lawyer, said many of the allegations from former staff and the family’s lawsuit are “demonstrably false,” but the school declined to share more details due to the ongoing litigation and investigations. “DRA will continue to fully and transparently cooperate with all appropriate agencies,” he added. “DRA looks forward to presenting the facts in court.”

Accusations of mistreatment in youth facilities

Dean Goodridge said he last saw his daughter during a visit on Nov. 16 and she seemed fine. He said she did not complain during weekly webcam calls he had with her and her therapist, but a week before she died, Diamond Ranch Academy canceled their call because she was sick. They had been scheduled to see each other in person on Dec. 21.

“But then we get the phone call,” he said.

He said the academy told him on Dec. 20 that Taylor had died of a heart attack after passing out in the school parking lot when they were about to take her to the hospital.

The next day at a meeting for staff, according to audio obtained by NBC News, a supervisor told employees that Taylor had died of an illness.

“She seemed like she was getting better,” the supervisor said. “Around 4, 4:30 yesterday she got worse and we decided to take her to the E.R. She lost consciousness before getting to the van.” Then they called 911, he said, and paramedics revived her but she lost consciousness again at the hospital.

“Unfortunately this wasn’t the first time I had to deal with this,” the supervisor said, “and it probably won’t be the last, depending on how long I stay here.”

When Thomas, a nightwatch staff member, asked why it had taken more than a day to inform employees of the death, the supervisor quickly cut him off and told him to leave the meeting, according to the audio. Thomas was fired a few days later in a text message, shared with NBC News, that cited his “conduct during our department meeting.” (Frazier said the school had “ongoing challenges” with Thomas leading to his termination, but declined to discuss further.)

Another former staff member, who had quit before Taylor’s death, said that in the days that followed, a Diamond Ranch Academy administrator called them to make sure “the facts are correct for everybody.” That account included that staff had been checking Taylor’s vitals every hour, and Taylor seemed to be fine until she collapsed, and the school had done everything it could to care for her, the former staff member said.

Do you have a story to share with NBC News? Email reporter Tyler Kingkade

Taylor’s death has prompted alarm among children’s rights advocates and lawmakers who are calling for increased oversight and tougher penalties for troubled teen institutions, private facilities that promise to help adolescents who misbehave or struggle with emotional issues.

“These facilities are really good at telling mom and dad, you know, ‘Everything’s under control, you’ve got to trust us that we know what we’re doing,’” said state Sen. Mike McKell, a Republican who sponsored the legislation. “And I think there’s definitely been examples where it’s families that have been manipulated.”

Taylor is the third child to die in a residential treatment facility’s care in Utah since the state enacted a set of reforms in March 2021, including outlawing certain physical restraints and guaranteeing children a right to communicate with their parents. McKell and youth rights advocates think the state needs to do more to ensure children’s safety within the nearly 100 troubled teen institutions in Utah.

“It’s all just in reaction,” said Meg Applegate, CEO of Unsilenced, a children’s rights advocacy group that closely monitors the licensing of troubled teen facilities in Utah. “And it’s only after that one incident, and then it doesn’t take into account the entire history of that facility.”

The state Department of Health and Human Services said in a statement that its staff conducts announced and unannounced inspections of facilities to identify problems and increase monitoring of programs when warranted.

“If we determine the provider is taking the appropriate action to come into compliance with rules, our job is not to close them but to support their efforts to become better providers, as long as the health and safety of their clients are not compromised,” said Katie England, a department spokeswoman. “We want to make sure all Utah licensed providers are giving the highest level of care and ensuring safety of those in services, and we work to make sure revocation and closure are a last resort.”

Taylor’s death is the latest in a yearslong record of grim incidents and allegations at Diamond Ranch Academy, including the death of at least two other children at the school; a school nurse who forged opioid prescriptions; a teacher convicted of possessing child pornography; and lawsuits accusing staff members of inappropriate behavior with students.

James Shirey Jr., 14, died of complications from congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a genetic disorder, while at Diamond Ranch Academy in 2009.

In 2013, according to a lawsuit, the academy left a suicidal 16-year-old boy unsupervised, he tried to hang himself, and staff members did not get him down for nearly three minutes. The boy died two days later as a result of his injuries. Diamond Ranch Academy disputed some of the lawsuit’s allegations in a court filing, and denied wrongdoing, but paid his family a $750,000 settlement in 2017.

In 2016, according to another lawsuit, a male therapist sexually abused a 16-year-old girl, and staff pressured her to recant after she reported the incident to police. Diamond Ranch Academy and the therapist both disputed the allegations, and the therapist countersued the girl and her family for defamation (they denied wrongdoing as well). Both suits were dismissed following an out-of-court agreement.

Another suit filed in 2021 alleged that a group of staff members restrained a 15-year-old girl on the ground with enough pressure to cause partial facial paralysis. The school responded in court that restraints are only used when a child is a threat to themselves or others. The case is ongoing.

Diamond Ranch Academy declined to comment on previous lawsuits and deaths.

Amber Wigtion, Taylor’s mother, who is not part of the lawsuit, said she wants the school to close.

“No student there deserves to be treated the way my daughter was treated or any other student before her,” she said in an email. “As I dig deeper into that school, it is horror story after horror story, and it breaks my heart to hear that so many have endured such horrible actions by the staff there.”

Breaking Code Silence and Unsilenced, two activist groups that worked with Paris Hilton to advance Utah’s reform law, have called on the state government to evaluate whether to let Diamond Ranch Academy maintain its license based on its entire history, not just the circumstances of Taylor’s death.

“We can’t keep moving on,” said Applegate, of Unsilenced.

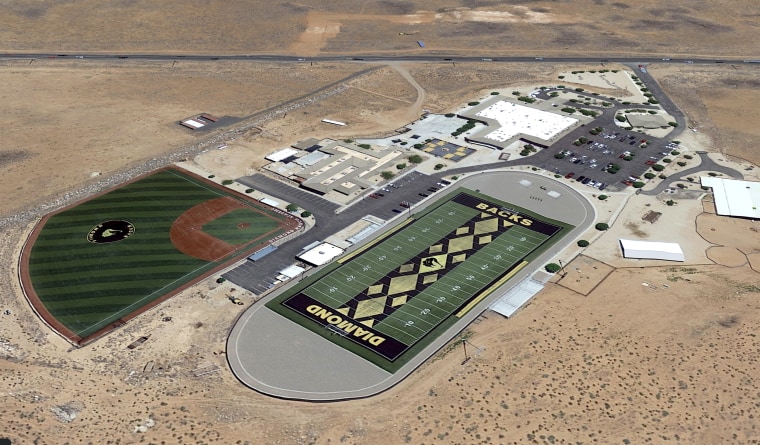

Diamond Ranch Academy was founded in 1999 by Rob and Sherri Dias. Their son, Ricky, is the executive director. It obtained accreditation from the Joint Commission, an influential nonprofit organization that evaluates health care facilities, in 2021. The facility, which had about 150 children enrolled as of last year, according to a former staff member, charges about $12,000 a month to attend.

According to former staff members as well as job listings, many of the workers who care for the children are hired at $13 an hour, with slightly higher rates for weekends or overtime shifts. Turnover is high, former employees said, and they were frequently short-staffed.

Taylor was a member of the Stillaguamish Tribe in Washington who went to Diamond Ranch Academy in October 2021 at the recommendation of a counselor to address emotional issues.

Former staff members who worked with her said she was the first person to make new girls feel welcome and constantly wrote in her journal. Her family said she liked makeup, volleyball, cheerleading and the Disney characters Lilo and Stitch. She had a sweet tooth, loved any animal she could pick up and dreamed of becoming a veterinarian. She had two young nieces — one was almost 3, the other almost 1 — and she died before meeting the youngest one.

She was not the type of teen to needlessly complain or exaggerate illness, according to former staff members. In the week before she died, two former lower-level staff members said they and other employees asked if the school should take Taylor to a hospital, because she had been in and out of the bathroom and had trouble sleeping. “We were shut down by the higher-ups,” one of them said.

“I didn’t have the nurse’s email or phone number,” said another former staff member, who also noticed Taylor was sick in the weeks before her death. “They had a serious lack of staff information and they weren’t transparent about each student’s medical condition or why they were there.”

A lawsuit filed by four former students against Diamond Ranch Academy in 2014 alleged that students who said they were sick were accused of being “manipulating” and refused treatment and that one child who attempted suicide was not taken to a hospital. (The suit was dismissed on technical grounds before the facility responded to the allegations.)

“When they train you, they tell you, ‘A girl will do anything to get out of here, they’ll throw you under the bus,’” said Leslie Walker, who worked at the academy as a program director until mid-October.

Family members buried Taylor in Stanwood, Washington, on Jan. 12.

Dean Goodridge wants to see accountability for Diamond Ranch Academy, and any other facilities where children have died.

“They don’t need to exist,” he said. “Because children don’t need to be treated like that. They’re not a paycheck. They’re a person. They’re a human being. They’re somebody’s child.”

[ad_2]

Source link